As their newest public installation opens in NY, the interdisciplinary masterminds behind Prada Marfa talk to AnOther about building walls to break down boundaries

Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset have been challenging staid ways of contemplating art and its institutions, society and its systems, for over two decades. Employing sculpture, installation, performance and architecture, their collaborative art practice confronts dogma and habituality through subversive agitation. Though based in Berlin, the Scandinavian-born duo has dotted the globe with their compelling public works, such as Prada Marfa, a fake boutique sat in the Texan desert. Their latest public installation, an ear-shaped swimming pool cast in Van Gogh’s memory, is unveiled in New York this week.

But it’s at their exhibitions that their critiques ring loudest. For Self-Portraits, Victoria Miro (2015), they filled the space with renderings of labels designating other artists’ pieces, opening a dialogue about self-representation in contemporary culture. Their internationally acclaimed The Welfare show (2006) turned the Serpentine Gallery into a forum for the discussion of declining welfare states and neoliberal policies; whilst their current Well Fair show at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, sees the gallery transformed into a fictional art fair inviting questioning of the art market and its participants.

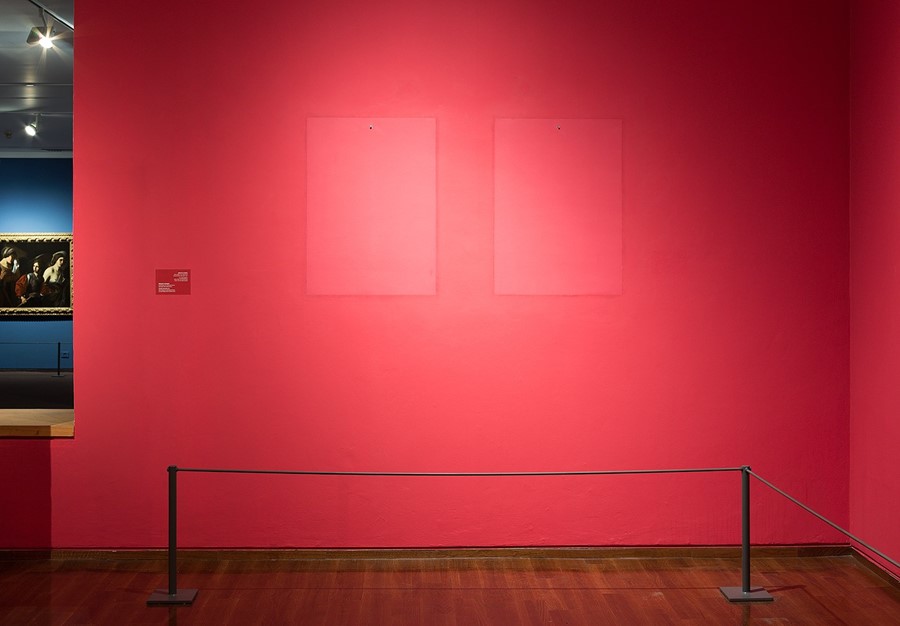

The pair's Powerless Structures series, ongoing since 2009, was inspired by a misreading of Foucault, and wills attendees to view structures anointed “powerful” as mutable human creations devoid of true force. And it’s this strand which they are presently continuing at Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Their un-labelled works, some new and site-specific, including a vast replica of a section of the Berlin Wall, (For As Long As It Lasts, 2016) and falsified signage for an imaginary Matisse show (Other Landscapes, 2016); some previously exhibited such as Donation Box (2006) are spread throughout the museum in a “broken trajectory”, inviting uncertainty into the experience. For as Elmgreen & Dragset say, “We don’t want to dictate people's behaviour. They should start reflecting as they meet our works.”

On the reasoning behind their art…

"If there's one thing we do art for, it's for people to feel less fear. If people feel fear in societies you can manipulate them and they can turn incredibly conservative and do horrible things. If we, with our small, silly interventions can make people a little less afraid then we are happy."

On spacing works throughout the museum…

"It was partly to invite people to visit others areas and also so that our pieces became less “artworks”. We have a piece called Modern Moses (2006), a baby under a cash machine, which functions better here as it's out of an art context in a hallway. People don't think it's weird to have a cash machine in a gallery, but they are upset about the baby. The guards get requests to do something about it about ten times a day so that works well."

On installing a replica of part of the Berlin Wall…

"It’s partly a biographical work as its fall drew us to Berlin in the early 90s and made its art scene international. So it’s an example of how tearing down a wall can cause a city to flourish and open a dialogue with the rest of the world. And it's also a work about walls in general, not only the wall between Palestine and Israel, but Donald Trump’s proposed border walls, and new fences suddenly going up within Europe. But the good thing is that they won’t last forever. This idea of politicians’ that you can avoid a problem if you build a structure is shortsighted."

On the weakening of social bonds…

"When we staged The Welfare Show in the Serpentine we were already speaking about individualism taking over so instead of feeling you have an identity according to class, sexual orientation, interests or community, it’s increasingly about your personal opportunities; not thinking about your neighbour or being a good citizen, which sounds old school but you can't have societies where we’re all completely egomaniacal. We need a sense of belonging, collaboration and togetherness, otherwise we end up in crazy anarchy."

On narcissism…

"Selfie culture is in itself quite innocent but it’s also a symptom of something a bit sick: this belief that the world does not exist if your smiling face is not in front of it. If you had glimpsed this scenario, even ten years ago, you would have said, ‘what the fuck is going on with all these people taking photos of themselves?’ Being able to flip the cellphone camera has made us narcissistic."

On cultural boycotts…

"They are a very bad thing, as you boycott those in the community who are progressive or like-minded and miss an opportunity to speak out in a place like Israel which doesn’t currently have direct censorship. I would find it ridiculous to boycott Tel Aviv Museum as the staff try to instigate change, give Palestinian artists opportunities and share new perspectives on social matters. Suzanne Landau, the gallery’s director, is progressive and critical of local policies, which is important for the contemporary art scene, especially as the new minister of the cultural affairs used to be in charge of censorship. We thought it was important to support positive endeavours within the city and create something that would relate."