From vivid and voluptuous Nanas to a sculpture park inspired by a deck of tarot cards, the French sculptor's glittering legacy lives on in a new London exhibition

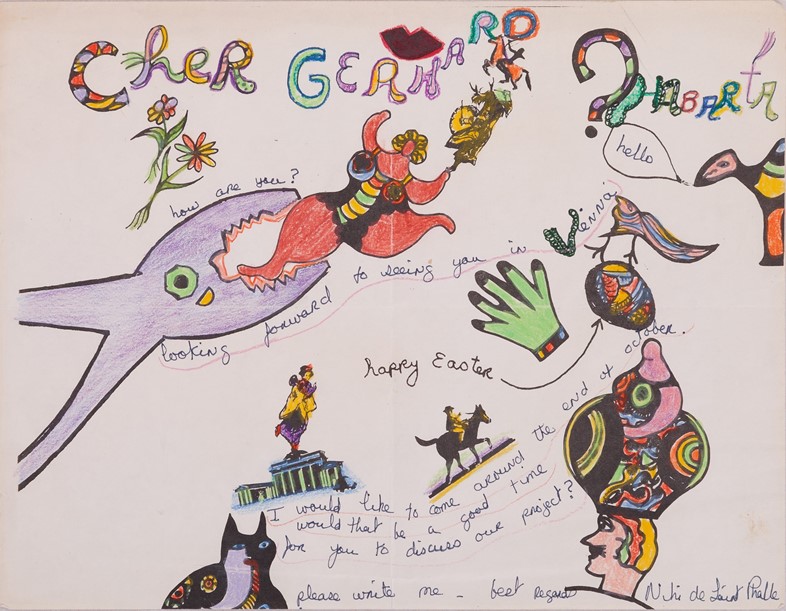

Who? As a young girl in the 1930s who had recently moved with her family from France to the US, Niki de Saint Phalle was expelled from a prestigious boarding school in New York City for meticulously painting fig leaves red on the school’s statuary – a cardinal sin, as far as the governing body was concerned. Little did they know, the sense of rebellion which drove the creative act, fuelled by a desire to beautify and add joyful colour to the world around her – was to become a recurring theme threading through Saint Phalle's personal life and artistic career.

Saint Phalle was an artist of many guises: rebellious and avant-garde on the one hand, but also a freewheeling bohemian and popular celebrity on the other. She was the art star on Andy Warhol’s arm, the feminist shooting canvases that exploded in paint like gushing wounds, the young and beautiful model, the campaigning activist, and the thoughtful grandmother building swirling playgrounds for younger generations out of shining tiles and bulbous concrete.

She learned to reject norms early on. At 18, Saint Phalle started modelling and married author Harry Mathews, moving to Cambridge, Massachusetts and giving birth to her first child in 1951. Frustrated by the stifling world of mid-century domesticity and traumatised by the effects of male domination – including being sexually abused by her father – Saint Phalle suffered a nervous breakdown in 1953. After a traumatic period of shock treatment, she turned to art as a form of therapy. It was through sculpture and painting that she taught herself to transform inner tumult into guiding totems of strength.

Moving to Majorca in the mid-1950s, Saint Phalle was taken by the shimmering universe of Gaudí and began similarly using sculpture to imagine new shapes the world could take. Her famed voluptuous, jazzy Nana sculptures from the 1960s, for example, celebrated the free and unrestrained female figure. They were glorious rejections of the serious pressures Saint Phalle felt to conform to beauty standards, and a way to imagine a world where these relentless standards didn’t reign.

Once she’d left her first husband in the mid-1960s, Saint Phalle then married fellow artist Jean Tinguely in the 70s, beginning what would become a fraught yet inspiring and collaborative relationship that saw the pair nicknamed the Bonnie and Clyde of the art-world. After a lifetime entrenched in Europe and its sensibility, Saint Phalle eventually moved to California in 1994, where she died in 2002 after spending the latter half of the 20th century working on public art projects, and donating her pieces to various museums across the globe.

What? Saint Phalle’s work has long been informed by sculpture – even her early works, bound to canvas, would use contorted chicken wire, papier mâché and found objects to explode from the surface. These pieces often depicted archetypal female figures, from looming brides covered in knotted lace to motherly earth goddesses with tangled manes.

Her first hit came about through her shooting paintings, for which Saint Phalle fixed bags filled with paint onto canvases with white plaster before aiming at them with a gun. There was something rebelliously incongruous about the image of Saint Phalle, dressed all in white with a beautifully made-up face and hair, firing at these dusty depictions of men in suits and baby dolls.

In 1966, Saint Phalle collaborated with Tinguely on a large-scale sculptural installation, a giant ‘she-cathedral’ called Hon-en-Katedrall for Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden. This rainbow-coloured reclining figure recalled the joyful, celebratory Nana sculptures that the artist is most often remembered for, but this Nana also had a door-sized opening between her legs for visitors to enter.

While these free-spirited Nanas are Saint Phalle’s hallmark, some works from the period took darker turns too – surreal films that eerily related to sinister memories and dwelled on nightmarish, intimate themes.

In 1979, Saint Phalle drew on the luscious worlds of Gaudí and other mosaicked public spaces, deciding to create her own sculpture park. Acquiring land in Tuscany, she set to work on her sparkling sculptures inspired by tarot cards, eventually forming a luminous, elusive space of shocking pink and looming, creamy ghosts. This immense project then informed a series of demented playgrounds designed by Saint Phalle in the latter half of the 20th century, deftly combining her free-wheeling imagination with environmentalist themes.

Her career ended much as it had begun, with illuminating yet rebellious energy that had Saint Phalle transforming environments around her into something spectacularly Other. What started as a flash of red on leaves as a child became flamboyant Nanas in Spanish gardens and city streets; Saint Phalle dressed the world in visions from the unconscious but also transformative glowing tiles, shimmering stones and speckles of rainbow paint.

Why? Je Suis Une Vache Suisse opens on June 17 at Omer Tiroche Contemporary Art Gallery in London, and it brings together previously unseen or relatively unknown work by Saint Phalle. It includes a menagerie of mythical animal sculptures and works on paper, all of which emphasise her enchanting and imaginative engagement with the natural world.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Je Suis Une Vache Suisse runs until September 10, 2016 at Omer Tiroche Contemporary Art Gallery in London.