The sprawling archive of Polaroid snaps behind the photographer's vivid, cinematic photographs is the subject of a fascinating new exhibition

British photographer Miles Aldridge has long been renowned for his uncanny ability to bridge the gap between fashion and fine art photography. His cinematic work for publications such as Vogue Italia – a collaboration that has been running for 20 years – was the subject of a major retrospective at Somerset House in 2013, and a selection of his prints are displayed in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria & Albert Museum

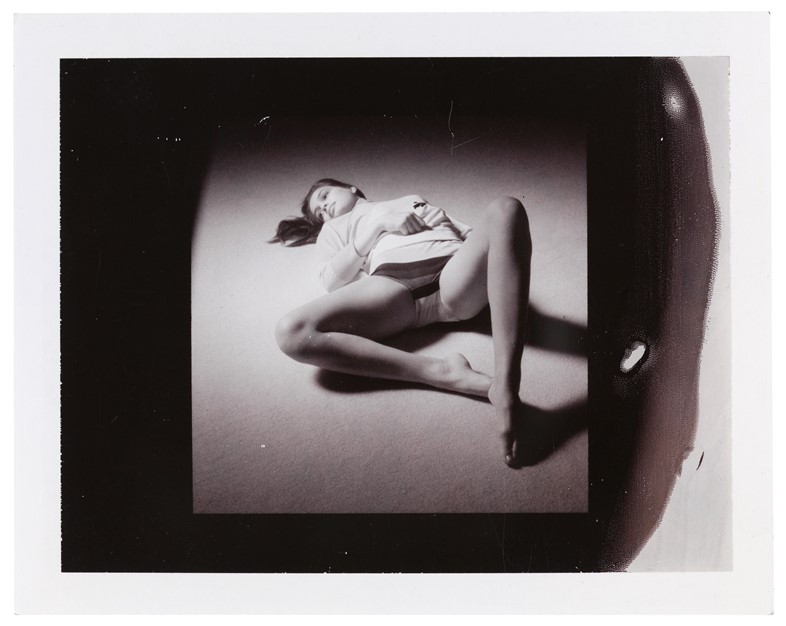

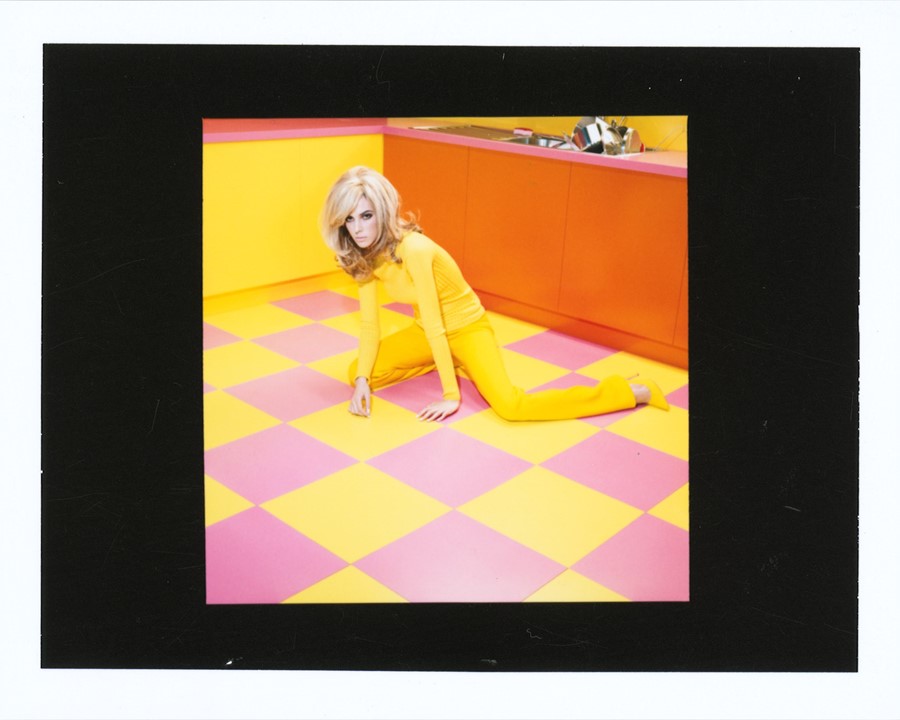

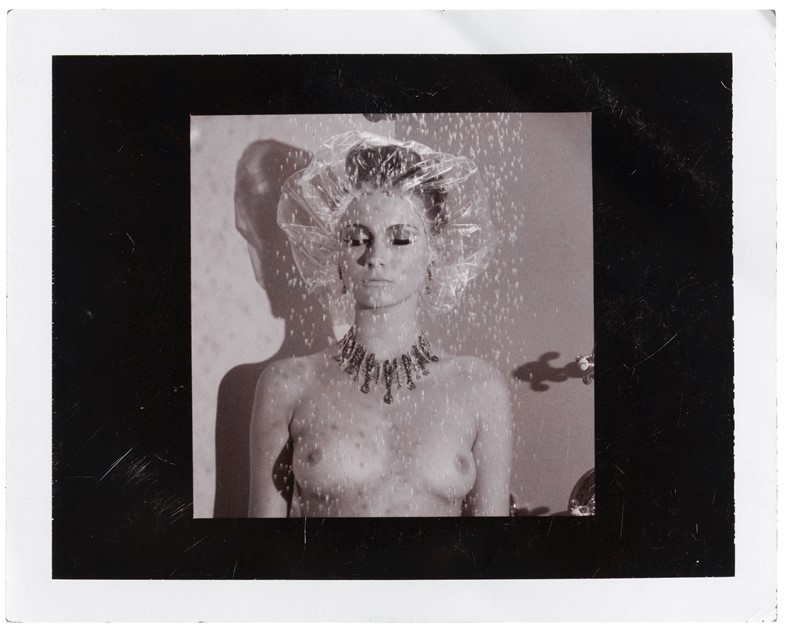

Aldridge’s depictions of women – housewives, mothers, pin-ups – in florid colours, their vacant gazes fixed away from the lens, turn the viewer into a voyeur. On the eve of a new exhibition of his Polaroid photographs, entitled Please Return Polaroid, and the publication of an accompanying book with the same title, he talks film verses digital, family values and eternal influences.

On his first camera…

“My father (the renowned illustrator and graphic designer Alan Aldridge) gave me his Nikon F in the 1970s when I was ten years old and I still have it. I remember we were on holiday in Norfolk at the time, it was one of those long days during the summer and he was trying to get rid of me because I was under his feet and he was on deadline for a job – he gave me the camera so I could entertain myself. My father originally bought the camera to photograph the Beatles with when he was working as the art director for Penguin Books, so it has a great provenance. He taught me to focus the lens on a person’s eyelashes when you take a picture of them, which I continue to do to this day.”

On keeping it in the family...

“As a child I’d sit on my father’s lap and draw with him all the time, inhaling his cigar smoke as he created these psychedelic pictures. When I was 14 I went to a photography course in the evenings and took photos of my 11-year-old sister Saffron. She started modelling from a young age. It was very inspiring to have a sister who wanted to be a guinea pig with photography, and a father who was endlessly drawing for a living; I thought that was the dream – to be able to support yourself through drawing.”

On the importance of Polaroid…

“I only shoot on film so Polaroids give me an idea of what the result will be. It’s never the same as the image I capture on film, only an approximation – the Polaroid is always less sharp, less colourful, but it’s the best way to ensure the light, colour and pose are how I want them to be. This was the way photographers worked when I started my career as a photographer in 1995 – pre digital cameras – and I stuck with it. Now I have an archive of two decades’ worth of Polaroids.”

On staying faithful to film…

“I’m a fashion photographer, so my job predominantly consists of taking pictures for magazines, but in 2005 I started exhibiting these images – particularly my work for Vogue Italia – and found that they could be enlarged more effectively if they were shot on a film rather than digital camera. Also, what I love about working in film is that you don’t have the security of digital, which forces you to focus your eye and mind, and push yourself because you have to shoot relentlessly in order to get the result that you want. The models in my pictures have to re-enact poses and actions again and again; emptying them of any emotion and expression so that they have the intensity of a Renaissance painting. They look as though they have been trapped in that role of the broken housewife.”

On his greatest influences…

“Alfred Hitchcock’s ability to make ordinary things seem very strange and sinister – a bedside table, hairbrush or bunch of flowers – has been a key influence. Whether it’s making beautiful things look ugly, or very normal things look strange, my aim is to create photographs that stop the viewer from turning the page of the magazine at a time when images are so casually thrown away.”

On women…

“Heroines are a more interesting subject to me than heroes. Many of the people who have influenced me – not only Hitchcock but Goddard and Fellini also – celebrated women rather than men. In art you are always trying to tell your story, and my story seems to be about these rather fragile, broken women.”