A new London exhibition highlights how the esteemed British artist inverted the female gaze before it was known to exist

Who? The first woman to be elected a Royal Academician since the founding members in 1768; first female artist to be named a Dame of the British Empire; president of the society of women painters; artist and social explorer Dame Laura Knight had a string of achievements to her name, but neither her entry into her life – a working class family in England – nor the late 19th and early 20th-century era in which she was working could have anticipated any one of them. Knight was born into a family of five children, so when her mother was widowed at an early age, the primary care of her younger siblings fell almost entirely onto the eldest child's shoulders. She succeeded in seeing them fed, watered and educated, as she would continue to later in her life, by sheer grit and determination – before spending a short time in French schools and taking herself off to an English art school.

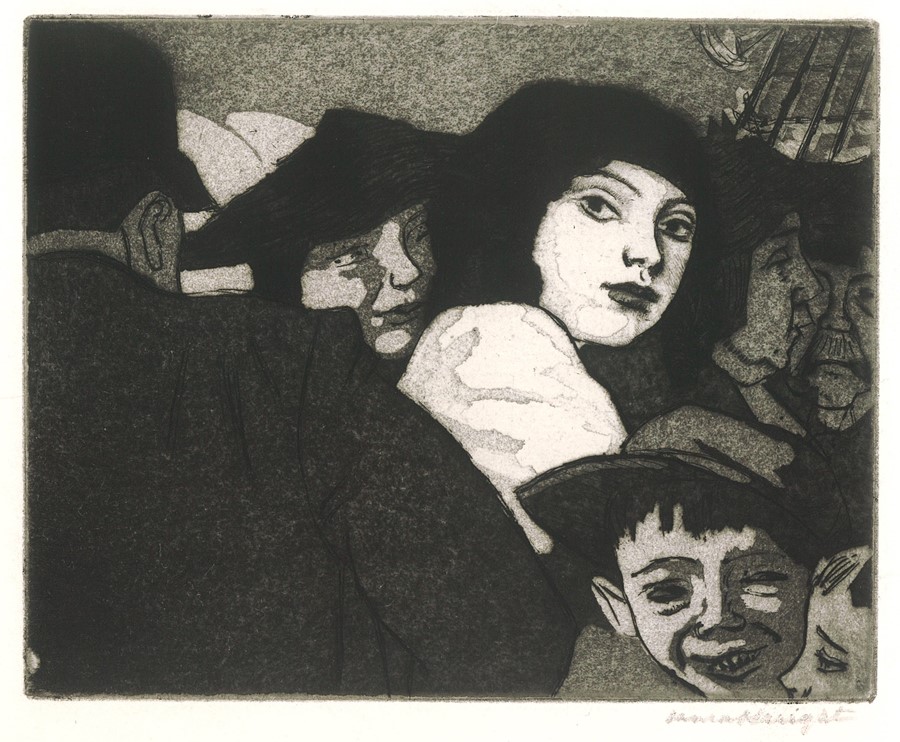

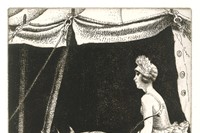

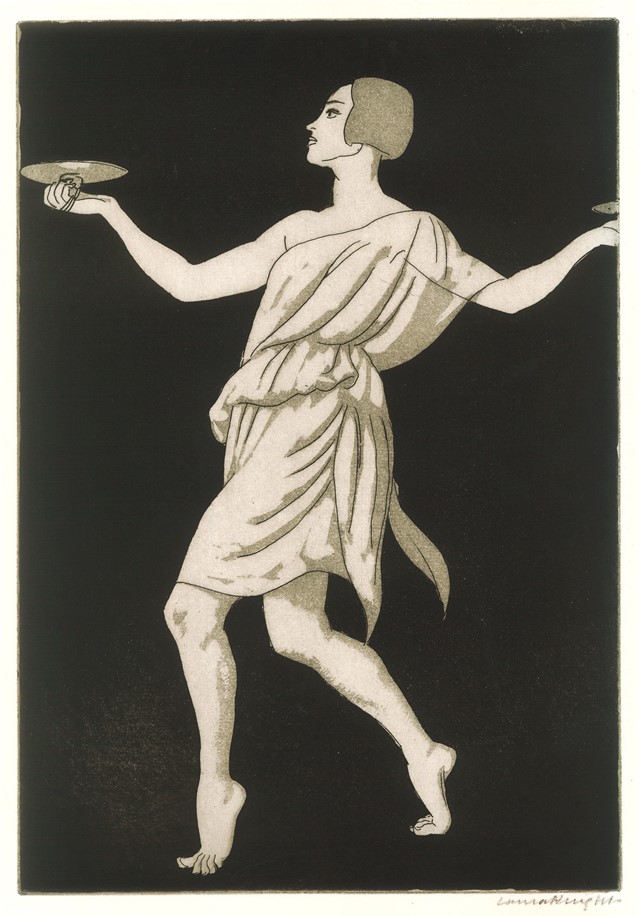

From war art to social documentary, Knight's tenacity and dedication to her subjects led her to explore unexpected corners of society. Not only did she carve a career for herself at a historical moment when it was near impossible for women to do so, but she was resolute in her determination to chronicle those members of society who were usually kept far from the art world's introspective limelight. "Her work is incredibly inventive," explains Robert Upstone, Director of British Art at the Fine Art Society in London, who has curated a small but insightful exhibition of Knight's etchings and aquatints for the Society this spring. "She locates herself within the 1920s and 30s, and within quite bohemian sections of society – whether that is the circus, with the gypsies, or the ballet. And she doesn't just go and sit with them for five minutes. She actually travels round with them; she makes appointments with the gypsies to meet them at Epsom, and things like that." At a time when social conventions were rigorously enforced, Knight continually immersed herself in social groups whose values and perspectives were very different to those of the world – and that focus drew attention from the critics, Upstone continues. "They were saying, why is she painting these people? It came back to the perennial question of sort of 'what is art?'"

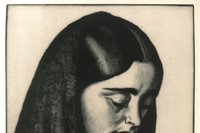

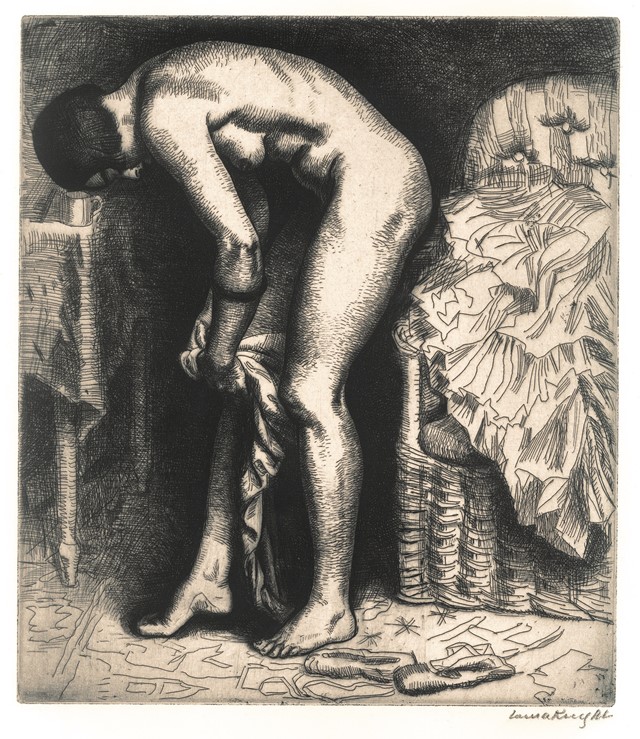

What? Knight's female gaze and tangible empathy for her subjects gives her work an unmistakably modern edge, even now – particularly in her Dégas-like depiction of the female form, which was groundbreaking to her early 20th-century viewer. In 1913, her revolutionary work Self Portrait with Nude, in which she depicted herself, unconventionally, in her workwear, painting a nude model – a piece which caused uproar in the press both because of her professional attire, and because female art students of the era were not permitted to draw from life. Her approach towards female subjects was at once intimate and empathetic – partly, Upstone notes, because she spent so long with them before drawing them. "These are not necessarily professional models, they are people that she knows and that she encounters in the changing rooms of the ballet, or of the theatre – people she relates to. That is a world away from being in a life drawing room in an art school and painting a model who you have no connection with and maybe you don't have that sense of identification with."

In her work, Knight was a dedicated multi-disciplinarian, mastering media from oils and watercolours to etching, engraving and drypoint over the course of her career, occasionally out of necessity as much as desire. "She didn't start etching until she broke her arm, as she couldn't paint," Upstone explains. "She is a very tough character, you know – she could either sit back and not do anything for three months, or she could think ok, what can I do and how can I do it? But she comes up with a very stylish, highly individual approach to using etching techniques that, again, marks her work out as unlike anybody else’s at that time."

Why? Contextually groundbreaking, but aesthetically traditional, Knight walked the boundary dividing the old and new, utilising her charm to ensure that she received professional support as and when she needed it to sustain her critical success. This delicate balance lends her a very particular place in the modern movement, says Upstone. "Her work is quite interesting, because on one level it's highly inventive and breaking new ground, but it is also traditional… It is not abstract and it is not in any way modernist, it is modern with a small M. It is accessible to a mass audience, and I think that is part of her continued appeal."

Laura Knight: A Private Collection runs until May 26, 2016 at London's Fine Art Society.