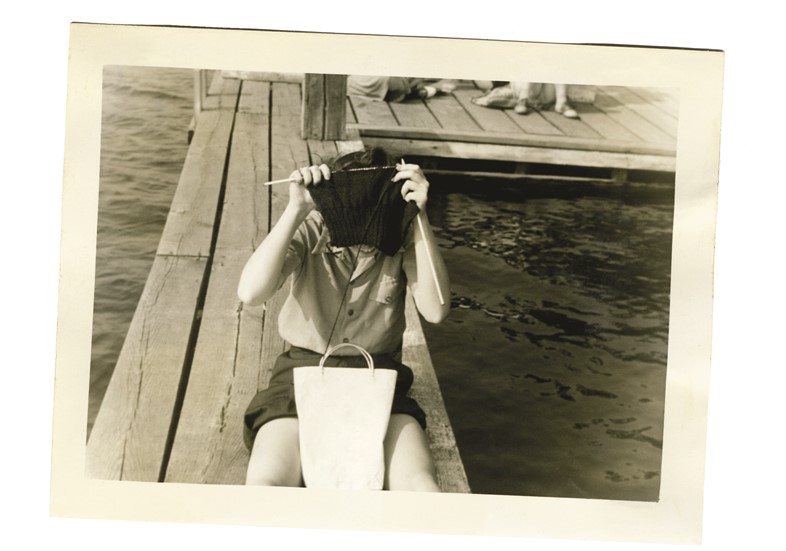

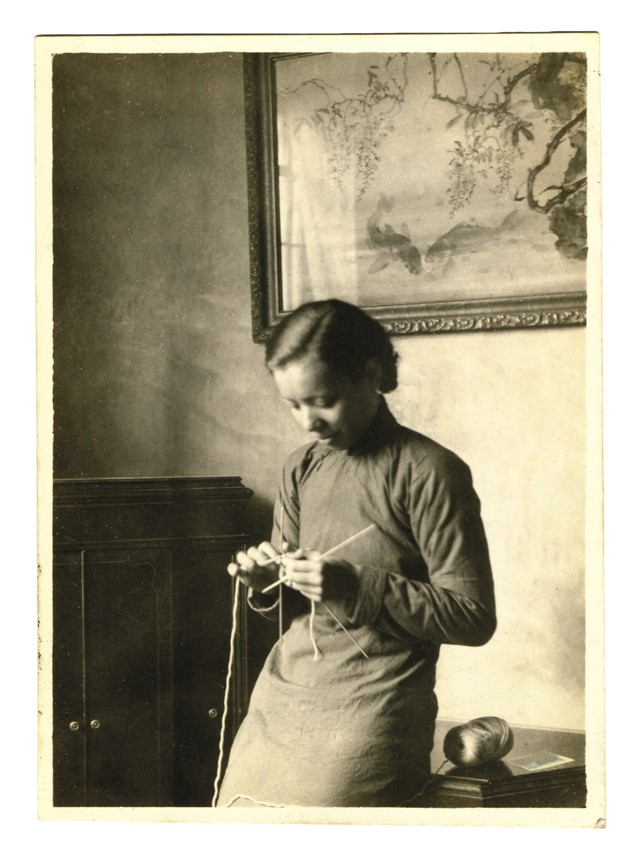

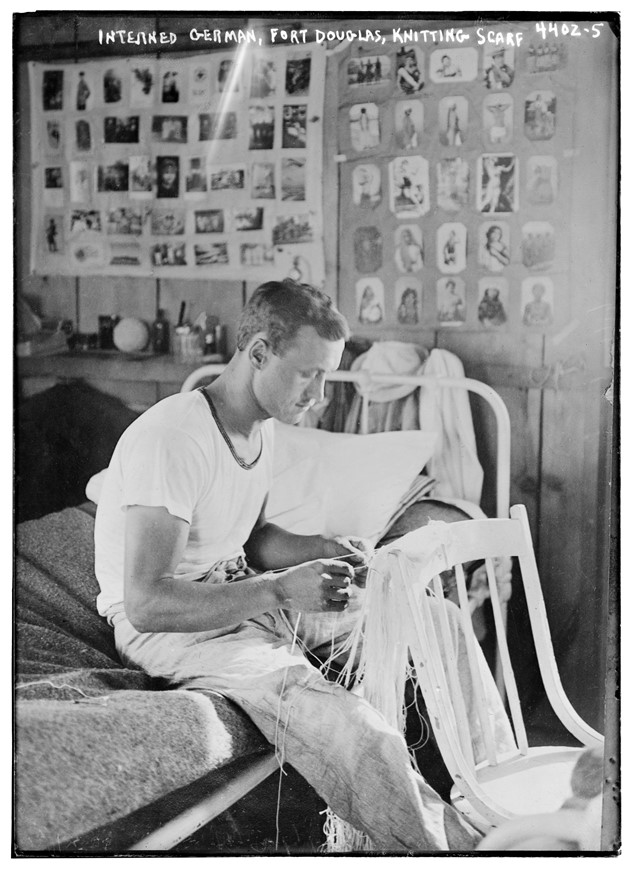

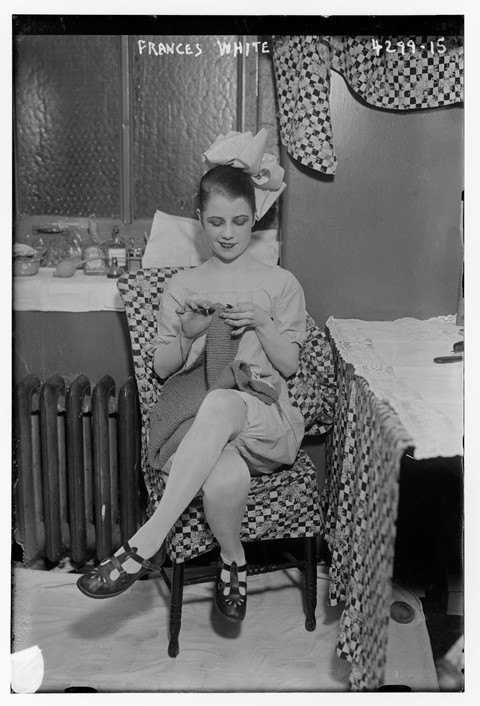

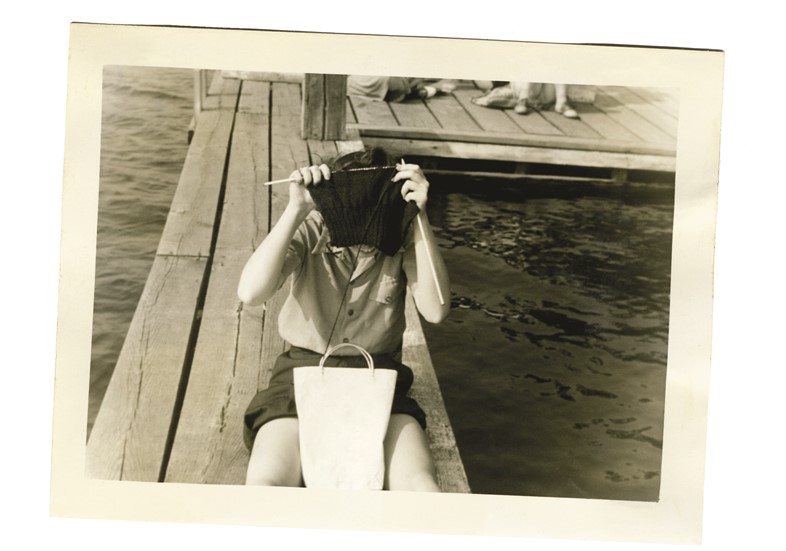

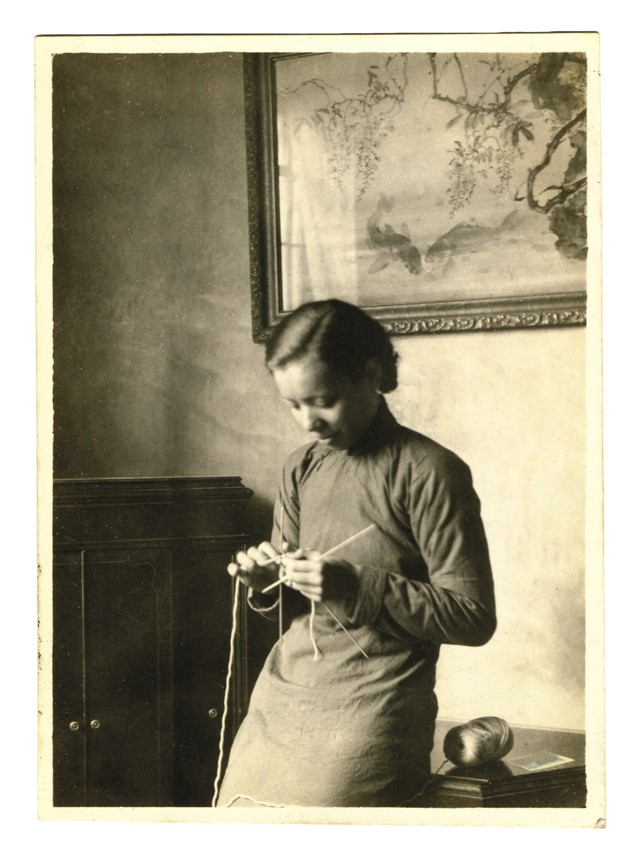

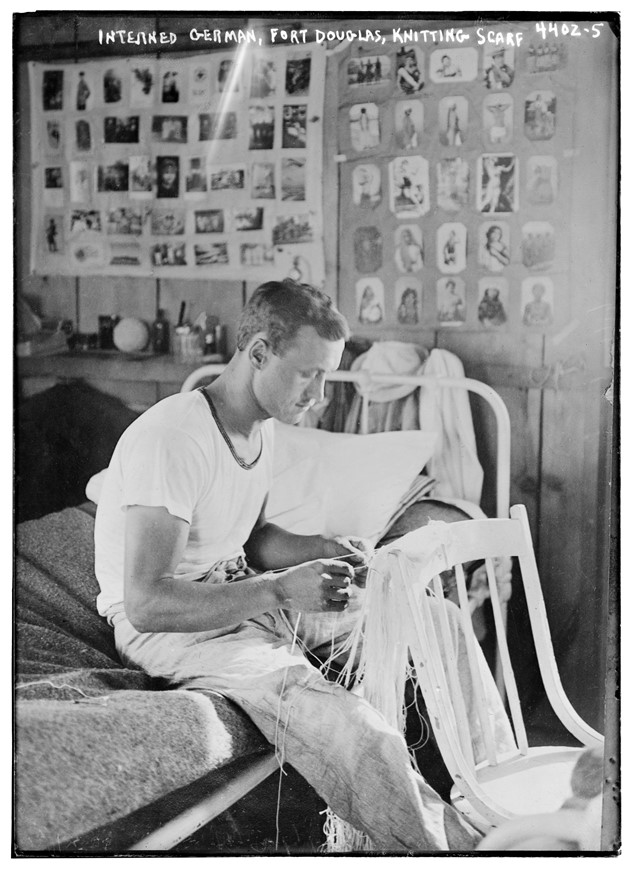

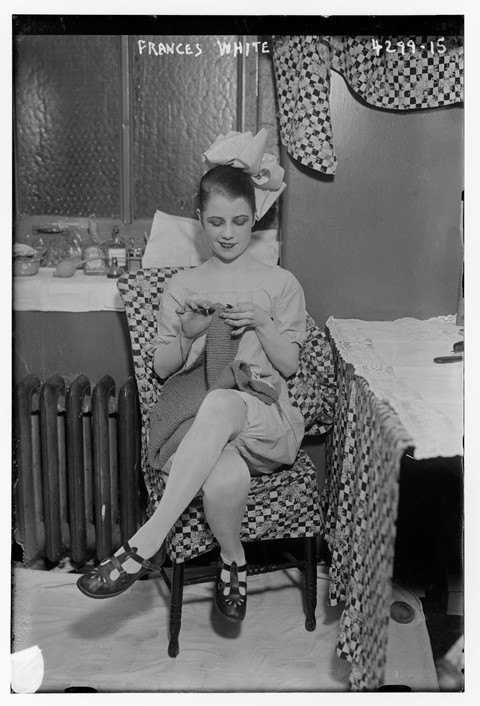

The habit of knitting will evoke personal memories for anybody who’s ever received a lovingly crafted but slightly out-of-shape Fair Isle Christmas jumper, or struggled to complete a wearable scarf. Collector, artist and curator Barbara Levine’s charming new photobook, People Knitting, evokes these individual memories via a beautiful collection of vintage vernacular photographs which invite the reader to speculate as to exactly what kind of person each of her subjects is. As Levine explains in the book's introduction: “To watch people knit is to be invited into their private world of contemplation and innermost creative expression, but at the same time, they are preoccupied – mapping out a pattern, counting a line, envisioning some future garment that you can’t imagine and may never see.”

The chronological anthology charts knitting’s transformation from a virtuous and essential household craft in the late 1800s, through patriotic demonstration of solidarity during wartime, to develop into a hobby enjoyed by movie stars and teenage girls alike in the 1950s and 60s. The photographs are punctuated by valuable lessons relating to the craft, whether it be Emily Post’s practical advice from the New York Times in 1943, “Do not wave long or shiny needles,” or Elizabeth Zimmermann’s more philosophical pearl of wisdom, “Properly practised, knitting soothes the troubled spirit, and it doesn’t hurt the untroubled spirit either.”

It is exactly this therapeutic effect which has caused knitting’s recent popularity to soar. No longer the reserve of grandmas in knitting circles, the pastime has enjoyed a revival, becoming one of the most popular activities for those seeking a mindful practice with the added bonus of a thoroughly individual scarf or blanket to show for it at the end. What’s more, the act of knitting can make a meaningful difference in the form of ‘craftism’ – a form of slow, gentle activism that you may have seen dubbed “yarn bombing” or “guerrilla knitting” – because nothing says “I care” like a hand-knitted protest blanket. Whether it be the London cabbies, the abolitionist Sojourner Truth or the Victorian dowagers that grace this book’s pages, Levine aptly demonstrates that knitting is a quiet and defiant form of revolution, albeit an infinitely wearable one.

Peopple Knitting: A Century of Photographs by Barbara Levine is out now, published by Princeton Architectural Press.