On the 70th anniversary of her death, we spotlight the oft-overlooked female artist whose themes of female empowerment and mastery of form and colour still resonate today

Who? At the age of 21, English artist Winifred Knights was considered one of the most promising painters of her generation. The year was 1920 and she had just graduated from the Slade School of Art and become the first British woman ever to win the highly prestigious Rome Scholarship with her masterful painting The Deluge – a striking metaphor for the horrors of the First World War, which now hangs in the Tate. But when she died from a brain tumour just 27 years later, Knights was banished to the realms of forgotten genius; no obituary appeared for her, and in the extensive Dictionary of National Biography she is listed only as the first wife of artist Sir Thomas Monnington.

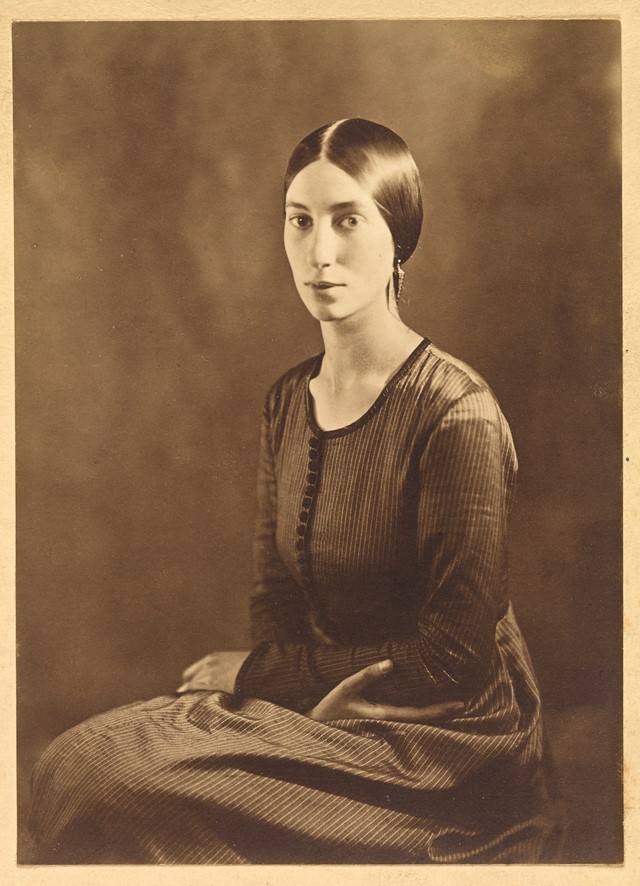

Knights was born in Streatham, London, in 1899 to liberal, middle-class parents who were deeply encouraging of their daughter’s talents as a painter and draughtswoman. She enrolled at the Slade in 1915, where she quickly flourished. In 1917, however, she suffered a bout of anxiety brought on by the presence of ominous zeppelins over Streatham and retreated to her cousins’ farm in Worcestershire where she cultivated the love of nature and simple, outdoor living that would become so distinct within her work. This was further propagated by her beloved Aunt Millicent, a vocal women’s rights campaigner, whose views also influenced Knights’ ongoing exploration of the conflict between female self-empowerment and subjugation through art. From this point onwards Knights styled herself after Millicent in loose bohemian dress, crafted from hand-spun and woven cloth, and wore her dark, centre-parted hair pulled back away from her striking face in a manner reminiscent of a Modigliani muse. She returned to the Slade in 1918 much strengthened to complete her studies, before heading off to Rome in October of 1920.

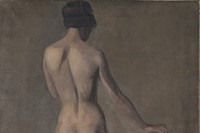

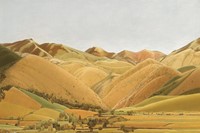

What? The purpose of the scholarship she undertook there was for artists to hone their decorative painting skills, learning the art of large-scale wall decoration from the frescoes of the quattrocento masters, whom Knights revered. The artist’s painstakingly precise eye for detail and astonishing understanding of colour, form and composition lent themselves perfectly to the task, as evidenced in the masterpiece of her Rome period, The Marriage at Cana (1923) and accompanying preparatory sketches – the pale pink watermelons are particularly sumptuous. As with the majority of her work, the painting sees Knights’ borrowing from the naturalistic style of Renaissance artists such as Piero della Francesca, but, imbuing the work with a distinct sense of modernity, as well as including autobiographical elements (three self-portraits, as well as portraits of her then-fiance Arnold Mason and soon-to-be husband Thomas Monnington, are among the banquet’s seated guests). Indeed, Jesus’ transformation of bread into wine, obscured though it is by a figure in the painting, may well be a metaphor for the changes afoot in Knights’ personal life. As Sacha Llewellyn, curator of The Dulwich Picture Gallery’s recent Knights retrospective notes in its accompanying catalogue, “Knights consistently rewrote and reinterpreted fairy tale and legend, biblical narrative and pagan mythology to create visual distillations of her own lived experiences.” Edge of Abruzzi (1924-30), another beautiful work in washed-out pastel tones, begun just after her return from Rome in 1924, depicts a trip she took with Monnington to Abruzzo and shows the pair floating on a lake surrounded by rolling hills – Knights’ idea of rural bliss.

Why? Knights continued to enjoy a brief period of success upon her return to Britain, securing a number of notable commissions, including the breathtaking Santissima Trinita (1924-30), a celebration of the peasant women Knights had encountered during summers spent in the Italian countryside and a musing on female recuperation. But a combination of factors including an innate sense of perfectionism, cultivated by her pernickety Slade tutor Henry Tonks, which made it difficult for her to finish works; a number of commission snubs; the devastating birth of a stillborn boy and an ongoing sense of anxiety even after the birth of a healthy son in 1934, eventually gave way to Knights abandoning her trade altogether. In 1946, her marriage fell apart and the following year she passed away, this week marking the 70th anniversary of her death. Happily, thanks in no small part to Llewellyn’s exhibition and book, this milestone is heralded by a resurgence of interest in the outstandingly talented artist’s work, and, to quote the book’s foreword, her long overdue “establishment as one of the most original artists of the first half of the 20th century”.

Winifred Knights by Sacha Llewellyn is available now, published by Lund Humphries.