A new London exhibition charts the brilliant career of the west coast-born artist whose work is infused with 1960s psychedelia

Who? Born in California in 1940, Mary Heilmann studied ceramics, literature, poetry and sculpture in San Francisco, Santa Barbara, and Berkeley, before moving to New York in 1968. While in New York, she took up painting, experimenting with bright colours, drips and unorthodox geometries – a move which was particularly radical due to the fact the medium had been declared ‘dead’ and the majority of her artistic contemporaries were performance artists or sculptors. Nonetheless, she began exhibiting at Holly Solomon Gallery in the mid-1970s and then showed regularly at Pat Hearn Gallery in the 1980s and 1990s – Hearn and Solomon both being female art dealers whose navigation of the cut-throat New York gallery climate has been legendary.

A retrospective of Heilmann’s work entitled Looking at Pictures opens today at The Whitechapel Gallery. It seeks to consider the autobiographical themes that recur throughout her oeuvre – listed by the exhibition's curator Lydia Yee as "memory and biography, pictorial space, and the influence of popular culture," alongside more formal approaches to artistic style and practice. “Every piece of abstract art that I make has a backstory,” Heilmann has said. Each work is imbued with personal recollections or cultural references: the surreal beach life of the west coast, counter-culture, dreams and invented stories, and friendships with New York artists, poets and musicians all form the bedrock of Heilmann’s eclectic creative output.

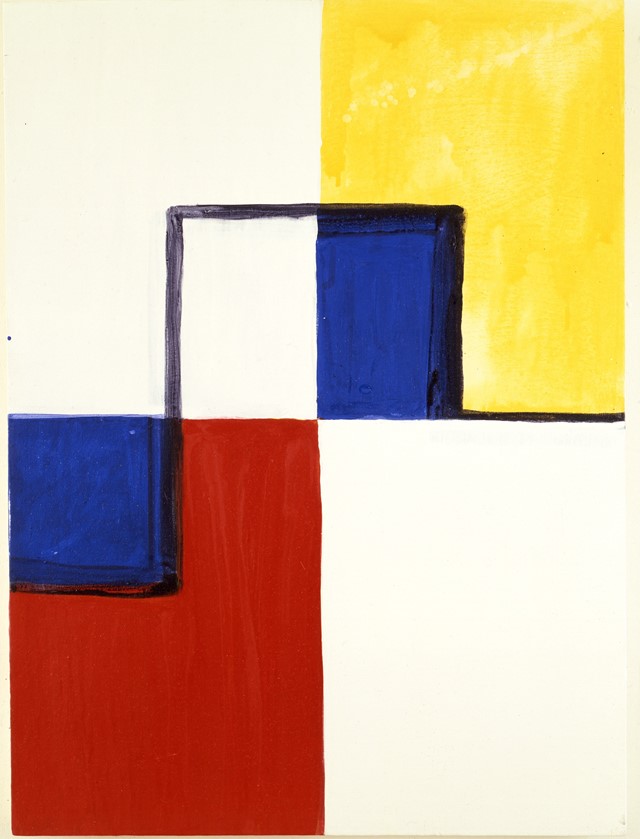

What? Heilmann’s early paintings and ceramics open the show. The First Vent (1972) was one of her first geometric works, inspired by the history of abstraction; it takes the shape of an awry grid. “The First Vent took Heilmann in two directions," Yee writes. "On the one hand, towards geometric abstraction as represented by grids and squares, and on the other to works that make reference to things in the world, particularly from the interior environment.” In order to make a similar tactile grid in Little 9 x 9 (1973), Heilmann manipulated and scraped the red paint with her hands, revealing the dark background underneath and creating a more textured surface. Incidentally, she was teaching art to children at the time, and cites finger painting with them as one of her inspirations for this work. The physical nature of working surfaces in ceramics translates into Heilmann’s choice of acrylic paint, able to be manipulated quickly while it dries.

The choice of colours often relates back to ceramic glazes, as in Ming (1986), which is influenced by blue-and-white porcelain of the Chinese dynasty, while the edges of all her canvases are painted – the picture is not intended to be a two-dimensional plane, but rather an object that extends into three-dimensional space. The influence of modern masters such as Mondrian and Matisse can be identified in Heilmann's paintings from the 1980s, with two aptly titled Little Mondrian (1985) and Matisse (1989). “Patterns recall patterns,” art historian Briony Fer suggests in her catalogue essay. “It is more like paintings can remember other paintings, just as a line in a song can carry in it the recollection of another version of itself.”

Upstairs, the exhibition continues with Heilmann’s digital slide projection, Her Life (2006), which juxtaposes images of her artwork with 35mm photographs she has taken over the years; “they are snapshots of things that I have experienced, but not family photos.” 13 minutes-long, and set to an eclectic mix of songs from Brian Eno, Jane Siberry and South Asian dance music, the slide show makes the relationship between Heilmann’s paintings and her own biography more explicit, imbuing them with personal significance. In the paintings, which date from the late 1970s to the present, biography is also granted a central role. Abstract in form, but imbued with emotional subject matter, they commemorate key moments in Heilmann’s life: subjects such as close friendships, places she has lived, worked or visited, or a rich appreciation for popular culture all explored.

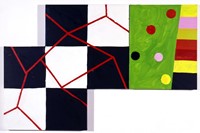

In her more recent works, Heilmann has been inspired by the landscapes of the American west coast, diffusing them with hallucinatory or psychedelic patterns. Waves, highways and ocean vistas are all depicted in relationship to the human body – the images are made so the viewer feels that they are physically in the water or on the road. No Passing (2011) and Maricopa Highway (2014) evoke road trips, road movies and video games through an evocative geometry, while Crashing Wave (2011) uses a rich interplay of green and blue paint to depict the surf along the ocean’s coastline.

Why? The exhibition spans Heilmann’s prolific five-decade career, from early geometric paintings made in the 1970s, to more recent off-kilter canvases in neon or clashing colours. Alongside painting, a selection of ceramics, and works on paper are on show, allowing further access into her eye-popping and playful approach to art and abstraction, and the watercolour studies have never been exhibited in public before. Twelve candy-coloured wooden chairs, Sunny Chairs for Whitechapel (2016), are also on display alongside the paintings. Heilmann, who regularly builds her own furniture, has installed these chairs as an invitation for viewers to sit and discuss her work communally. The chairs become part of the composition and by extension people sitting in them do too.

Gaining major recognition in the 1990s, Heilmann has exhibited widely in Europe and the United States, however this exhibition is the first major UK survey of her work in 16 years. The director of the gallery, Iwona Blazwick, has written that Heilmann’s work finds “an appropriate platform at the Whitechapel Gallery – her exhibition follows on from a century-long trajectory of abstract painting… Hers is a practice that connects with these figures yet offers a vision that looks forward, at once commemorative and experimental, tentative and protean.”

Mary Heilmann: Looking at Pictures runs until August 21, 2016 at the Whitechapel Gallery, London.