A new exhibition at the Berlinische Galerie broaches unexplored territory to form a fresh and non-Eurocentric view of Dada

From its very inception in 1915, the Dada movement has always been heavily influenced by non-European cultures. It was founded in the Cabaret Voltaire, Hugo Ball’s infamous Zurich nightclub; an institution run by a group of anarchic artists and writers who met for soirées of radical music, spoken word and masked dance performances – rituals that reenacted African ceremonies – designed to push the limits of the performers and their audiences.

The First World War, too, had a powerful part to play in the expansion of Dada as an artistic movement: as fighting took hold of Europe, the experimental movement spread to Berlin and then to Paris, flourishing with the passionate anti-war sentiment which preceded it. Little by little, Dada became a reaction against the nationalist and colonialist mindset prevalent in European thinking at the time. As the war continued, the Dadaists' urge to get beyond Europe became manifold: their non-conformist and anti-traditionalist attitude pushed them to look to the art being created on other continents, searching there for new ideas, aesthetics and forms of artistic expression that would contribute to their mission.

This August, in celebration of the movement's centenary, a new exhibition at Germany's Berlinische Galerie presents Dada Africa: Dialogue With the Other – a groundbreaking investigation into the connections between Dada and non-European cultures that simultaneously re-examines the ascension of the movement from Zurich nightclub to contemporary art gallery from uncharted perspectives. The show comprises 120 works, rare archival material, and a collection of indigenous artifacts from which the European artists borrowed, originating not only from Africa but also from America, Asia and Oceania. It makes for a fascinating overview: a sketch for a costume by Sophie Taeuber-Arp is displayed alongside the Native American Hopi Katsina doll from 1900 that inspired it, while a Congolese nkisi n’kondi figure made of glass, textiles, metal and wood provides a revelatory new reading of Raoul Hausmann’s assemblage Mechanical Head (1920). Elsewhere, Marcel Janco reinterprets masks from the Ivory Coast and Cameroon.

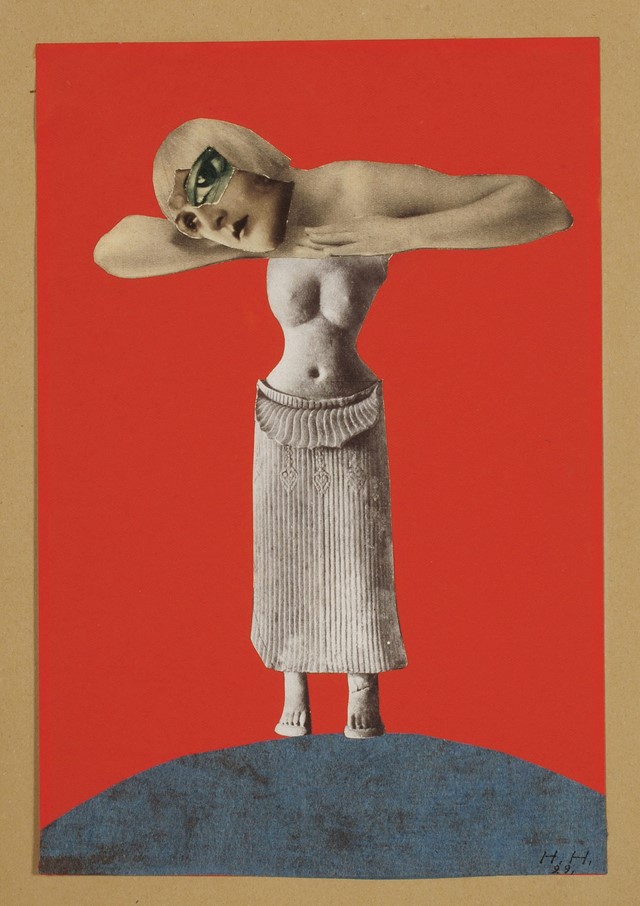

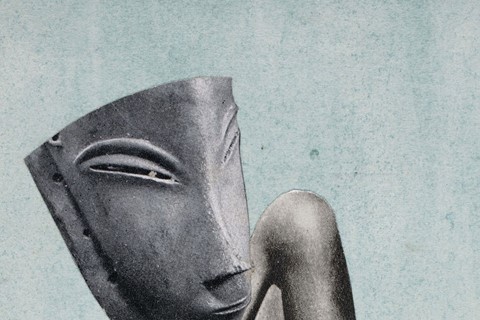

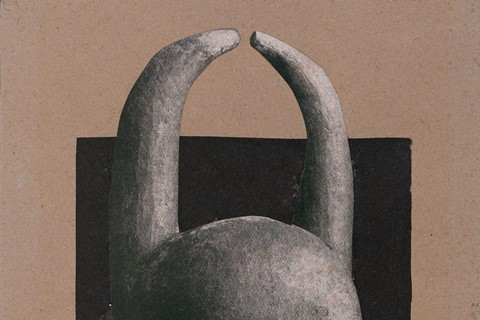

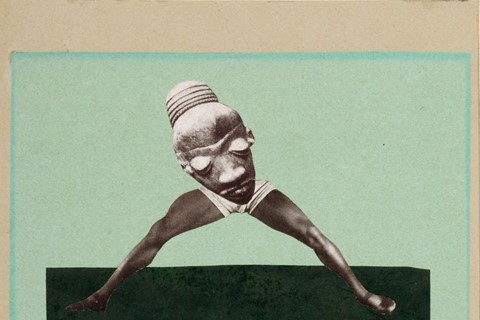

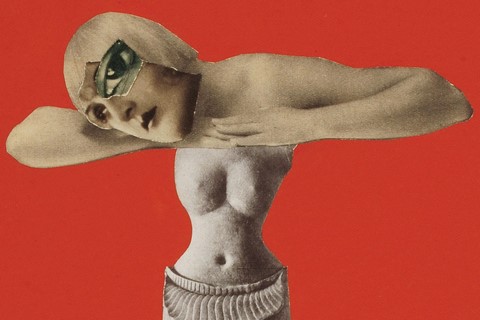

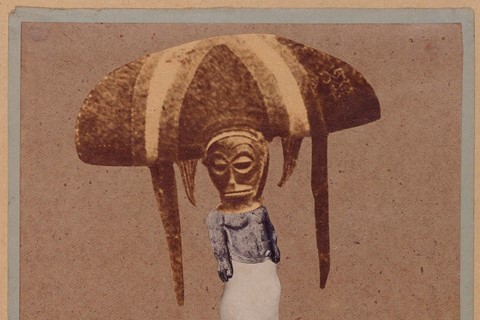

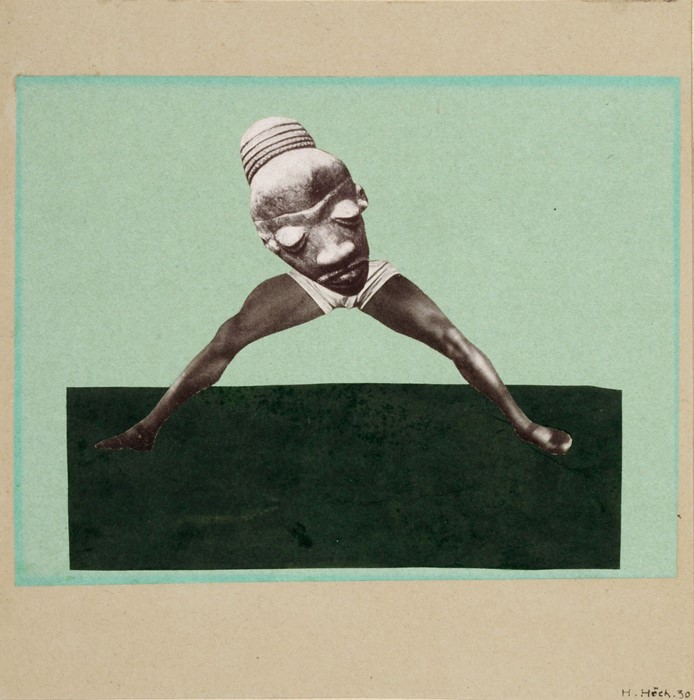

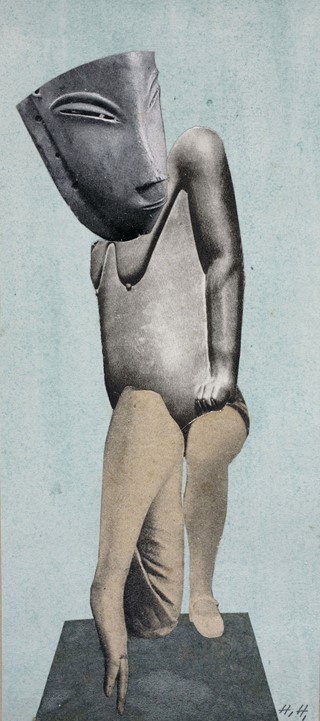

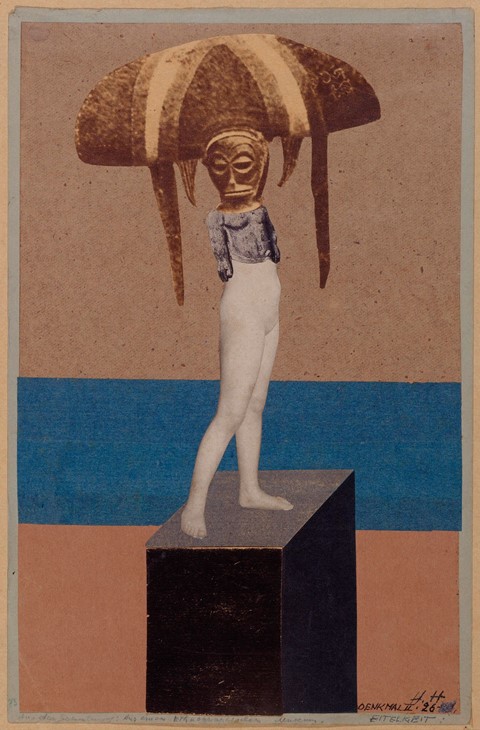

Perhaps most fascinating of all, however, is the series of photomontages by trailblazing artist Hannah Höch, from her series From an Ethnographic Museum (1930). One of her most searingly political and elegantly composed bodies of work, Höch’s cut-and-paste creations juxtapose European female figures and images of Africa with sculpted male bodies and emotive masks, torn from museum catalogues. One remarkable example brings together a 10th-century Khmer Empire sculpture of a female torso, with an exact replica that appears in one of her collages. Höch’s seamless merging of apparently opposed cultures – male and female, European and African, coloniser and colonised, documenter and documented, bourgeois modern and primordial tribal – made for a spiky statement against Nazi Germany and the ideals of western beauty, revealing the proximity of cultures and the farce of a cultural hierarchy.

The appropriation of non-western art created a nifty means of articulating Dada’s aesthetic and ideological revolution, but the act of borrowing from other cultures isn’t free from its own complicated political implications. The exhibition raises these questions about the exchange and use of cultures – what is lost and what is gained in the importing and exporting of art and objects – by illuminating the impact of non-western art on the movement. The curators have divided works into five key sections to survey the breadth of this influence, from the way objects and art were presented and performed, to their formal and aesthetic aspects. The exhibition is not only a statement about Dada’s evolution and legacy, but one that picks at the way cultural history has been constructed, and the importance of reassessing our relationship to it.

Dada Africa: Dialogue with the Other runs from August 5 until November 7, 2016, at Berlinische Galerie, Berlin.