We speak to Sara Davidmann, who altered long-hidden photographs to breathe new life into her late uncle’s secret identity, as a new exhibition of her poignant work opens

As an artist making work primarily focused on queer and trans identities, discovering that her late uncle was trans was a fascinating and poignant revelation for Sara Davidmann. She’d always felt an affinity with the trans community that she’d befriended in both a personal and artistic sense, but learning of her uncle Ken’s past through a dusty yet comprehensive archive of photographs, letters, and notes detailing his 1950s research into what it meant to be transgender, shone a whole new light on her family, her identity, and the work she makes. “My mum’s younger sister Hazel married Ken in 1954, and by 1958 he’d realised he wasn’t able to bury his transgenderism any more,” says Davidmann. “That’s what he thought when he married, that he could put it to one side.”

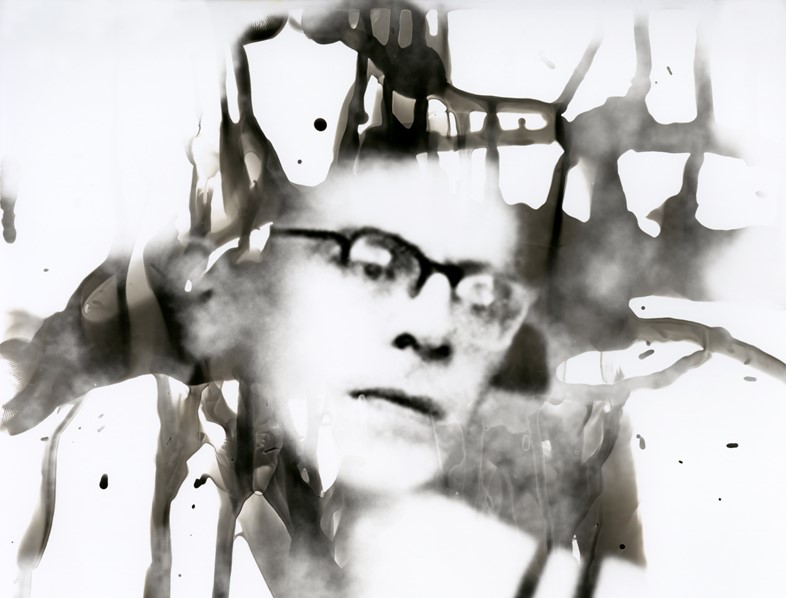

While Ken (who we’ll now refer to as K) was alive, he kept his identity hidden away to all but his loving wife Hazel; but through his letters and the archive photographs of the couple, Davidmann had the chance to rewrite these histories into one where K was free to be herself, to be a woman, and to escape the societal shackles of the time. To do this, Davidmann created her own negatives and worked into them using chemical processes, digital means and hand-colouring, with new images telling of the truths that couldn’t have been revealed all those decades ago. “People assume that if it’s a negative it has to be something that was there, seen, present in the world. Making these sorts of fictional photographs is rewriting something, in a way,” says Davidmann. The works are to go on show in a new exhibition that not only delineates K’s life and family, but also reveals how little we hear about trans people as part of a family. “The media has shown trans people in isolation causing them to be viewed as an ‘other’; but they don’t live like that – they’re parts of families with partners and children, they’re a part of society and have a very social life.”

On discovering the archive…

“My mother first told me my uncle, the person I’d known as Ken, was transgender when I was working on my photography PHD in 2005, but it was only in 2011 that my brother, sister and myself found an archive mum had put together about different aspects of my uncle’s transgenderism. When Hazel died in 2003, my mother went up and found amongst her things a collection of letters Ken wrote to her throughout their lives. They’re love letters really; some are to do with what he wants to happen if he dies before her, and they want to be buried side by side. He died in 1979 and she in 2003, but they were still buried together. The collection was marked to be ‘destroyed’ even though my mother had created it and couldn’t do it herself.”

On what she hopes the work would have meant to K…

“In public Ken was a man, but in the privacy of the home she was a woman. Hazel writes about how Ken felt he was ‘masquerading’ as a man. I think he found it very uncomfortable and difficult, but it was the 1950s and at that time people didn’t know what it meant to be transgender, and if they knew there was almost no support. I hope that she would have been very interested in the work and would have liked it. There are some fictional photographs, and with those in one sense I wanted to give K a freedom she’d never had in her lifetime – the ability to be seen in public as the person she knew she was inside.”

On making the work…

“Some photographs are based on a set that Ken took of Hazel, she’s on her own looking very glamorous and beautiful, so what I wanted to do was also think about how K might have felt taking those photographs. In others I worked on the negatives I made in the darkroom with chemical processes that allowed me to work with painterly mark-making, disrupting them directly in the dark room. It’s a really exciting process: as the person making the images you aren’t entirely in control of the outcome. Part of my desire to work on the images is to have them like vintage photos – they have amazing surface scratches, rips, thumbprints and splodges where mould has affected the print. It’s like those surfaces have become part of the image itself.”

On the parallels between the archive and her own work…

“When my mother told me about my uncle being trans in 2005 it was because of all my work with trans and queer people. I think for a long time she’d been wondering if I’d known and if there was a connection, but I didn’t think about creating artwork based on it until I came across the archive. I was so moved by these letters – if I hadn’t been involved in photography and recording oral histories about transgenderism, and gotten to know transgender people, then it’s possible it might’ve been destroyed. That’s what’s amazing – it has survived. There are very few trans family histories that have. It was significant as a queer artist to know this thing existed.”

On why the show is important now…

“Through art and photography you can reach people in a way that sometimes you can’t by other means – it’s very direct, the way visual images connect with people. Things have changed so much in the last five years or so and people’s understanding of trans issues has changed so much, but when you talk to trans people there are still so many things that need to be addressed. I think art always contributes in some way, even if we’re not aware of it.”

Ken. To be destroyed runs from February 17 – March 26, 2017, at London College of Communication.