A rare exhibition of the early 20th-century photographer's pioneering works places his surreal compositions and startling advances in colour back in the limelight

Who? American photographer Paul Outerbridge was one of colour photography's most innovative pioneers. Born in New York in 1896, Outerbridge demonstrated creative prowess from a young age, working as an illustrator and developing set and lighting designs for amateur theatre productions while still in his teens. By 1917 he had enlisted in the US Army, where he began experimenting with photography, and three years later he enrolled at Columbia University to study it formally. His aptitude for the medium was immediately apparent; within a year the young photographer was capturing images for such prestigious magazines as Vanity Fair and Vogue.

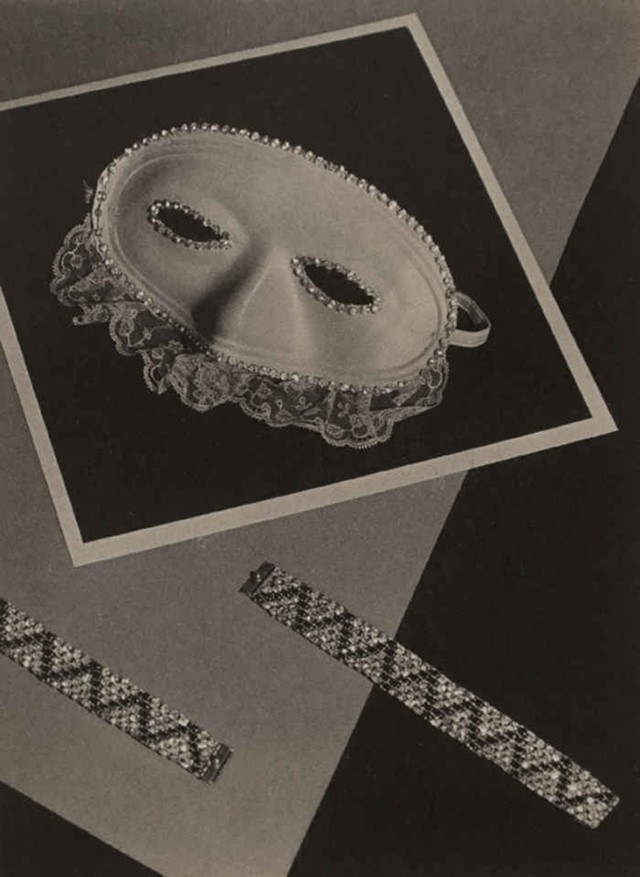

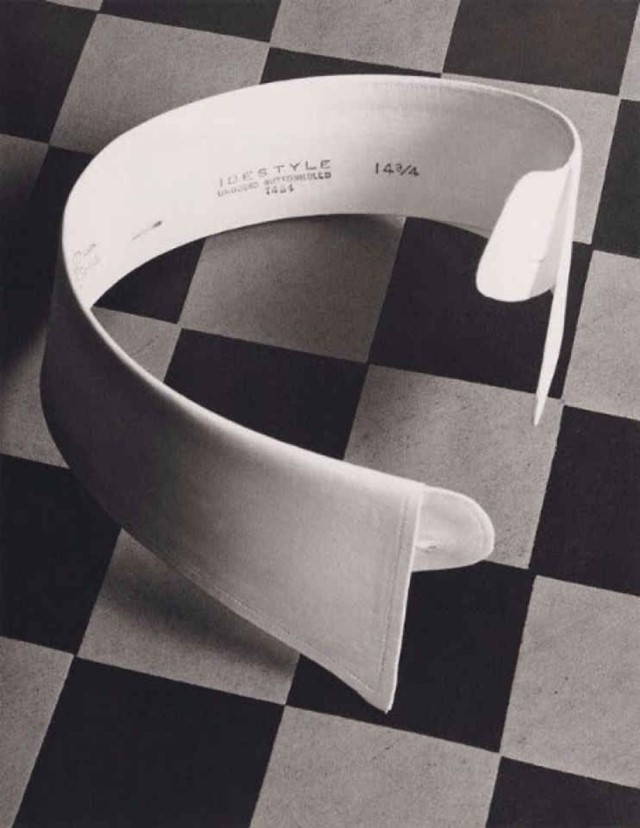

Outerbridge's early black and white shots were notable for their technical precision and original composition; he boasted a remarkable skill for arranging ordinary objects in an extraordinary manner with distinctly surrealist undertones, and was soon in high demand among advertisers and commercial clients. His resulting economic success was rare for such an experimental artist, and allowed Outerbridge an unusual freedom to work on his fine art photography alongside his commercial work, as well as facilitating a short but impactive sojourn in Paris.

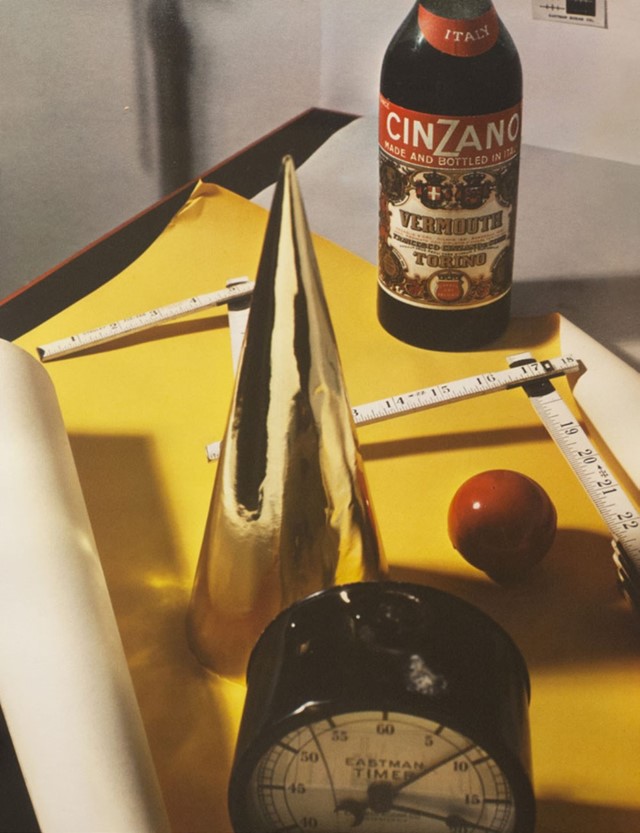

It was upon his return to New York from the French capital, in around 1930, that Outerbridge developed a burning desire to photograph in colour, and he quickly began a lengthy investigation into new processes to facilitate this. He spent several years in the mid-30s perfecting the three-colour carbon transfer printing process – a complex and expensive technique that produced vibrant colour prints from black and white negatives – and thereafter reinvented himself as one of the most expert and expressive colour photographers of his day.

What? What set Outerbridge apart was his unique ability to create semi-abstractions from commonplace objects – be it a Christmas tree bauble or a seemingly random collection of items, like the set square, gold paper hat, alarm clock and red ball that accompany the vermouth bottle in his famous 1937 advert for Cinzano – courtesy of his particular attention to pattern and lighting. He was a total perfectionist, sketching out each shot, complete with lighting specifications, on paper before painstakingly recreating it in his studio. Such immaculate pre-planning enabled Outerbridge to explore spatial relationships in a manner that drew comparisons to the work of the Modernist painters, while his merging of the high and low in terms of subject matter reflected the artistic zeitgeist of the age, from the work of the surrealists and cubists to that of Duchamp (who kept Outerbridge’s 1922 image, Ide Collar, pinned to his studio wall).

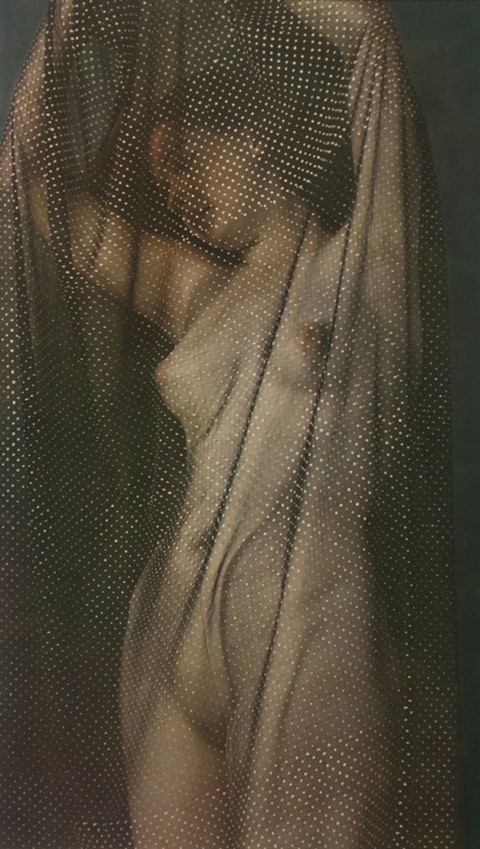

Outerbridge was particularly fascinated by the shapes and chiaroscuro created by the human figure, and some of his most interesting abstracted studies can be found in the many nude portraits he took (most of which were banned from being exhibited during his lifetime owing to the exacting poses of the models). "The advantages of photographing the nude are few," he once noted, "because nudes have very little, in fact practically no commercial value. The disadvantages are many because it is the most difficult thing to do from every point of view." But it is safe to say he mastered it: whether draped in a translucent black scarf punctuated with tiny white dots, or sprawled languorously across a red velvet sofa, the female figure has rarely looked so mysterious.

Why? Outerbridge’s colour prints are extremely rare, due to both to the laborious technical processes they required and the artist’s uncompromising standards. Thus, the new retrospective of his impressive oeuvre at New York's Bruce Silverstein Gallery, which brings together many of his finest colour works alongside a no-less-impressive array of black and white pieces, is completely unmissable.

Paul Outerbridge is at Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York until September 17, 2016.