She lived with Djuna Barnes, photographed Man Ray, and taught Marcel Duchamp how to dance. Upon the release of a book showcasing her famous Paris Portraits, we discover the woman behind the camera

Who? Berenice Abbott is proof if any were needed that the power of a good haircut should never be underestimated. After graduating from Lincoln High School in Springfield Ohio, the young Abbott had a barber cut off the long, thick braid which hung down her back before starting at university in the autumn. The effect of such a drastic change was palpable; she notes how “my bobbed hair startled the campus”, and indeed it was this first stylistic step that would give Abbott her new and liberating identity. “A handful of students from New York at once mistook me for a ‘sophisticate’,” she writes. “We became friends, and a new life began for me.”

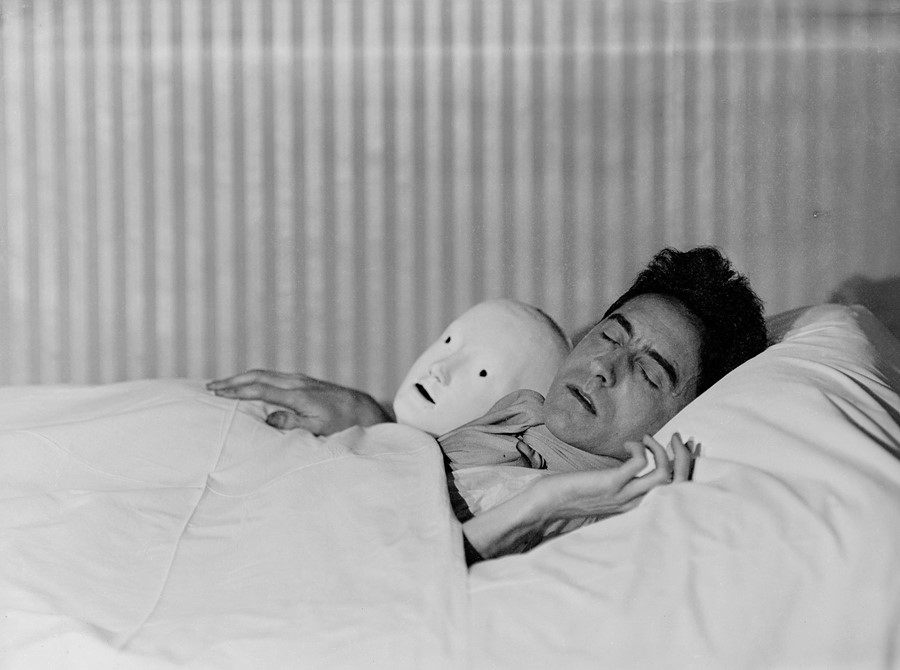

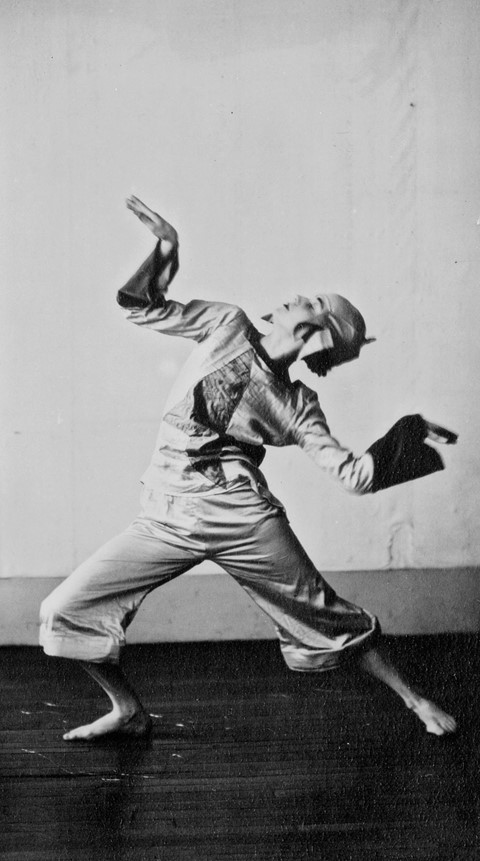

Abbott remembers vividly the “pull” of the Big Apple in 1918 and soon she threw herself from Ohio obscurity into the thriving creative centre of Greenwich Village, living with author Djuna Barnes and teaching Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray to dance. She was described, enchantingly, by the French writer Jean Cocteau (one of her many subjects) as being like “a chess game between light and shadow.” Abbott would go on to become one of the greatest and most intrepid female photographers of her time.

What? In the spring of 1921, Abbott was advised by her “Dada Baroness” friend Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven to go to Paris for inspiration, and she boarded a ferry to France, studying sculpture both there and in Berlin. While studying, Abbott became involved in Dadaist publications and took up jobs as a model to support herself, working with artists such as Nickolas Muray and her friend Man Ray. It was during her time in Paris that Abbott bumped into Man Ray on the street one day – by this time he had also relocated to the French capital – looking for a darkroom assistant who “understood nothing about photography”. Abbott fit the bill, and began work at once.

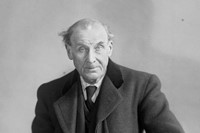

She “took to photography like a duck to water,” later declaring that “I never wanted to do anything else”. Following Man Ray’s lead, Abbott began a career in portraiture, shooting headshots for artists. One job naturally led to another, and with the encouragement of her new teacher and the generous funding of the art heiress Peggy Guggenheim – who also funded the work of her ex-roommate Barnes – Abbott’s confidence and success grew. Within a year her photographs were being exhibited to great acclaim; before long, like her tutor Man Ray, she was taking photographs of some of the most exciting and influential figures in Paris at the time, her benefactors including Guggenheim, Coco Chanel, Max Ernst, Andre Gide, Phillippe Soupault, Jean Cocteau and Marie Laurencin, to name but a few. Many of her portraits were first shown on the walls of Sylvia Beach’s now world-renowned English bookshop Shakespeare and Co. - Beach, of course, also being one of Abbott's subjects. With her growing reputation, the photograper was able to open her own studio, where she continued to work with artists and writers while developing her unique style.

This development saw her become rapidly enamoured with the work of French photographer Eugene Atget and his portraits documenting Paris not through its people, but through its streets. In 1929, determined to create the same kind of vision for New York, Abbott headed back to America to photograph the city that had first bewitched her at the age of 19. Now, in the first book of a series by Steidl which aims to explore Abbott’s entire oeuvre, the portraits that launched her career – 115 images of 83 subjects, to be exact – have been scanned from the original glass negatives and printed in full, creating a vivid depiction of pre-war Paris and those working within it.

Why? As Sylvia Beach noted in her memoirs: “To be ‘done’ by Man Ray and Berenice Abbott meant you were rated as somebody”. Although Abbott is now famed for her architectural images of New York’s changing skyline and her role in the development of scientific photography – she heralded the medium as the ‘spokesman’ for science, becoming the photographic editor of Science Illustrated in 1944 – her formative years remain rooted in the bohemian world of 1920s Paris.

Abbot was a pioneering force in photography throughout her life and one of the most influential female photographers working in a male-dominated profession. Unlike her mentor Man Ray, it is Abbott’s acute clarity that makes her photography so compelling. Rejecting experimental techniques such as distortion and double exposure, which were so fashionable at the time, Abbott opted for simplistic and naturalistic settings and poses. Her portraits highlighted a scientific rigour with which she would continue to approach subjects throughout her life; whether a human, a building, or the molecular structure of soap bubbles. “People say they have to express their emotions. I’m sick of that. Photography doesn’t teach you how to express your emotions; it teaches you how to see,” she proclaimed. Abbott’s vision was one of honesty, which becomes evident in her stripped back depiction of the artists represented in the book. We have her to thank for drawing back the curtain, generating so many intimate portraits of the creative figureheads living and working in Paris during the 1920s. We have her to thank for letting us see.

Berenice Abbott: Paris Portraits 1925-1930 is out now, published by Steidl.