We celebrate the Gluck, a rebellious painter who rejected commercialisation and gender norms, as London welcomes a major retrospective of her work

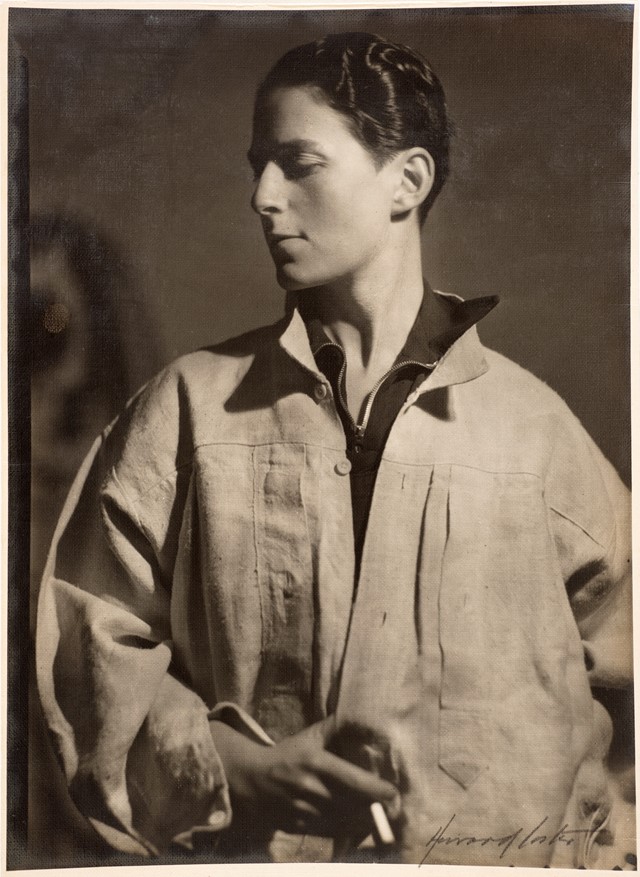

Who? Born in 1895 to a wealthy Jewish family in England, by the age of 23 Hannah Gluckstein had already re-branded herself; shedding her first name she took to signing the back of her paintings and prints with strict instructions: “Please return in good conditions to Gluck, no prefix, suffix, or quotes.” To the dismay of her father Joseph Gluckstein, the co-founder of the catering empire J Lyons & Co, she cropped her hair and took up wearing men’s clothes, as well as smoking a pipe. “I am flourishing in a new garb,” she wrote to her brother in 1918, declaring it “intensely exciting.” Her mother, the American Opera singer Frances Halle, prayed the dressing up was merely a “kink in the brain”, her open lesbianism a “silly mania”, both phases that would soon pass. Yet Gluck’s determined sense of self saw her early career bolstered with media attention; posing for magazines such as Tatler in her signature trousers and tie she became the “young woman who affects pipes and plus fours, and scorns prefixes”, dubbed “ultra-modern” by one newspaper, and the subject of a “guess the gender game” by another. “I just don’t like women’s clothes,” she declared, to her parents’ dismay. “I don’t object to them on other women... but for myself, I won’t have them... I’ve experienced the freedom of men’s attire, and now it would be impossible for me to live in skirts.”

Despite an ardent policing of her appearance, Gluck had many names. Her family called her Hig; to others she was Darling Tim, Peter, a Young English girl, ‘Rabbitskinsnootchbunsnoo’, and to Edith Shackleton Healf, the journalist with whom she lived for many years, she was even ‘Dearest Grub’. In spite of this freedom, ‘Gluck’ became a signature name that she defended ruthlessly in the public sphere, chastising clerks who accidentally added ‘Miss’. She even filed to sue a publisher who dared to release a minor novel with a character called Glück, criticising it as blatant infringement. Yet in many ways, Gluck’s constructed identity was beside the point; what mattered was her work. In changing her name, Gluck was able to reduce herself to a powerful symbol, for minimising her identity had a large part to play in a controlled curation of her presence within the art world.

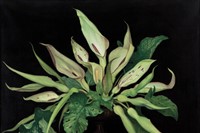

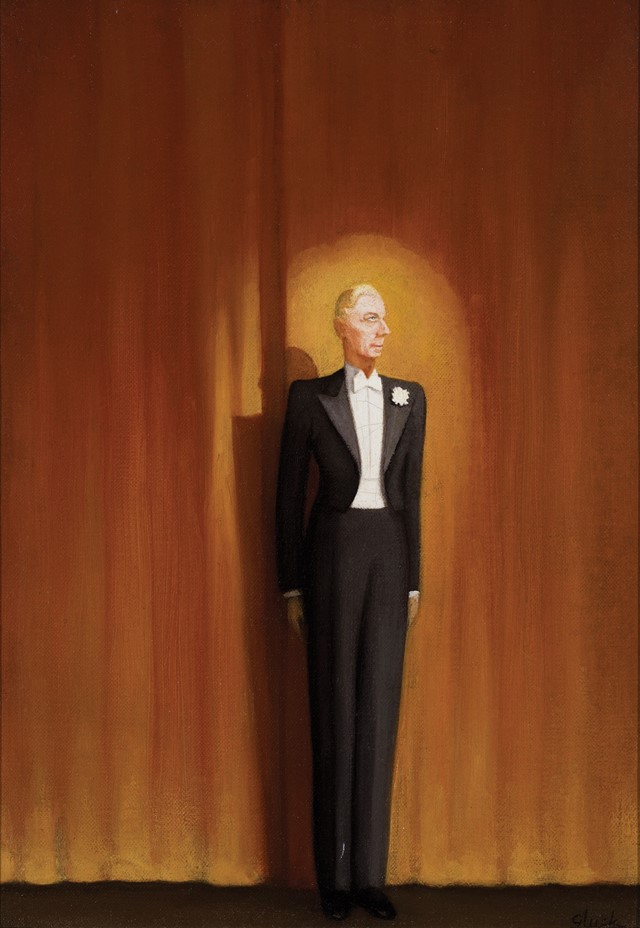

What? “I made a vow that I would never prostitute my work and I never have... Never, never have I attempted to earn my bread at the cost of my work.” Gluck didn’t need to paint. Born into a rich family, she was lucky enough to do so only when she wanted to, and this luxury allowed her to tackle subjects that more commercially driven artists ignored. Her society portraits of women in particular made her stand out from the crowd: a world away from the reclining nudes that peppered the walls of the National Gallery, she saw her contemporary women for what they were, human creatures as complex and malleable as men in their personalities and their attire. Gluck’s women wore belts, ornate hats, their nails painted, lips pouted. Working closely with the society florist Constance Spry, who also happened to be one of her lovers, she entered the world of socialites, including Baroness Molly Mount Temple, the actress Terrie Gerrard, costume designer Margaret Watts, and later Katharine Hepburn – many of whom served as subjects in her work.

Gluck was also never one to shy away from a challenge. When at a party in 1927 a friend declared it impossible to paint a black face against a black background, Gluck instantly put out an advert for a black model in order to disprove the claim, and named the resulting portrait Spiritual. Painting for Gluck did not end at the setting aside of paints and brushes, either – the larger conceptual importance of how a work integrated with its surroundings preoccupied her constantly. As well as depicting ornate interiors and floral decorations, she loved to consider how works would sit within spaces. She even designed, and in 1932 patented, a frame, using three symmetrically stepped panels to assist the integration of images into their surroundings. Gluck exhibited with her signature frames at The Fine Art Society in 1926, 1932 and 1937, and it was here she returned to hold her final solo show in 1973. With such a long history with the artist it only seems fitting that the same gallery be the one to present a major exhibition of the artist’s work now, in 2017.

Why? This impressive retrospective of Gluck’s work will include many of the artist’s best-known paintings, including Medallion (1937), or as Gluck referred to it YouWe, made famous when it was used as the cover of a Virago Press edition of The Well of Loneliness, the controversial novel about lesbian love by Radclyffe Hall. The dual portrait depicts the artist’s lover, the married American socialite Nesta Obermer, almost as a blonde shadow to Gluck’s own sombre self portrait. The two faces are held cheek-to-cheek, so close they could almost be one and the same. In her biography of Gluck, Diana Souhami recalls the night at the opera in 1936 that inspired the painting when the two “sat in the third row” and Gluck “felt the intensity of the music fused them into one person and matched their love.”

A pioneer in both her life, love, and art, Gluck remains a crucial figure in the development of societal attitudes towards androgyny and gender. Largely overlooked because of her self-imposed 20-year hiatus from painting, this substantial showcase will give much needed space to a singular artist who remained a truly creative individual throughout her life.

Gluck runs from February 6 – 28, 2017, at The Fine Art Society, London.