As the ICA presents young Chinese artist Guan Xiao’s first solo exhibit in London, we enter her idiosyncratic world, in which ancient artefacts meet digital debris

Who? You can always rely on London’s ICA to provide a blueprint of contemporary artists to keep an eye on. True to form, in association with the equally forward-thinking, Hong Kong-based art foundation K11, the Institute is currently playing host to Flattened Metal, an exhibit by swift-to-rise Beijing-based video artist and sculptor Guan Xiao. At the frontline of a new generation of Chinese artists, Xiao seeks to forge a global visual language that breaks free from the shackles of cultural specificity. As ICA Head of Programme Katherine Stout elucidates, Xiao approaches her practice “in quite different ways to that of earlier generations of Chinese artists, and (thinks of herself) as working within an international art scene, responding to concerns and interests that are shared globally as much as they are influenced by their local context”.

Such an approach seems to be serving Xiao well. Since Art Review Asia included her in their annual Future Greats issue (2014), among numerous other exhibitions, Xiao’s artwork has appeared in the 13th Biennale de Lyon: La vie moderne; the New Museum’s 2015 Triennial: Surround Audience; Rare Earth at Vienna’s Thyssen-Bornemisza; and is currently mingling among Pierre Huyghe, Ed Fornieles, Neil Beloufa, et al. at the Zabludowicz’s group show Emotional Supply Chains. Listing these exhibits is significant, not merely to suggest Xiao’s international stature, but also, because they all share a common interest in our modern-day experience of temporal, emotional, physical and digital uncertainty – concerns that all guide Xiao’s practice. “The complexity and indeed playfulness in which she explores her ideas, objects and materials”, says Stout, “really resonates with the way in which we are all trying to make sense of a world rapidly changing around us.”

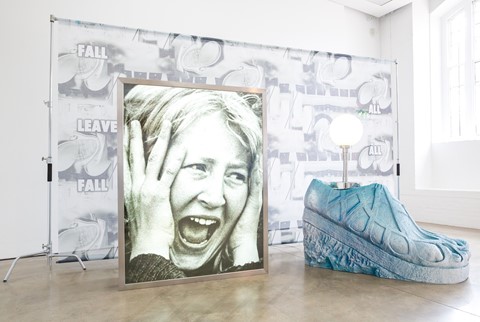

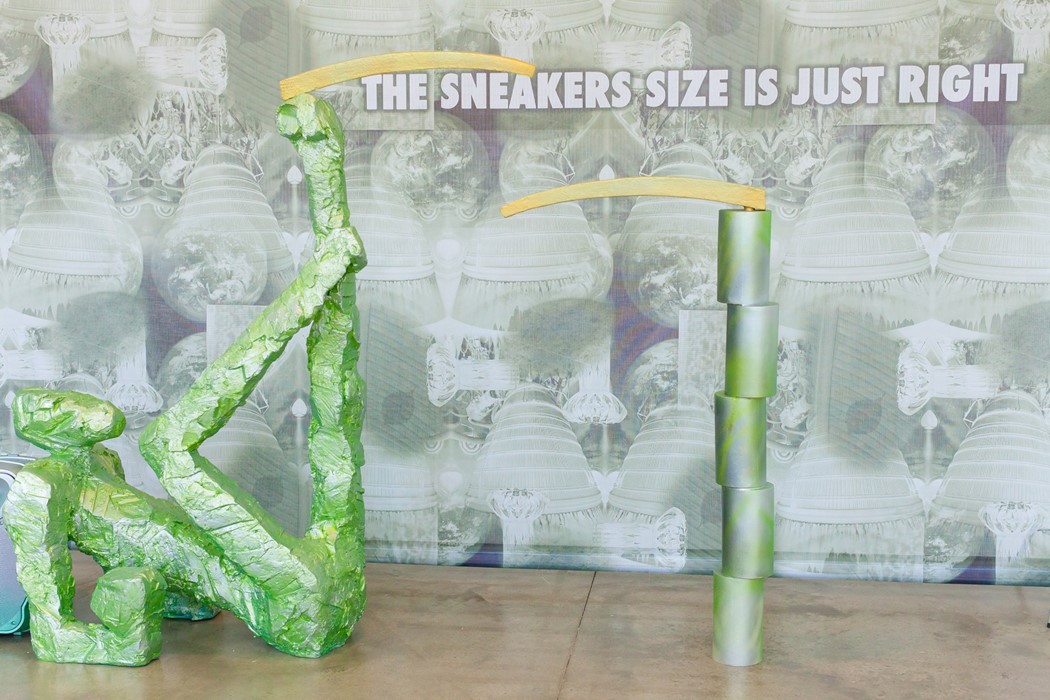

What? Walking through Flattened Metal is like navigating an unknown sci-fi territory that exists somewhere in between an archaeological excavation site and a kitsch video game. Neither description would offend Xiao, who draws as much on ancient relics for inspiration as she does on popular internet culture. The results? Installations that juxtapose objects from seemingly conflicting time periods and cultures – psychedelic, hyper-modern screen prints that serve to backdrop Baselitz-esque carvings (washed over with metallic green paint). “I like things that are bad taste because they can challenge something”, Xiao stated in a Rhizhome interview last year. That “something” is often the “flattened” way in which we view the world through a screen, or window, onto an equally collapsed digital environment wherein Mariah Carey can coexist with Pre-Columbian artefacts.

On the one hand for Xiao, this coexistence – or synchronic anachronism – means there is “no hierarchy” in the contemporary visual world. Kim Kardashian and the Mona Lisa have equal celebrity, especially when they appear in the same tweeted selfie. On the other hand, in some kind of Derridean sense, it means there is no definitive meaning – or discernible “origin” – to anything, which would make sense for an artist who eschews cultural pigeonholing. Playing on this network of ideas, Xiao’s three-channel video work Action (2014) presents us with a neat succession of “random” images, sounds and text mined from Google and YouTube, resisting any unifying explanation. “I want (the viewer) to feel like a detective”, Xiao said in a recent interview published in the Financial Times, which wouldn’t be a problem for anyone willing to untangle her stack of clues.

Why? Clearly, there’s a humorous tone suffusing Xiao’s cryptic work. Sculptures like Slight Dizzy and Rolling Beating (both 2014) – topping knobbly characters with an oversized umbrella and a straw hat – nod more to artists like Russell Maurice and Lucas Dillon, inspired by old-school cartoons, than they do to the “post-internet” category to which her work is often consigned. But, then again, you could make innumerable comparisons with Xiao’s corpus, and they may all be right. After all, there is no singular origin or meaning to her work. As Stout suggests, Xiao’s amalgamation of archaic and new sources implies that for her, “we don’t always understand what they are, or what their purpose is, so we can only react to them emotionally”. Indeed, her exhibit seems to say that in our time-warped world of information overload, perhaps the only thing we can rely on is our instincts.

Guan Xiao is on show at the ICA in association with the K11 Art Foundation until June 19, 2016.