Ahead of its premiere at London's Tate Modern, we speak to filmmaker Pierre Bismuth about his masterful new doc, following his ten-year hunt for a mysterious "lost" artwork by the famous American artist

At the end of the 1970s, celebrated American artist and pop art pioneer Ed Ruscha painstakingly created a vast fake rock out of fibreglass, covered it in the dust of real desert rocks so that it would precisely resemble them, and playfully dubbed it Rocky II (it was his second attempt at creating the sculpture) in reference to the Sylvester Stallone franchise. He then drove it out into the Mojave desert and placed it, perfectly disguised, in a secret location. Its making and depositing was captured on camera by a BBC film crew, and went on to appear in a short documentary about Ruscha that aired in 1980. And yet, from that point onwards, the prolific artist has never mentioned the installation again, and no record of it exists in his extensive catalogue of artworks.

Around 26 years later, French artist and filmmaker Pierre Bismuth – who is also the man behind the original storyline of Michel Gondry’s 2004 movie, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – stumbled across a VHS copy of the documentary which had accidentally been left at his house by a guest. Unbeknownst to Bismuth at the time, the 28-minute-long film would prove the catalyst for a new project that would occupy him for the next ten years of his life, resulting in his brilliant new documentary – or what he dubs “fake fiction” film – titled Where is Rocky II? “For a while after watching the documentary, I didn’t really think more of Rocky II,” Bismuth tells us over the phone from his home in Brussels. “But after a while I became curious about this work that I didn’t know, and it was only by trying to get a bit more information about it that I realised that no one else seemed to know anything about the piece, or the documentary, either.”

Bismuth had a friend who was closely acquainted with Ruscha, and so asked him to do a spot of sleuthing in his behalf, “but he couldn’t get any information,” he expands, “he said that Ed was just kind of silent about it”. By this stage, Bismuth’s curiosity was well and truly piqued: “I couldn’t understand why you would make an artwork to be totally invisible,” he explains, “or why you would allow the footage of you working on it to be shown in a major broadcast but then be completely silent about its existence! Rather than quitting my search it became even more important, and I started to think that it would be a great opportunity to do a film.”

As anyone familiar with his art, or indeed Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, will know, Bismuth’s creative approach is highly conceptual, intellectual and above all original, and his vision for Where is Rocky II? proved no exception. “My idea was to reverse the principal of Ed Ruscha’s piece: Rocky II being a fake rock, hidden in reality. I knew I wanted to make a documentary and because documentaries are based on reality, I wondered, would it be possible to hide reality within fiction? And, if so, how would you do it? My first thought was to make a film that avoided all the stylistic elements of a classic documentary, like the handheld, commando-esque filming, which creates an awareness of the presence of the camera. I felt that if you tried to hide the camera and make it appear as if what you were filming was fictional instead, that that would make for an interesting project. So the film was intended purely as the mirror image of Rocky II.”

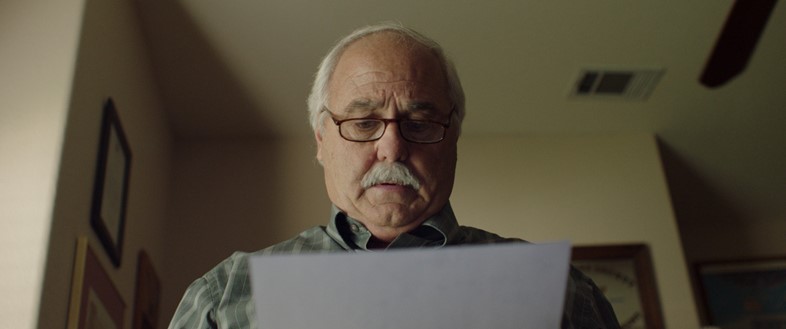

Concept in place, Bismuth’s first step was to go to London to capture some live footage of Rusha himself. “I knew that I needed him to start the film,” he says, “and in 2009, he had a show at the Hayward Gallery and was giving a press conference. So I went to it, posing as a journalist, and asked the question, ‘Where is Rocky II?’ and I was lucky that I got a reaction.” This enigmatic brief encounter forms the film’s brilliantly funny introduction, set to a suspenseful score, and was integral in driving Bismuth forward on his mission to unearth Rocky II’s whereabouts. The next decision he made, before embarking upon the hunt proper, was to hire a private detective. “I thought it would be me doing the searching initially but I really dislike being on camera so I decided to replace myself with somebody else. In Los Angeles private investigators are very common, and I thought, that’s the kind of person I need: someone who can appear on camera instead of me and who knows LA and the desert and can help me to navigate it.” Enter: Michael Scott, a wonderfully “square”, and very likeable former homicide detective, round-faced and silver-moustached, whom Bismuth selected for his “cool, non judgemental approach”. “I could just tell that he would accomplish his contract without wondering if it was serious or not.”

But while in Scott he had found his Hercule Poirot, the director decided that he also wanted somebody to represent himself in the more theoretic side of the investigation. “I felt that I was still too present in the film and I didn’t want to be. I needed somebody who would raise the question that I was interested in, namely why the artist was doing such a thing, and I very quickly realised that the best people to answer that would be screenwriters.” As a result, he drafted in DV DeVincentis, of High Fidelity and Grosse Point Blank fame, and Anthony Peckham, the writer behind Clint Eastwood’s Invictus and Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes, whom he invited to create a short film based around the story of the missing art installation. (In the finished film, Bismuth weaves the short into the documentary footage of Scott’s search, alongside clips of the writers’ high-energy brainstorming and writing sessions, to very clever effect.) “And that was it,” the filmmaker says with a chuckle, “the structure was established. And when you have a detective, a fake rock and some screenwriters, all that needs to be done is to watch it unfold.”

And that’s very much what Bismuth did, leaving it up to his protagonists to set the narrative wheels in motion. “It was an absolute lack of control, in a good way,” he says of his taking-each-day-as-it-comes approach. “It was just about adapting as fast as possible to the contingency – that was the key.” Scott’s search takes him from London deep into the California hills as he tracks down a wonderful array characters linked to Ruscha and the BBC film – most notable among these is the brilliantly laid back, perpetually pot-smoking artist Jim Ganzer, who describes himself as the “laziest person in the world”, and who Bismarck later discovered partially inspired the legendary Coen brothers character, the Dude (played to laconic perfection by Jeff Bridges) from The Big Lebowski. “When I saw Jim I thought, 'God, thank you; this guy is so amazing!'” Bismuth enthuses. As a close friend of Ruscha’s, Ganzer had been brought in to help create the fibreglass structure of the rock back in the 70s, and was credited as the “rock specialist” in the BBC film. He proves integral in speeding up Bismuth’s and Scott’s quest, forging a heartwarming rapport with the detective along the way – “That love story really happened,” chips in Bismuth with obvious delight – and accompanying him on his voyage.

Meanwhile DeVincentis and Peckham call upon the expertise of Mike White – the effervescent writer, director and actor who scribed School of Rock – who encourages them to take (the ADHD medication) Adderall to aid them in their plotting of a cinematic climax. The audience watches as both parties hurtle headlong towards their end goal, the interlinked real and fictional narratives working in perfect harmony, holding you in their thrall until the very last shot. So does Bismuth feel content with the way the improvised contingency plan unfolded? “I have no desire to do more than I’ve done,” he says with passionate conviction. “We answered all the questions we had – the whys and the hows – and it became about so much more than finding the rock; we ended up with all those fantastic characters. The rock is important but it’s also a pretext for having all these stories going on.” Last but not least, what does Ed Ruscha make of this filmic investigation into his enigmatic past? “He saw it in the summer at a special screening, but I haven’t had the chance to speak to him about it. His studio booked 30 seats for the premiere at LACMA in January though, so I’m taking that as a good sign.” As for whether Bismuth found Rocky II, and the hows and whys, as the filmmaker puts it, you’ll just have to watch for yourself.

Where is Rocky II? will screen at Tate Modern on December 9, 2016, followed by a special Q&A with Pierre Bismuth. Click here for tickets.