16 years after its original release, Lauren Greenfield's seminal study of womanhood and capitalism is as powerful as ever

“As disgusting as it may sound, when I have my Prada bag, my shoes, and my cell phone, I feel superior,” says Stephanie, a 14-year-old from Long Island. “Me and my friends walk around the mall with our heads up, like we’re hot shit. Just because of materialistic possessions.” Stephanie is at one of America’s many “fat camps” for adolescents, where teens spend their summer trying to shed pounds and, according to her accounts, hooking up with each other. Her eye-searing candor is just one of the disquieting interviews that appears in Lauren Greenfield’s re-released Girl Culture, alongside a collection of more than 100 photographs Greenfield shot of girls and women across America, originally published in 2002.

A lot has changed in the 16 years which have elapsed since the book's original publication; the fashion, for starters. Greenfield captures what was perhaps the last decade in which teen fashion still looked like teen fashion: khakis, spaghetti straps and belly tops, a style promoted by early 00s idols like Christina Aguilera and Britney Spears, their toned abs prompting abundant fitness fads. There are some unexpected portraits of a few of the icons of the day too, nestled among Greenfield’s shots – an 18-year-old Jessica Alba, still a fledgling TV star, pink-haired Gwen Stefani, smiling with braces, and a fresh-faced J-Lo, all appear. It was the beginning of a healthier, slightly more diverse representation of women in the mainstream.

But this isn’t an easy depiction of what it means to be a woman. In many ways, Greenfield’s book is a visual document of precisely what Naomi Wolf wrote about in The Beauty Myth (1990), revealing how deeply connected womanhood is with commercial industry in the U.S. Greenfield, a seasoned professional photographer who has worked for major magazines and newspapers for decades, uses her camera to “deconstruct the illusion,” as she writes in her afterword; in the process, she shows us how huge the industry around being a woman is, and how deeply conditioned women are to participate in it. Greenfield visits women all over the US – from coming-of-age ceremonies in the Hispanic community in Huntingdon Park, California, to exotic dancers in Nevada and May Day debutantes in Chattanooga, Tennessee – but they universally share the expectation that as women, they have to be young and beautiful in order to lead a successful life.

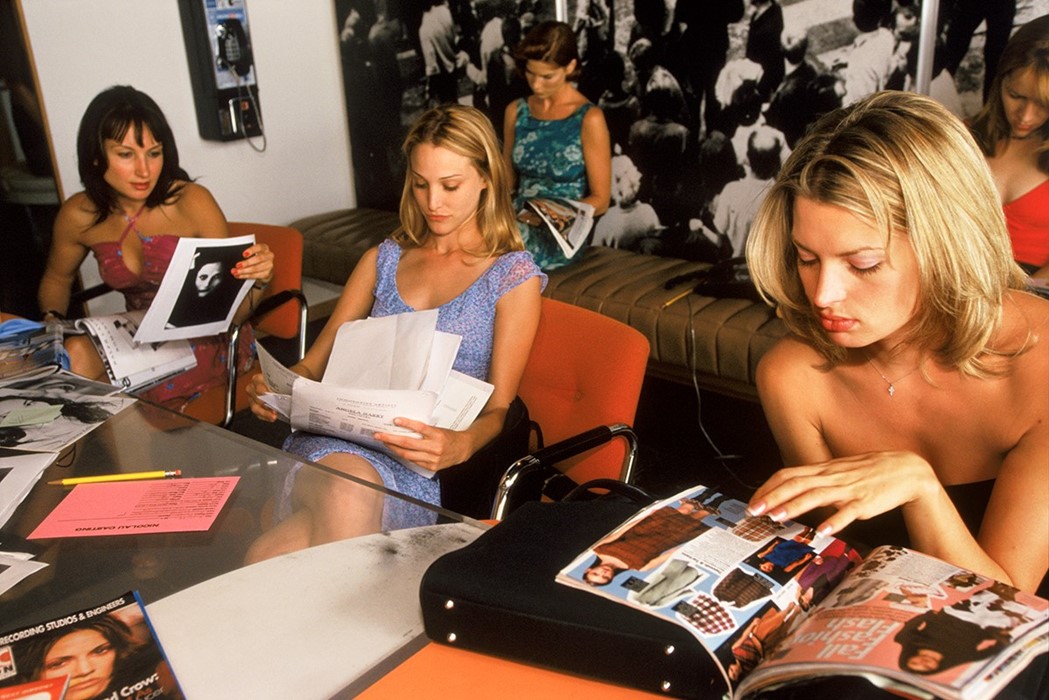

At times, Greenfield uses explicitly competitive environments to illustrate this: fitness and modeling competitions, pageants and Hollywood audition rooms. Other subjects are involved in the industry of female competition in other ways: pornstars, Vegas showgirls, playmates and shop girls at high-end fashion boutiques. Money is not the only cost. Between these scenes, Greenfield shows us teenagers at eating disorder clinics and weight loss camps, girls as young as 13, their lives derailed by this industry that relies on keeping women in constant competition. Through these pictures and texts, however, the industry emerges as multi-faceted and complicated, so bound up with our capitalist ideology that there’s no straightforward way to break free from it. Looking at the commerce which surrounds women as 2017 begins, it’s just as tough to circumnavigate the demands of capitalism. Advertising now infiltrates our feeds and targets our inboxes, but the messages, however tailored, still persuade us that we need to spend.

“I don’t think my modeling is good for society,” writes 19-year-old New Yorker, Sara. “I’m making a bunch of little girls feel bad about their bodies and go anorexic. I don’t think I’m doing the world any good. But if a client is offering you ten thousand dollars to do a shoot for the day, are you going to say no? You kind of have to have your own self-interest at heart.” Coupled with her some of subjects’ unflinching reflections on what it means to be a woman, Greenfield’s insights into American girl culture are shocking, at times unsettling and bleak, and they’ve lost none of their force today. The book was first published before the widespread birth of the internet, and is an example of the potential women have for using their image to express their own agency and truth. 16 years on, the trends may have changed, but many women are now following Greenfield’s lead in creating the world they believe needs to be exposed.

Girl Culture by Lauren Greenfield, with an introduction by Joan Jacobs Brumberg, is out now published by Chronicle Books.