As an exhibition of the photographer’s compelling shots on the set of cult film Performance go on show, we catch up with Beaton expert Joanna Ling to hear the scandalous tale behind their realisation

Mick Jagger in his 1960s and 70s heyday was one of the most photogenic human beings on earth; his unconventional beauty, electrifying ability to perform and inimitable style making him the ideal subject. Indeed, hundreds of beguiling images exist of the Rolling Stones frontman over the course of these golden years, but few capture his appeal so brilliantly as those taken by lauded British photographer Cecil Beaton. Now, a forthcoming exhibition at Sotheby’s S|2 gallery gives us a welcome chance to revisit one of Beaton’s most notable Jagger shoots, taken on the set of notorious British crime drama, Performance, filmed in 1968 and directed by Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg.

“Beaton was rarely awed by his sitters,” explains Joanna Ling, keeper of the Cecil Beaton Studio Archive, “but he was absolutely fascinated by Mick Jagger. A good indication of how Beaton felt about his sitters is how many images we have of them in the archive and whether they warrant their own box of negatives. Greta Garbo, who he was obsessed with for decades, has her own box, as does Audrey Hepburn, and Jagger.” The pair first met at the Boudin Ball in February 1966, where Beaton was immediately struck by Jagger’s charm, going on to note in his diary that the singer was “one of the most elusive people… like the Mona Lisa he knows everything, has seen everything.” The following year he chanced upon the Stones during a trip to Marrakech, a meeting which resulted in his first photographs of the singer, striking sultry poses in tight chequered swimming trunks next to a pool. “I was fascinated with the thin, concave lines of his body, legs, arms, mouth almost too large,” he wrote at the time. “He is beautiful and ugly, feminine and masculine.”

Over the next year Beaton photographed Jagger multiple times, striking up what Ling describes as a “mutual admiration” with the star, and inviting him to both his London and Wiltshire homes for sittings. Thus when he was invited to photograph on the set of what would be Jagger’s acting debut, Beaton jumped at the chance. “Mick was a big draw for him,” Ling tells us of Beaton’s involvement in the project, “but I think that that whole London scene also struck a chord with him because it was rather how he’d been in his youth in the 1920s and 30s, hanging around with the Bright Young Things. The two generations shared a lot of things in common – the same sort of decadence and rule breaking; breaking new boundaries.” If hedonism was what Beaton was seeking, it is certainly what he got: during the shooting of Performance co-director David Cammell encouraged the cast and crew to take drugs and forge sexual relationships to help create the required air of debauchery – and as a result it took two years for the heavily edited, yet still X-rated, version of the film to finally be released. Jagger and his compelling co-star Anita Pallenberg – the then-girlfriend of fellow Rolling Stone Keith Richards – are widely rumoured to have crossed a line during a supposedly simulated sex scene, much to Richards’ fury. “Marianne Faithfull [who was replaced by Pallenberg in the role of Pherber after becoming pregnant] wrote extensively about the film and called it a ‘psychosexual laboratory’ which sort of sums it up really,” says Ling. “But how much of it was myth and how much really happened is part of the enduring fascination of the film.”

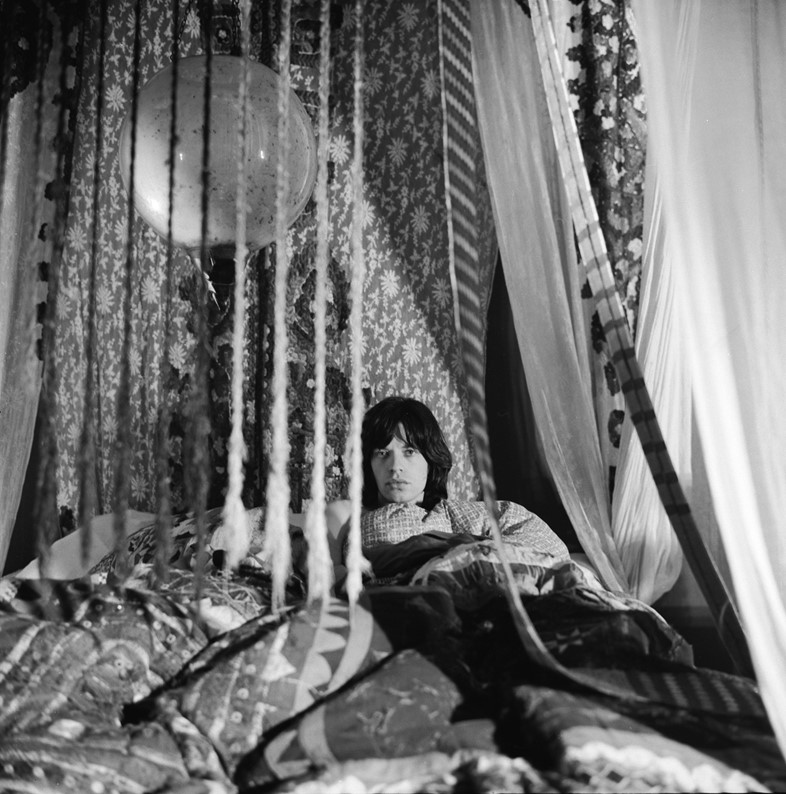

Beaton’s images are taken in the lavish house of Jagger’s character Turner – a former rock star who becomes embroiled with notorious east end criminal, Chas (played by James Fox) when he takes him in as a tenant. For Beaton, also an Oscar-winning costume designer and a set designer, the swathes of Moroccan fabric, jewel-hued walls and opulent furniture would have greatly appealed to his sensibilities, Ling explains. “The shoot is very much focused on Mick Jagger, but the whole set was clearly very important to him too.” This is evidenced by the ways in which the photographer skillfully frames his subjects within their surroundings – take the arresting image of Jagger dangling upside-down off the bed, for example, which sees his bent arms mirroring the diamond pattern of the fabric behind him; or the excellent shot of Pallenberg in a white dress and fur coat, engulfed by an elaborately carved and gilded chair, around whose curves Jagger has draped himself.

Beaton’s acute awareness of line, texture and colour is not the only defining element of the images however; equally remarkable is his capacity to bring out the best in his subjects. Jagger positively smoulders, while even Pallenberg – whom Beaton had previously described, with typical waspishness, as having a “dirty white face, dirty blackened eyes, dirty canary drops of hair, barbaric jewellery” – dazzles in front of his lens. In one shot, Beaton includes himself in the picture, capturing his own reflection as well as those of a reclining Jagger and Pallenberg in the mirrored ceiling above. This was a favourite trademark of his, Ling points out. “He often used this device when he was photographing people – appearing somewhere in the photograph in a mirror – and he did this from early on; when he photographed Adele Astaire in New York to Picasso to Warhol. There’s also a particular photo of Lord Mountbatten taken in Delhi in 1944 where they’re lying on sofas below this mirrored ceiling and it’s very reminiscent of that.”

In listing off just a few of Beaton’s esteemed, and very varied, sitters, Ling has touched upon another notable facet of the photographer’s oeuvre – his adept bridging of the establishment and the anti-establishment. “He had a foot in both camps,” she expands. “His assignment before this was photographing the Queen – the famous portrait of her in the cape – and it was very much a news story at the time that such a well-known and sanctioned photographer would be shooting on the set of such a forward, provocative film. But he took it totally in his stride; he was asked about the shoot and he just said, ‘It really is all part of a day’s work to me.’ The thing to remember about Beaton is that he was brilliant at changing with the times – he managed to capture the zeitgeist of each new era as it emerged, from the 20s onwards, and adapt his style accordingly. He was always an innovator and I think that the Performance shoot is the perfect example of that. It was a groundbreaking film and it symbolised the flamboyant bohemian life of London at the time, and Beaton was there to record it.”

Performance by Cecil Beaton is at Sotheby's S|2 from November 25 until December 23, 2016.