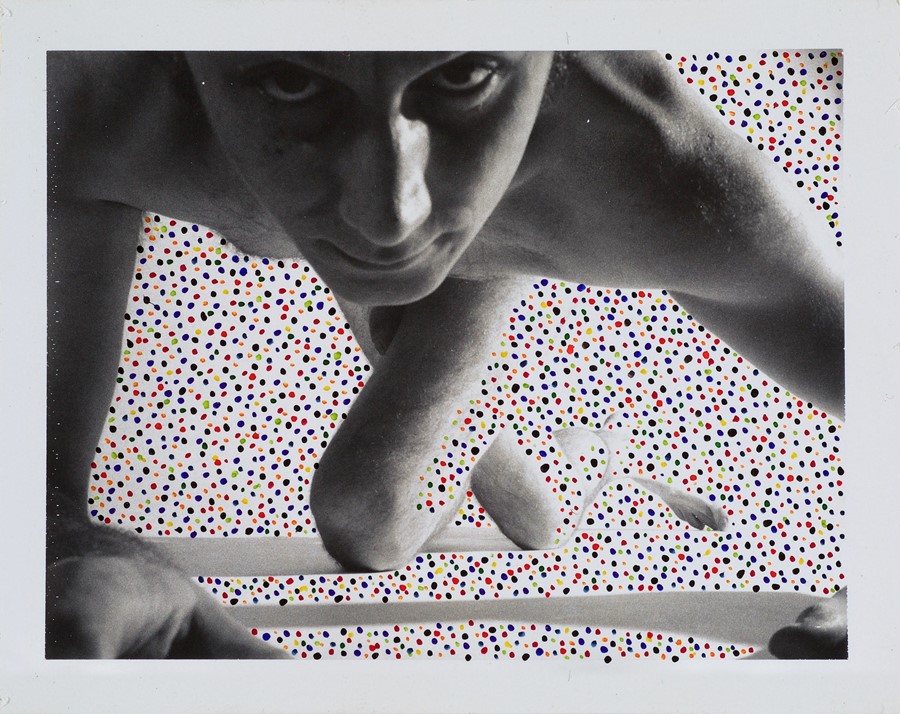

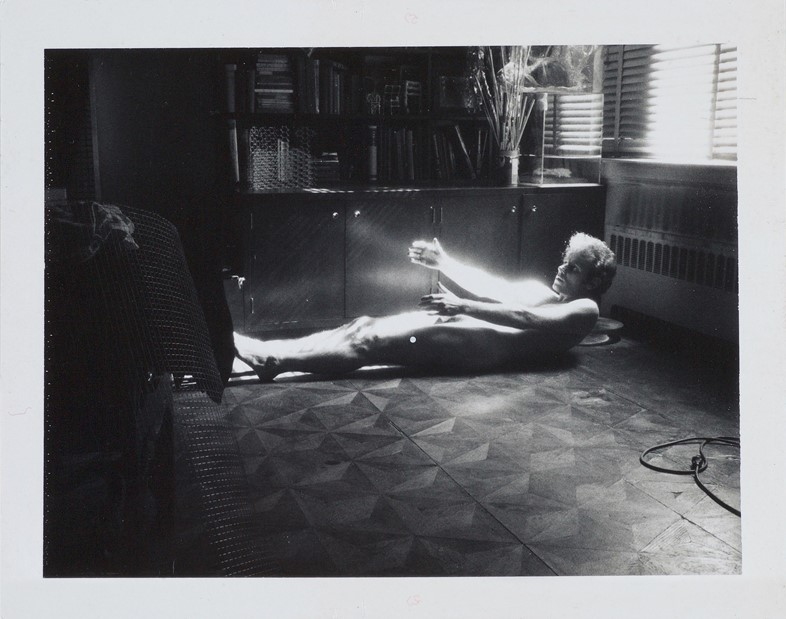

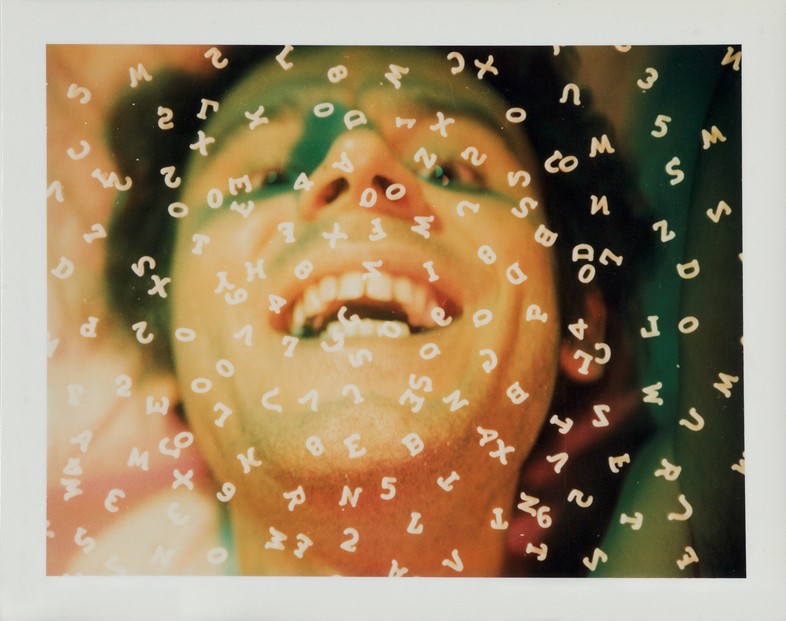

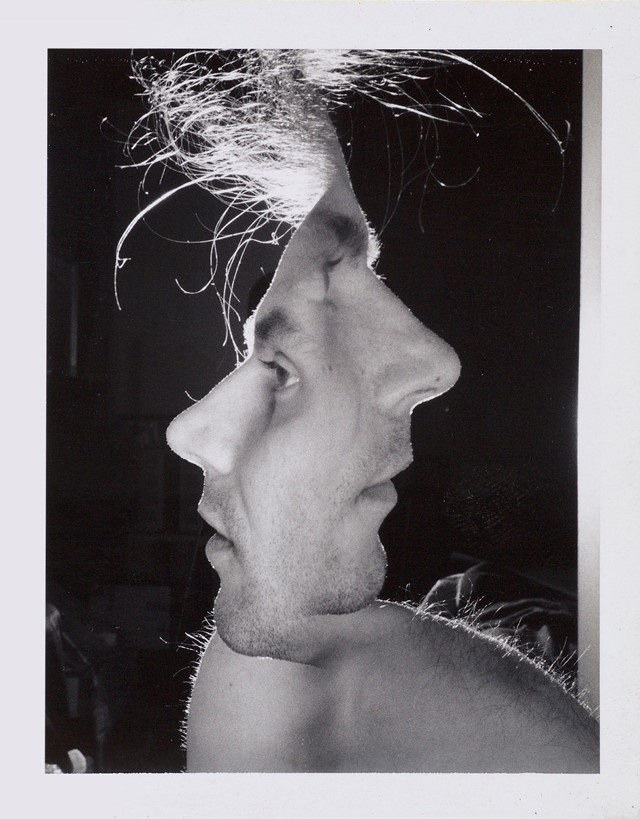

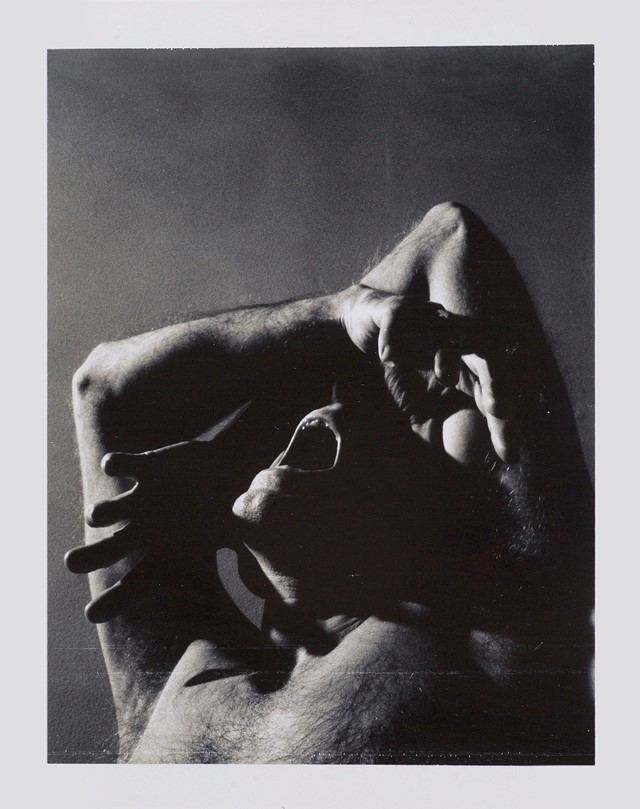

47 years after they first shocked the art world, Lucas Samaras' AutoPolaroids are going on display in a new exhibition, and they're as pioneering and as playful as ever

"What’s the name of that gallery in London, in the park, it starts with an 'S'?" It’s late afternoon and, by way of a long-distance phonecall, I’m engaging in what might be a general knowledge quiz with Lucas Samaras, the 80-year-old, New York-based artist who first scandalised the art industry some 50 years ago with a series of manipulated, nude self-portraits taken with a Polaroid camera. The gallery he’s thinking of, as it turns out, is the Serpentine. "I had a show there in 1986," he continues, "but I don't think I got a single notice from any of the London papers."

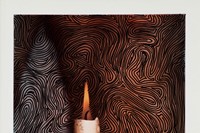

This, he explains, wasn’t unusual. His AutoPolaroids, a series he worked on from the late 1960s onwards, present an unflinching study of identity – the human body, nude, playful, distorted, the photographs often decorated with paint, or with the film’s own wet dyes – and radical as this was, they were regularly spurned by the then tightly laced art industry. He found approval in other sources, however. “The director who held the exhibition told me that one day – what's his name, the most famous painter in England? The screaming heads?” We go backwards and forward again for a moment before we come to Francis Bacon. “Bacon! There we go! He came to see the show with his boyfriend at the time, and afterwards he said something very strange – it sounds like self publicity for me, but I loved it so much that I couldn't forget about it – he said, ‘well, we don't have to think about Hockney anymore!’ I was thrilled. That was just as good as having ten reviews in London."

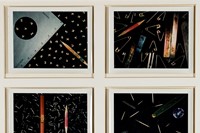

The comparison isn’t so outlandish. Samaras, like Hockney, has worked prolifically since enrolling at Rutgers University in the mid-1950s, dabbling in painting, drawing, performance and sculpture over the course of his long career. He collaborated closely with Allan Kaprow, pioneering some of the very first ‘happenings’ to take place, and playing an instrumental role in the Fluxus movement. He was part of the university’s famous ‘New Jersey School’ alongside Roy Lichtenstein, George Brecht and Robert Whitman, and posed for George Segal’s plaster sculptures. He’s even reported to have played in a fledgling rock band alongside Andy Warhol, Claes and Patti Oldenburg, Jasper Johns, La Monte Young and Walter De Maria. He has held hundreds of exhibitions, is included in the MoMA’s permanent collection, and has been featured in countless art publications. And yet, he has yet to truly achieve great acclaim.

When it comes to his photography, Samaras is under no illusions as to why. “That was a period when nudity wasn’t allowed, you know. It was like, what the hell are you doing?” And yet, he had been working with the nude figure in his painting for many years before turning to the camera. “When I was painting in the late 1950s in my apartment, I would draw myself, nude. In the bottom of my mind I thought I would like to have my whole body photographed, but I had no information, no knowledge on how to go about it. I never took a class in photography. In high school I did buy a Voigtländer, a small little fifteen-dollar thing, but the pictures it took were just horrible.”

In the mid-1960s Samaras began working in collaboration with other photographers, but found the process to be too restrictive. “It wasn’t modesty. It was just I wanted to have more freedom.” He found this in a Polaroid camera, which he started using in 1969. “I loved Polaroids because with just a click, you got some nice blacks, some nice whites, the in-betweens. I just went to town. All of a sudden you do something – either you know what you’re gonna do, or you just did it – and you go, ‘wow’. It’s like fate has given you something to work with.”

The images made as a result of this experimental period are now the subject of a new exhibition at New York’s Craig F. Starr Gallery. Here Samaras shares his wisdom on nostalgia, conforming to societal pressures, making friends with artists, and why he’s absolutely not a narcissist, no matter how many times he's been labelled as one.

On how he got his big break…

“I had already spent maybe ten years making art in New York, but when I took these pictures, people were kind of shocked. Embarrassed is more like it. Here and there I would find somebody who would not be embarrassed, so, they made me think ‘gee, maybe I'm doing the right thing?’

At that time I knew a couple who ran Art in America. She was the editor. They had bought some of my work over the years, and they had invited me to dinner one evening, so I thought I’d take one of the photo albums I had. I took it there, and opened it, and on the first page, she said ‘my God, I’m gonna publish this!’ Anyway, she was thrilled about it, which shocked me no end, but you don't know how good it is to get like 20 rejections, and then one positive thing. She published them in a very short time. It began in late 1969, and by '70 it was published. It was 16 pages! I mean, that's like an angel giving you a gift.”

On working across different media…

“I have no favourite. For me, making art is like having a partner, a living partner. In a sense I'm probing myself, I’m saying, ‘OK, what else is in your mind? You've gone to museums, you've seen shows – how the hell do you push your mind to do something that interests you, but is different from what you did before?’ And then I would focus everything on that new thing, whether it's drawings, or something with fabric, or whatever. It's a need to open up a new part of my brain.

Usually, somebody makes a mark, and then he or she sells the mark, and says ‘OK, I'm gonna do a couple more, two or three, four, five...’ and you have a lot of marks, you know? And then you die, and they say ‘what the hell is it?’ What the hell did you do, what did you discover? Well, at a certain point, that's what I'm saying to myself: ‘enough already, what else is there?’ There has to be more than just one thing, because the brain's too complex not to have other stuff in there. And then I feel so possessive of the next thing that I can't just flick through it, I have to exhaust it in some way.”

On the difference between narcissism and a careful examination of onesself…

“It’s part of the culture, you know; everyone uses the word narcissism and they’ve been using it for years. The narcissistic myth is one thing, but how adults do things that are believed to be narcissistic is something else. For me, most of the time I never liked the pictures – I just didn’t like the way I looked. You need a picture or a mirror to see how you look, and I just didn’t like the damn face. But a strange thing happens over a period of ten, or 20, or 30 years, where if you look back you say ‘boy, there’s a period of five years where I look stupid, then there’s another period of ‘ooh, not bad,’ then another period of looking stupid again.

I never thought I was being narcissistic, I was being somebody who wanted to do something. For a while I did nude pictures of other people, but then I felt more embarrassed painting pictures of them nude, than of painting myself nude. Your interpretation of yourself or of what you’re doing is a little different to society’s version, for the same reason that if you do something that society says ‘ooh, that’s taboo!’ you say, ‘oh screw you, that’s not taboo’.

Some people are born into society, they’re dripping with society. If their technique is good enough they can pass by, they don’t have to be shocking. They just can be beautiful.”

On shaking off society’s pressures to conform…

“It has to do with exchanging all the stuff that was put on me by the culture, by parents, by relatives. There are all kinds of restrictions – ‘don’t do this, don’t do that,’ ‘eat this, don’t eat that.’ And it depends at what point you decide, ‘OK, enough already, I’m gonna do what I want. Relatives might be shocked, but it’s not gonna hurt anybody.”

On befriending artists, and the competition that follows…

“Concerning artist friends, usually, the friendship part lasts only a year or two. Then jealousy comes around, and then you really can't stand the people that you thought were friendly. There's a confusion as to whether somebody's getting what they deserve, or what they struggled to get themselves regardless of whether they were good or not. The first couple of years when an artist gets attention, that's when he or she gets crazy. They're just out of their depth, out of their mind. It takes years for them to settle down. It's a fluctuating thing, how you see people that you've known.”

On nostalgia…

“People of a certain age say, ‘oh my best time was in the 1970s, or the 60s, or the 90s’. I think, for me, all of them were best times. But there's also a sweetness about your past – the older you get, the more you say ‘wow, I was alive then!’ And then a funny thing happens – when you dream about them, often you dream about when they were young, when they looked good. When they had the right weight, the right face. I'm talking about just the way they looked, forget about whether they were cruel, or generous or whatever. Just that. The physical presence, in a dream, that kind of fascinates me. I'm glad that I see them in a positive time.”

On advice to young artists trying to make it in the industry today…

“Oh, I wouldn't touch what's happening today. In my time there were ten, 20, 100 artists around. Now there are millions. How could I say anything about the millions?”

Lucas Samaras: AutoPolaroids, 1969-71 runs until August 12, 2016 at Craig F. Starr Gallery, New York.