As PHOTOFAIRS prepares to open in San Francisco this weekend, we investigate the storied collection of innovative works showing within it

The photograph: an image of fact, an image of fiction. Almost two centuries on from when the first was created, this form of imagery still has the power to entertain, to educate, to shock and inspire. It’s little wonder that photography fairs continue to draw huge crowds.

Following the third edition of PHOTOFAIRS in Shanghai last year, the fine art photography show has moved west, and this weekend it launches in San Francisco. Made up of highly curated handpicked pieces from around the globe, its aim is to focus on the contemporary; on new and adventurous ways of image-making.

Included within this year’s edition of the fair is a separate platform: Insights. Co-curated by Alexander Montague-Sparey and Allie Haeusslein, this mini exhibition has New Approaches to Photography Since 2000 as its core, and includes many single-edition works from international artists (curated by Montague-Sparey) and West Coast photographers (selected by Haeusslein). “I think San Francisco has [wanted] something like this for a long time,” says Montague-Sparey of the fair, on the eve of its opening. “I’m really excited that it’s finally happening.” Here, we explore four single-edition photographs appearing in the show; extraordinary pieces demonstrating excellence in both process and imagination.

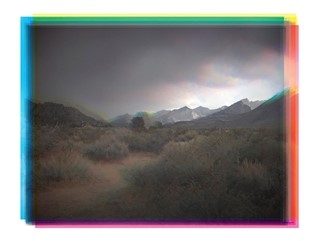

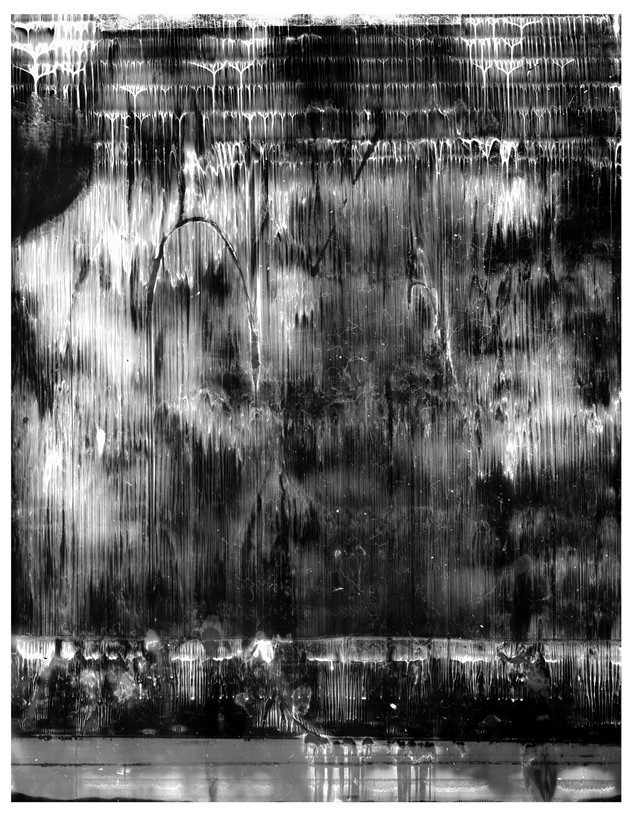

Ester Vonplon, Untitled, 2016

It was at a market in 2003 that Ester Vonplon first bought a camera. She later enrolled in Berlin’s Fotografie am Schiffbauerdamm, graduating in 2007, and soon after, started capturing the great outdoors of Europe – from the Balkans to her home country of Switzerland. To this day, nature continues to influence her work.

Untitled, 2016 originates from the Arctic: “Last summer I got the chance to sail the Arctic Circle by a residency programme,” Vonplon explains. “I tried to capture [its] places and structures with an old 4x5 inch camera on Polaroid film. I [was] searching for abandoned places and the silence one can find in nature. To be out there where no society exists. It’s something that keeps me interested.”

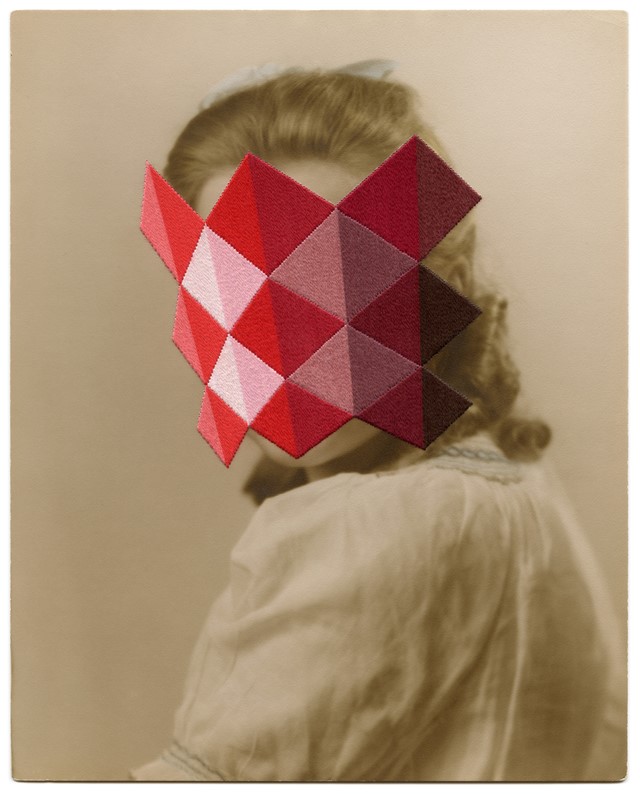

Julie Cockburn, Troublemaker, 2015

British artist Julie Cockburn trained in sculpture, and it’s the sculptor’s expertise that she brings to photography. Sifting through markets and car boot sales, she sources vintage studio portraits and landscapes dating from between the 1940s and 1970s, onto which she embroiders patterns and shapes to create three-dimensional pieces.

Troublemaker depicts a portrait of a woman masked by a stitched graphic grid. “This portrait is part of a series of works I have called The Harlequins which explore the visual play of two and three dimensions,” she says. “These photographs are both image and object, and my stitched interventions go some way to emphasise this both physically and visually.

“Through this process I am also considering the attitude I can give to an abstract form, and how one is compelled to recognise human expression or character in abstract patterns,” she continues. “Here, the colour and shape of my addition gave rise to the title of the piece.”

Anja Niemi, The Receptionist, 2013

Norwegian photographer Anja Niemi is, as Alexander Montague-Sparey explains, “a great example of a young female artist playing with notions of self-portraiture and self-identity.” She choreographs, stars in and shoots her own images, all of which tell captivating narratives. The Receptionist, for example, was shot in The SAS House, a structure built for the Scandinavian Airlines System in Copenhagen, 1960. “The 20-storey hotel was designed in its entirety by the Danish architect Arne Jacobsen,” Anja says. “The hotel has since been remodelled, but one room has been preserved and remains identical to Jacobsen’s original commission. Sleeping in room 606 felt like spending a night in another decade. The room has the industrial feel of an airport lounge combined with domesticality, and was perfect for my character The Receptionist.”

She explains the resulting image merges “darkness with humour. [It] hints to the disparity between who we are and how we want to be perceived.” The SAS building, it is said, looks like a punch card when its windows are open; “I imagine that’s all my character can think about – punching out at the end of the day!” she quips.

Sebastiaan Bremer, Schoener Goetterfunken II B, Daughter of Elysium (Tochter Aus Elysium), 2010

Dutch artist Sebastiaan Bremer first started out recreating his own photographs with paint. In 1998, he attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, where he trialled his now [signature] style of drawing on photographs. Part of a wider series, this piece originates from a box of negatives Sebastiaan discovered featuring images of his parents and siblings on holiday in the Alps in 1973. (He had been too young to go.) “It is hard to make profound remarks about happiness for some reason,” he says, reflecting on his practice. “Perhaps it’s related to what is said about how hard it is to make a good comedy film; it’s easier to faithfully depict drama. For me it is, anyway.”

This series was born of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, he continues. “I set to work with the music blasting – to my ear it sounded heavenly and funky at the same time – and over a three-year period I made a series of works with the overall title Schoener Goettefunken after a line in Ode to Joy that translates as ‘beautiful spark of the gods.’ One by one I amplified the photographs with coloured marks of varying degrees of opacity, enlarging the scene and making the people in the pictures seem to interact, to be almost aware of the marks I added. I wanted them to realise the blissful perfection of the world they inhabited. I wanted them to recognise the joy in that time and that place, surrounded by sparks of the gods.”