Sculpture is shaking off its lingering air of old-school machismo, writes Laura Allsop. Here she highlights four of the artists playing crucial roles in its dynamic reawakening

If the recent Hepworth Sculpture and Turner Prizes — both won by assemblage wunderkind Helen Marten — are anything to go by, the various disciplines of sculpture are being put at the service of radical new visions. That both prizes showcased the work of exciting female artists producing often large-scale and densely layered work makes it an especially interesting time for a medium still shaking off a lingering air of old-school machismo. The artists selected here, all at different stages in their careers, and with disparate yet fascinating approaches to sculpture, are reaping plaudits, major museum shows and, in the case of Phyllida Barlow, a much-anticipated Venice Biennale outing this year. If anything could be said to link their practices, it is an interest in excavation, be it intellectual, emotional or material. Here, we take a whistle-stop tour of their work.

Phyllida Barlow

At 72, Phyllida Barlow is about to enjoy what many would see as the high-point of any artist’s career: this summer, she will be representing Britain at the Venice Biennale. Though she has been producing work for decades, Barlow stepped into the limelight only relatively recently, after retiring from her teaching post at the Slade School of Fine Art, where she taught many outstanding students including Rachel Whiteread and Martin Creed. Since leaving, she has earned a solo show at the Serpentine, representation at blue chip gallery Hauser & Wirth, a Tate Britain Duveen Commission, and selection to the British Pavilion, among other achievements. The work is rough-hewn, monumental in scale, suggestive of heavy industrial architecture and primeval formations, whilst being materially light and recyclable. Her colossal screestage, on view as part of the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture, is awe-inspiring, like a landslide poised mid-cascade, or a pier about to tip into the sea.

Daphne Wright

As curator Josephine Lanyon recently put it, Irish artist Daphne Wright grew up alongside and studied with the YBAs, but was never one of them. For over 20 years she has been quietly producing often large-scale and lyrical sculptural works engaged with domestic themes, in a tradition that inevitably calls to mind the late Louise Bourgeois. Late last year, she commanded a major show at the Arnolfini in Bristol, which included, among many arresting sights, a stallion contorted painfully on the floor as though toppled from its plinth. The work is beautiful, seemingly classical — the fabular creatures, the sublime expanses of Hellenic white — but cut with something darker, addressing uncomfortable subjects like dementia and aging. A plaster cast of floral wallpaper looks pleasingly decorative from afar, but up close, reveals small hearts suspended among the flowers, while from a speaker a woman’s voice issues unsettling cuckoo calls. Delicate yet visceral, Wright’s work is deservedly getting its dues.

Helen Marten

Helen Marten had a extraordinary autumn in 2016: in addition to a well-reviewed Serpentine solo show, she also claimed the inaugural Hepworth Prize for Sculpture and the Turner Prize. Aged just 31, she is comfortably ruling the roost, but with demonstrable humility and grace (she famously pledged to share the winnings for both prizes with her fellow nominees). The work is fiendishly difficult to parse, but so weird and beautiful as to cast a spell on the viewer. Sundry items appear like looking-glass versions of real-world domestic, architectural and industrial objects, from a teapot to a half-submerged fish, or a doll’s house to a chimney pot, arranged in mysterious yet rigorous tableaux underpinned by months of intense research. The work – which seems ready-made but is almost all fabricated – could be read as a reflection of the surfeit of information currently available at our fingertips, a diagram of a philosophical idea, or a simple invitation to fall down the rabbit hole, where delights both visual and cerebral await.

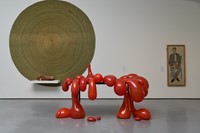

Anthea Hamilton

Any discussion of 2016’s Turner Prize will invariably include a mention of the enormous butt that formed part of Anthea Hamilton’s showcase. A seemingly grandiose recreation of a drawing for a doorway by the Italian designer and architect Gaetano Pesce, the parted buttocks were repeatedly described as golden, though Hamilton has pointed out that they, in fact, belong to an Asian male. Her work is subtly political, engaged with different kinds of bodies and their possible encasements — from a lichen-decorated platform boot, to a recreation Moschino suit in woven brick pattern that recalls the urban environment around the artist’s studio, to a series of hanging chastity belts wrought from steel and PVC that reference feminism, childbirth, medieval locks and the French architect Hector Guimard. Her work is minutely researched, and gorgeously distilled. The Hepworth Wakefield is currently hosting Hamilton’s brilliant reimagining of the collection at Kettle’s Yard, complete with her own and other artists’ work, including a desk overflowing with bright red globular forms.