As a new publication celebrating the pioneering dancer's work is released, AnOther highlights ten things you might not know about his extraordinary life

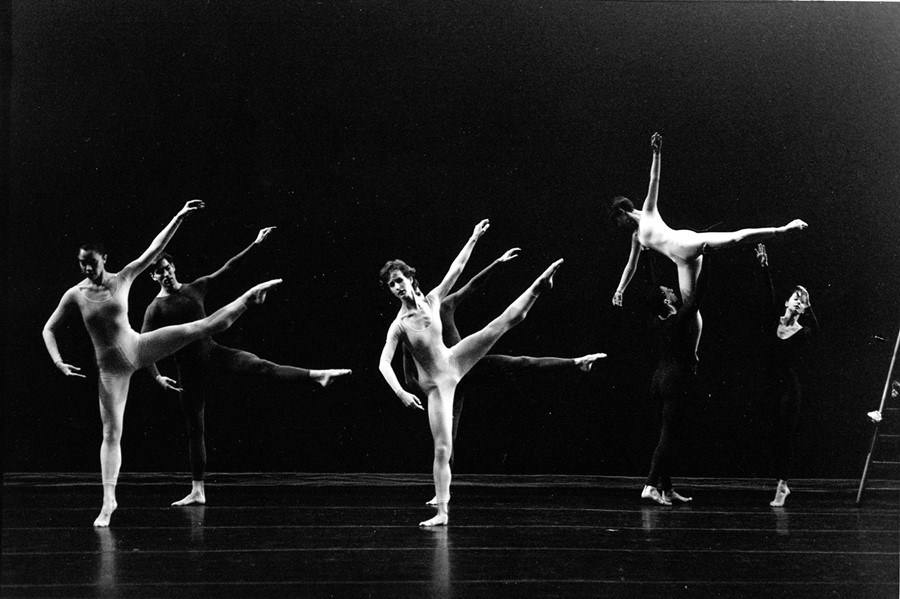

“Dancing is a spiritual exercise in a physical form,” Merce Cunningham once stated, and indeed, in his hands, it was often elevated to a higher plane. Cunningham spent more than 60 years working at the very forefront of modern dance and choreography, developing innovative techniques and collaborating with such powerful figures as to ensure his impact will never be forgotten. "Merce Cunningham changed the way people dance and the way people see dancing in the same way that Picasso and the Cubists changed the way people painted and the way people see painting," publisher Damiani explains. "He took dance apart and put it back together again, leaving out all but the most essential." As a new book of photographs by Stephanie Berger is released, entitled Merce Cunningham: Beyond the Perfect Stage, we consider some of his most influential contributions to the medium, and lesser-known facts about his life.

1. His first teacher moonlighted as a circus performer

Cunningham’s first encounter with dance came via an early teacher, Mrs Maude Barrett, a circus performer and vaudevillian whose infectious energy motivated the young visionary from an early age. "I started as a tap dancer," he told the Los Angeles Times of his origins. "It was my first theatre experience, and it has stayed with me all my life."

2. He counted Martha Graham as one of his key influences

American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham had an extraordinary influence on the evolution of the visual arts scene during the early 20th century – her eponymous technique fundamentally changed the way dance was taught around the world – so it makes sense that she came to represent a significant figure for Cunningham too. His enduring awe of her came full circle in 1939 when, on seeing him dance at the Cornish School in Seattle, Graham invited Cunningham to move to New York and join her company, where he spent six years dancing as a soloist.

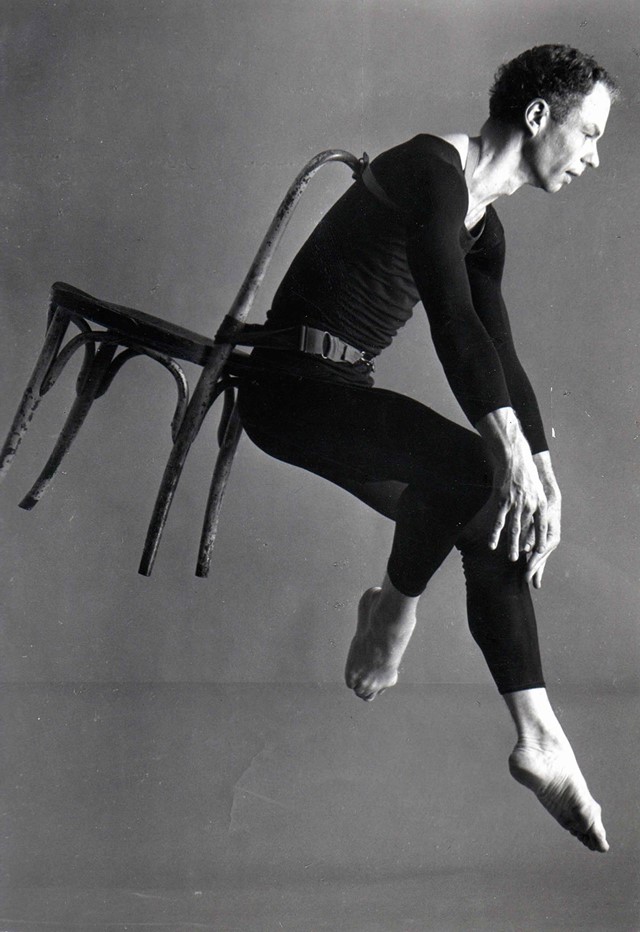

3. He was a great ‘leaper’

Cunningham’s outlook was characterised by his belief that the possibilities of the human body are limitless – and, indeed, his own body seemed almost immune to the effects of gravity, his powerful leaps becoming one of his most defining features as a dancer.

4. His eponymous company was formed while teaching at Black Mountain College

North Carolina’s Black Mountain College was a pioneering entity in its own right – it was opened in 1933, in part to provide a safe space for avant-garde artists fleeing the oppression of Nazism in Germany and across Europe, and went on to become one of the most groundbreaking educational establishments the US would ever see. Thus, its profound influence on Cunningham, who spent a summer there as part of the teaching residency in 1953, is unsurprising. It was while working at the college, and seeing its revolutionary and liberal approach in allowing students to balance their own curriculum, that he decided to start his own company.

5. He was a passionate advocate of collaboration

Collaboration was one of Cunningham’s primary motivations, and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company provided him with the perfect opportunity to work with some of the greatest creative thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries. From taking on visual artists as resident designers or artistic advisors – Robert Rauschenberg held the first of these posts from 1954 to 1964, and Jasper Johns the second from 1967 to 1980 – or collaborating on singular projects with some of the most innovative names of the moment – take Rei Kawakubo, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, for example – he was to instil partnership into the very core of his practice. Over the course of the company’s 58-year tenure, it commissioned more work from contemporary composers than any other, including Radiohead, Sigur Ros and Sonic Youth.

6. Musician John Cage was his lifelong partner

When Cunningham met American composer John Cage at the Cornish School in Seattle in 1938, the two immediately embarked upon an intense and enduring artistic collaboration, which was to last for the rest of their lives. They are widely believed to have been partners in love, as well as in work, although both were reluctant to confirm this verbally; when asked to describe his relationship with Cunningham, Cage’s cheeky retort was ambiguous: "I cook and Merce does the dishes."

Their romantic rapport was ostensibly the least interesting thing about the pair, however: far more fascinating are the many collaborative discoveries they made about the interplay between music and dance, which, unusually, they believed did not need to be linked at all. "I remember so clearly the first day when we were rehearsing with John and I made a large, strong movement,” Cunningham once said. “There was no sound, but just about three seconds later came this ravishing sound, and it was very clear that this was a different way to act: not being dependent upon the music but equal to it. You could be free and precise at the same time." He later added, "It is hard for many people to accept that dancing has nothing in common with music other than time and the division of time."

7. He was a great believer in the power of chance

The I Ching, or the Book of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination text which was to become enormously influential on Cunningham’s performances: he often used it to determine the sequence his pieces would take, and would refrain from informing the dancers performing it until the last possible moment. This was precisely the culture of flexibility and spontaneity he enforced upon his dancers. As composer Morton Feldman describes it, "suppose your daughter is getting married and her wedding dress won't be ready until the morning of the wedding, but it's by Dior."

8. His work focused on the 'moment'

Cunningham famously shied away from creating dances which depicted a historical narrative or event, instead opting to create non-representational choreography which defied traditional techniques. Most importantly of all, he was fuelled by his love of the form itself. “You have to love dancing to stick to it,” he once said. “It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed and sold – nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive."

9. He was one of the first to implement technology in his creative process

Cunningham was relatively early in his embrace of technology to advance the possibilities of dance, and in the 1990s he began to implicate computer animation in his choreography process, rather than relying solely on physical rehearsal. "The computer allows you to make phrases of movements,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “Then you can look at them and repeat them, over and over, in a way that you can't ask dancers to do, because they get tired." By 2009 he had taken this to a new level once again, debuting a computer programme which incorporated computer-generated imagery into live performances, not long after his 80th birthday.

10. His company chose not to carry on without him

Cunningham died peacefully at home in Manhattan in July 2009, and his company, unable to bear the prospect of continuing without him, launched a two-year farewell tour. They visited more than 50 destinations over the course of the grand goodbye, before closing forever with one final performance in New York on December 31, 2011.

Merce Cunningham: Beyond the Perfect Stage by Stephanie Berger is out now, published by Damiani.