Between 1983 and 1999 the visionary American filmmaker captured the face of every actor he encountered on his point-and-shoot camera, compiling an enthralling album of icons in the making

Who? American director Gus Van Sant is one of the most ambidextrous filmmakers in cinematic history; fearlessly independent and uncompromising in his vision, he can switch from creating deeply enigmatic movies with complex, fragmented narrative stuctures like Elephant or Paranoid Park to whipping up a no-less-captivating blockbuster biopic of Harvey Milk. Whatever he presents us with, viewers of Van Sant's work are plunged headfirst into his carefully constructed worlds, transported by his all-engulfing, frequently experimental cinematography and skill for drawing out exceptionally emotive performances from his actors (think: Good Will Hunting or My Own Private Idaho). He also has the remarkable ability to tap into the American zeitgeist, his films, whether from the early 80s or the current decade, always offering up some sort of conscious or subconscious reflection of the country's state.

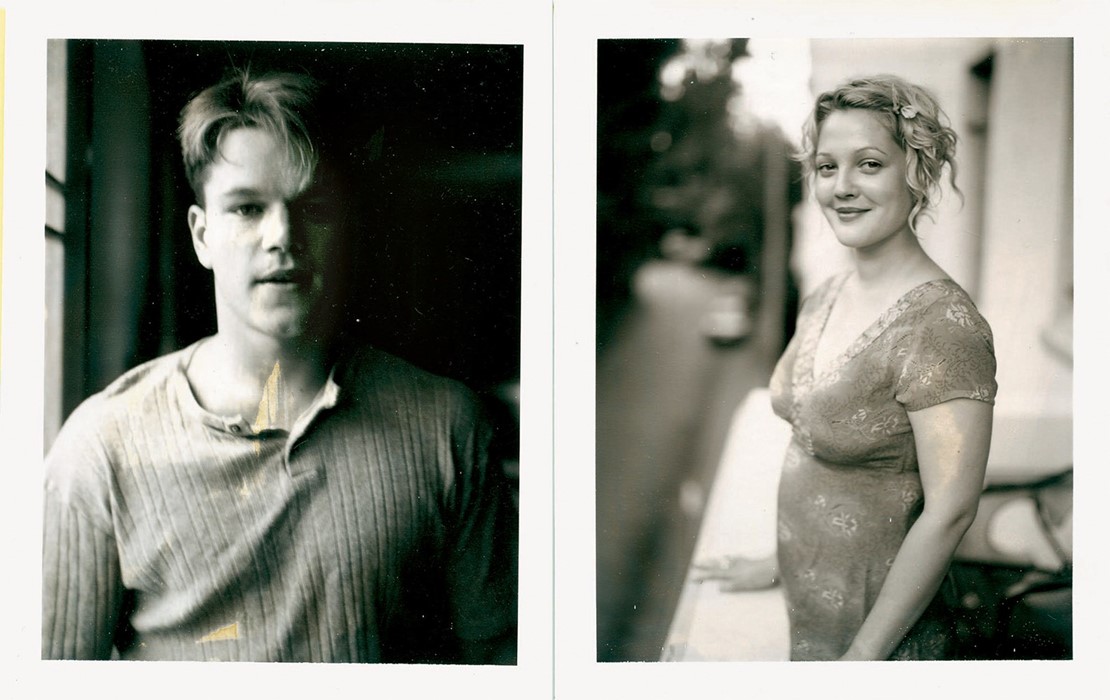

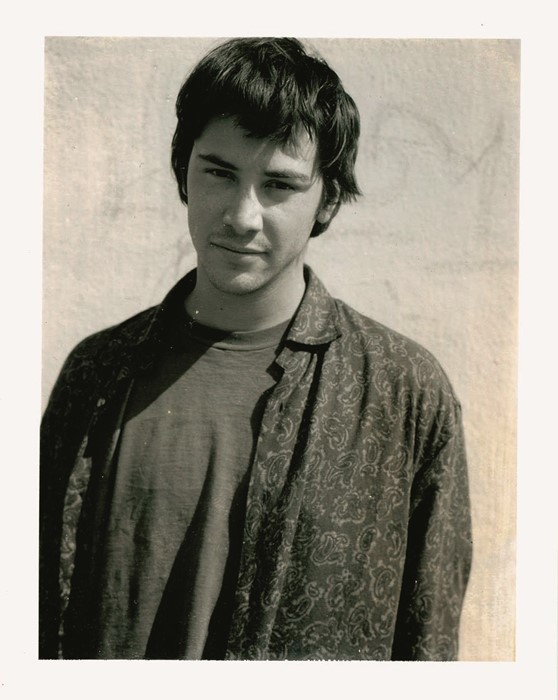

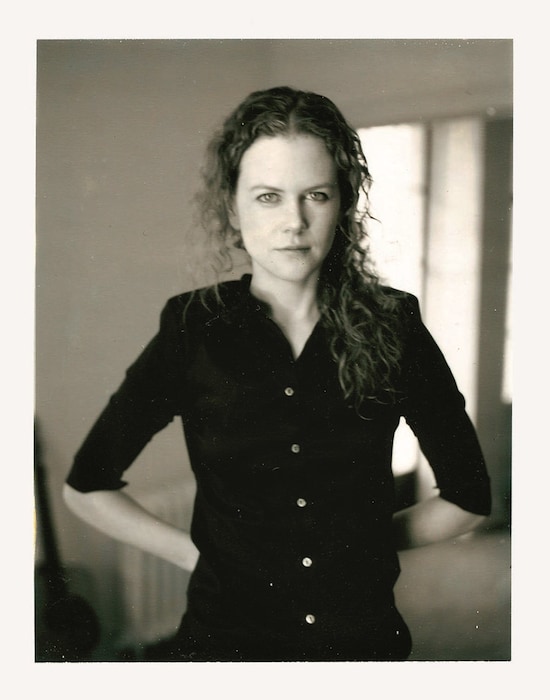

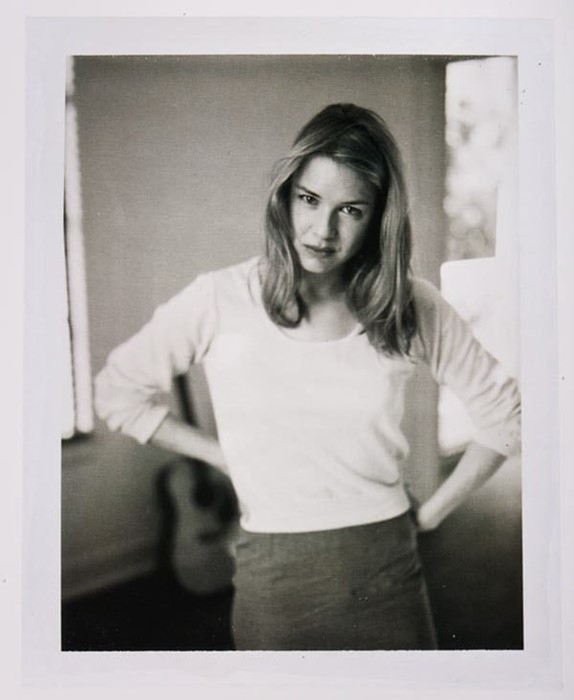

What? Fans of the director have long been fascinated with his idiosyncratic process, from the physical tools he uses to his inspirations and collaborators. Now a new book, published by La Cinémathèque Française with Actes Sud and released today, presents a welcome opportunity to step inside Van Sant's mind courtesy of expansive interviews, influential artworks, visually arresting moodboards, diagrams plotting out scenes, on-set photographs, and perhaps best of all, the many Polaroids the director took early in his career to document the stars who passed through his studio, which acted as a key casting tool in the days before digital photography.

The images, taken between 1983 and 1999, were captured on a "refurbished old Polaroid" camera that Van Sant bought in the mid-70s, shortly after completing his studies at at the Rhode Island School of Design. Unlike today's instant cameras, the device produced a small print and a negative, Van Sant explains in the book, and he would use these negatives "to be able to make different kinds of prints" – a fact he soon saw the benefit in exploiting. "With Drugstore Cowboy, all these different people would come in, like John Glover [and] the Chili Peppers members," he recalls. "People were coming in and I was thinking I should use the negative film." This proved no mean feat, however: "It was hard for me because I would meet ten people within a couple of hours, and then I’d have to go back to the bathroom – in a big building in Santa Monica that had thirty floors, an office building bathroom – and try and put [the negatives] in a pan and wash them and hang them up. I would hang them up in my office with clothes-pins because they had to drip dry. So it was a little bit of a pain in the ass, but I did it because I thought, now that I’m taking all these photos of all these different character actors and also sometimes bigger actors or musicians, then I’ll have a collection and I can have a show – like that was the whole point. But then meanwhile, I was using the photos themselves for casting."

Why? The resulting photographs are wonderfully remisniscent of Andy Warhol's earlier Screen Tests or Juergen Teller's later Go-Sees: documenting some of the world's most influential faces in a joyfully candid and unstaged manner. As the book's author Matthieu Orléan notes, "It matters little whether the actor got the part (Doug Cooeyate in Mala Noche; River Phoenix, Keanu Reeves and Udo Kier in My Own Private Idaho; Matt Dillon in Drugstore Cowboy; Nicole Kidman and Casey Affleck in To Die For; Matt Damon and Minnie Driver in Good Will Hunting), whether the location was chosen or not, whether the author did or didn't work on the screenplay: the magic power of the Polaroid is that it can show sublimation at work, witness the flowering of desire and reveal the timeless, immemorial forces that come to the rescue of the real world."

Gus Van Sant: Icons is out now, published by La Cinémathèque Française with Actes Sud.