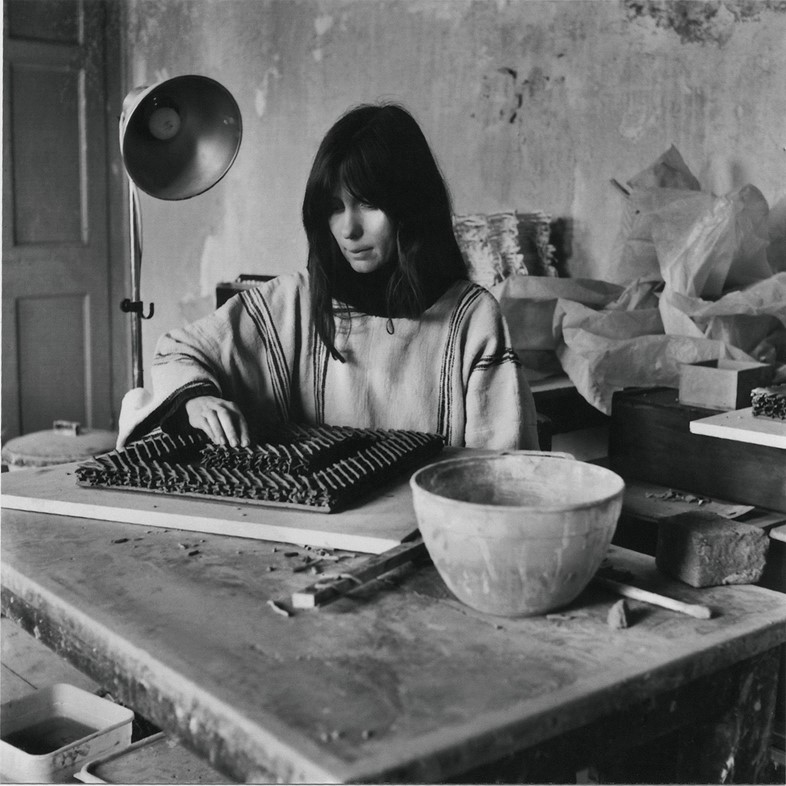

Gillian Lowndes' radical application of found objects singles her out as one of her medium’s most daring practitioners, and yet her legacy has been largely left in the dark, until now

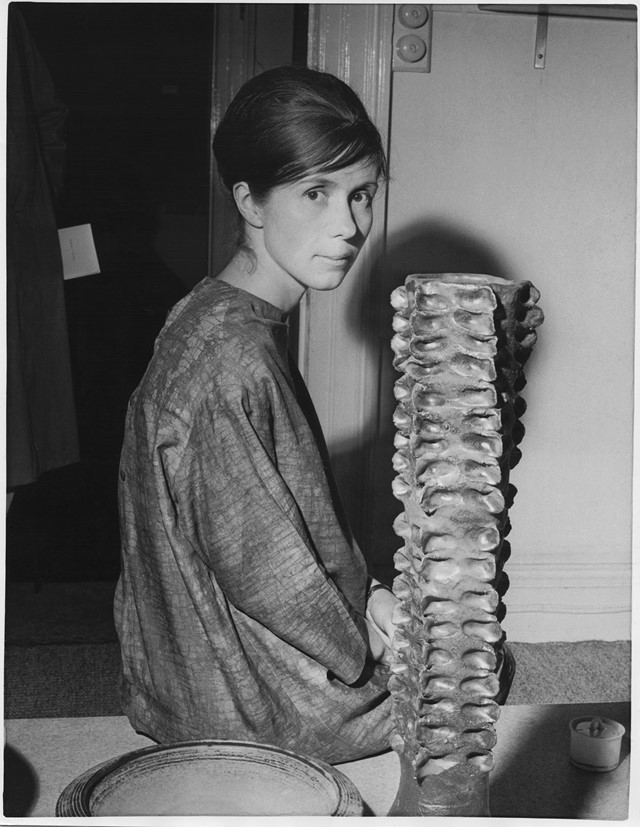

Who? Historically, the field of ceramics art has been unfairly labelled as a fusty, crafty pastime – one inferior to its more cerebral siblings in sculpture and painting, and founded on the practical uses of pottery rather than museum-worthy artwork. This all changed, however, with Gillian Lowndes. Born in Cheshire in 1936, the British sculptor began her career in comparatively traditional fashion, studying at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London and for a year at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris in the 1950s. Switching from Art to Ceramics midway through her studies, she worked primarily in clay, using coiling and slabbing techniques to develop her sculptural forms.

It wasn’t until she spent a year and a half in Nigera with her partner Ian Auld, in fact, that she began to develop the radical, experimental techniques which she has since become famous for. Living with Nigeria’s Yoruba people, Lowndes was exposed to tribal art the likes of which she had never seen before, which combined materials, textures and surface decoration with a vivacity that she found irresistible. “Following her return to the UK, Lowndes began experimenting, dipping fibreglass sheets into slip and porcelain, draping this over wire skeletons, creating delicate yet visually intense sculptural forms,” writes the Centre of Ceramic Art. “She started breaking up fired ceramics, attaching pieces together, assembling montages of her own work.” This radical and quietly assured new direction helped Lowndes to establish herself as one of the most daring voices of her generation in the world of ceramics, and she maintained this role, teaching, making and exhibiting her own work until her death in 2010.

What? Lowndes’ experimental methods have posed a challenge to the world of ceramics ever since she first developed her controversial methods on return from Nigeria in the 1970s – not least through her innovative destruction and then use of found objects to create her sculptures, ranging from bricks, wire and kitchen utensils (which she would often heat to immense temperatures before incorporating their remains in her work) to bulldog clips, can openers and pliers. “The found materials [Lowndes employs] are poor, low-status ones,” Tanya Harrod wrote in the January issue of Transcending Clay Crafts; “old bricks, clinker, granite clippings, mild steel strip, cheap industrially made cups and tiles”. This presented a challenge to the stubborn orthodoxy of ceramic sculpture, which was ill at ease with Lowndes’ willingness to straddle the worlds of high and low art, and to draw attention to residual markers of the working and upper classes. This, however, was exactly her point. “It is the methods and materials that produce the ideas, not the other way round,” she told the British Council. She continued in her experiments unhindered.

The rich visual language which resulted from such a democratic approach to her materials attracted an impressive following to Lowndes’ work: many of her pieces made their way into private collections thanks to her representation by Primavera Gallery; the V&A acquired pieces from the 1960s onwards; she had a major solo exhibition with the Crafts Council in 1987 and took part in a groundbreaking exhibition entitled The Raw and the Cooked in 1993. Not only was Lowndes comfortable occupying the liminal space between fine art and ‘working class’ craftsmanship, she positively revelled in it, maintaining a defiant modesty which she is remembered for to this day.

Why? In spite of Lowndes’ radical legacy her work has gone largely uncelebrated in recent years, tucked away in private collections. This winter, however, a retrospective exhibition at London gallery The Sunday Painter – the largest presentation of her works for more than 20 years – is returning her to her well-deserved place in the limelight. “Lowndes operated on the border territory between fine art and craft, and is renowned for her sensitive investigations of material and process, of serendipity and sculptural form,” the gallery explains. “Pigeonholed by the craft establishment of the time, her work predated the expanded ceramics field of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, while her pioneering transformation of clay and found objects places her firmly in the language and discourse of sculpture, a critical context that remained closed to her in her lifetime.” Now, at last, Lowndes is receiving her dues.

Gillian Lowndes’ work is on display at The Sunday Painter until December 23, 2016.