As the extraordinary provocateur's New York exhibition draws to a close, we take advantage of the welcome opportunity to look back on her formidable career thus far

Who? Ever since Carrie Mae Weems first picked up a camera, thanks to a 21st birthday gift from her then-boyfriend, she was convinced she would become a visual artist. That moment was 1976 New York, when the ramifications of the Civil Rights Movement was still being felt, and the Portland-born creative activist knew, as she has often recounted, that she would dedicate her lens to black women. 1976 was also the year when Weems made her first visits to the Studio Museum in Harlem, where a thriving avant-garde community of black intelligentsia and African American artists would motivate her now 30-odd-year career. But, as Weems is often at pains to make plain, black female subjectivity would only serve as the entry point to explore much wider concerns, from individual and collective memory to gender, class, race, and cultural identity.

If that makes for a rich and controversial well of issues, Weems’ penchant for humour and storytelling buoys her work with sharp-witted grace. In fact it was not only via studies in the fine arts that Weems eventually pursued her passion for visual storytelling; in 1984 she enrolled in a graduate program in Folklore at Berkley, California, where insights into realms like folk art and performance studies, ethnomusicology, and race and coloniality powerfully lent themselves to Weems’ picturing of narratives that spoke of personal and shared histories. From her early documentary photography to later staged images, performance, video and the use of written and spoken word, she has largely used herself as the subject, object, performer and director of her practice. Where cinema, art, history and popular culture lack black female protagonists, Weems effectively gives one centre stage.

What? You may know Weems for her 1990 Kitchen Table Series, the black and white photographs of the artist sitting alone at a kitchen table, or with various family members, children and lovers staging an array of domestic scenarios under the room’s glowing light. Inflected with cinematic overtones, it was this seminal series allegorising the micro peaks and troughs of familial relationships – or the macro power dynamics of social structures – which brought critical acclaim to the now 63-year-old artist. As Weems herself has said, “I think the reason that the work has been able to speak so broadly is it speaks to our deeper humanity, but [I used] the African American subject to get to that. In other words, getting rid of that stereotype so this person’s humanity shines through. That’s the project, that’s what I’m doing.”

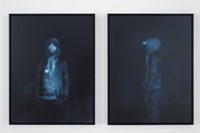

Proving that beauty and radicalism can come hand in hand, in more recent artworks, Weems borrows from the lexicon of canonical art history. While in Blue Notes (2014), she overlays images of artists and singers like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Claudia Lennear with modernist coloured blocks, in the 2010 Untitled (Colored People Grid) Weems arranges portraits of black children in a Sol Le Witt-like grid – each time inserting the spectre of the Other into the artistic canon as we know, in order to rewrite the books. The telling configuration of a grid also makes an appearance in earlier works that rebuke a colonial tendency to categorise, classify and stereotype. Such rebukes, though, don’t always relinquish her canny sense of humour, as in the 1987 photo-text Black Woman with Chicken.

Why? It’s easy to see why Weems, who was the subject of a 2014 Guggenheim retrospective, is so relentless in her artistic focus. As she recently said in an indelible interview for Lenny, “I realised at a certain moment that I could not count on white men to construct images of myself that I would find appealing or useful or meaningful or complex”. Just as art history has traditionally failed to recognise the creative contributions of non-white communities and the issues they face, Weems is ever-conscious that cinema also lags behind. “I love Fellini. I love Woody Allen. I love the Coen brothers, but they’re not interested in my black ass”, she says. “We don't even occur to them as subjects. (…) I can't count on them to do my job. I can't count on them to think about me in any sort of serious way (...) I look at it as unrequited love. You know? I love them, but they ain’t thinking about me. It’s not really a complaint. It’s just the reality. I build a form for myself that don’t exist anyplace else.”

Carrie Mae Weems is on show at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, until December 10, 2016.