Some 50 years after it was first written, a new publication by Taschen re-examines Tom Wolfe's seminal The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, the book which heralded a new era for hippie America

Few have so poetically, energetically and zealously delineated the experience of an acid trip as Tom Wolfe. He describes this “beautiful discovery” as “to actually see the atmosphere you have lived in for years for the first time and to feel that it is inside of you, too, flowing up from the heart, the torso, into the brain, an electric fountain…” at one moment in his seminal 1968 book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Ostensibly the book documents a community of of wild hippie types, travelling America together in the psychedelic haze of a brightly patterned school bus with their appointed guru of sorts, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey (“Hipster Christ,” in Wolfe’s words) following his release from jail. What it really does is document the hearts and minds of not just this strange troupe, but of a seismic moment in American cultural and lysergic history.

While perhaps Timothy Leary has become more famed for his LSD experiments at the time (who hasn’t heard the phrase he coined, “Turn on, tune in, drop out”?) his examinations came from the perspective of a curious academic. Wolfe, Kesey and their gang however took on a far more communal and social approach, continuously gathering hedonistic companions and lovers as they took on a journey across America’s cities, their minds, and their shared consciousnesses.

A stunning new letterpress edition of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test has recently been published by Taschen in a run of just 1,968 copies signed by Wolfe (a nod to the original publication date), containing reproductions of Wolfe’s manuscript pages, Kesey’s jailhouse journals, and underground magazines of the period; as well as photographic essays by Lawrence Schiller and Ted Streshinsky, who Wolfe worked with on stories about the psychedelic counterculture for Life magazine and the New York Herald Tribune respectively.

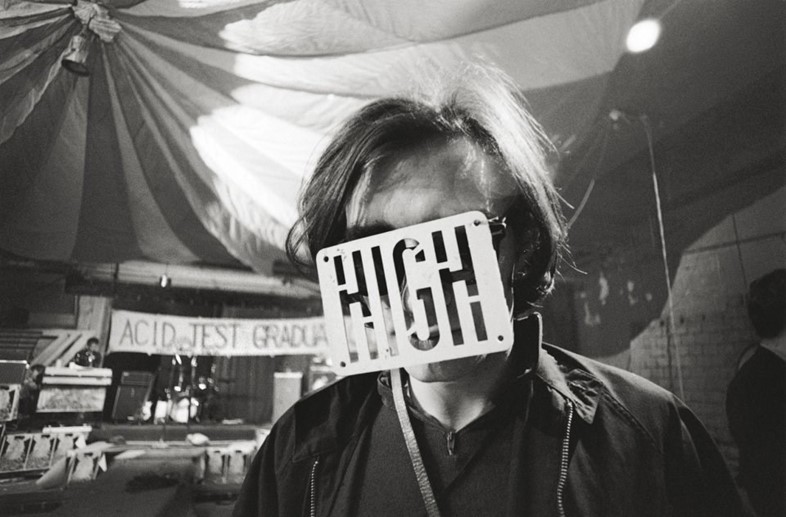

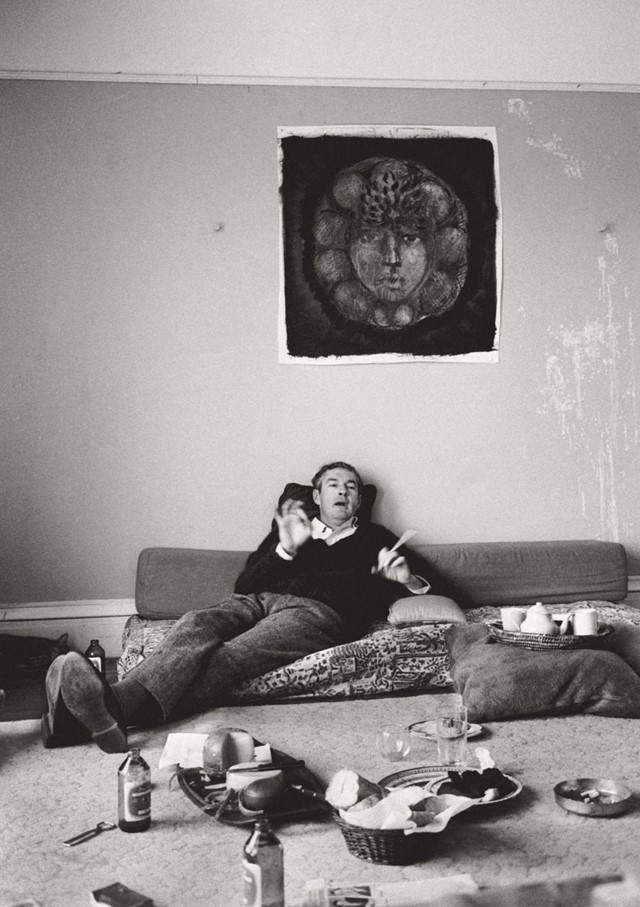

While some images show intense and intimate portraits of those undergoing the “Acid Test” (or: taking LSD), often shot in their homes, others paint broader pictures of the scene of the day – the “thing,” in Wolfe’s words – the dropping out and freaking out and forging new ways of living and relating to the world. This was a contrast to American ideas of Individualism, instead focusing on community and freedom from constraints of traditional relationships, jobs, and even time itself, as the book notes – there were days and weeks when the members of the Merry Pranksters, as the group was known, had no idea what time it was, let alone what day of the week.

During this late 1960s era, these small movements of rag-tag folk looking for something “Further”, as the bus was named, mirrored wider changes to American society. Whether or not you were hanging around with famous writers and dropping acid, the mood was shifting from that of buttoned up 1950s primness to something wilder. This was evidenced across fashion – free-flowing fabrics and flowers replaced neat dresses and crisp blowdries – in art, and in the music that soundtracked the time: the Beatles’ nods to eastern mysticism; Janis Joplin, whose photograph features in the new book; and of course The Grateful Dead, who spearheaded the wild sonic freakouts of late 60s San Francisco.

The ideologies of the hippies dissipated over time, yet a countercultural itching to shake off the shackles of societal norms has never really left the core of youth movements, from punk to the rave scene. “They were… well, Beautiful People!” writes Wolfe. “Not ‘students,’ ‘clerks’, ‘salesgirls,’ ‘executive trainees’… we are Beautiful People, ascendent from your robot junkyard.”

Tom Wolfe: The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is available now, published by Taschen.