Re-discover Vanessa Bell, the colourful painter and sister to Virginia Woolf whose life and work played a pivotal role in Bloomsbury and beyond

Who? “Nessa has all that I should like to have,” Virginia Woolf wrote in 1908. Nessa, as she was known to her friends and family, was Vanessa Bell, Woolf’s elder sister, a painter, designer, wife, mother, and lover. In Woolf’s eyes she was “the Saint,” her character akin to “a bowl of golden water which brims but never overflows”. At the age of 18, after the death of their mother, Bell was charged with the duties of running the household for her father and siblings, but in spite of this early responsibility she still managed to escape to secret drawing classes. Her passion quickly developed into a place at the Royal Academy Schools, where she was taught by John Singer Sargent. It was here that Sargent criticised Bell’s early work as being too grey – a message she clearly took to heart, as she later became one of the finest colourists of her generation.

She was a pivotal figure in the Bloomsbury group, which was famous for “living in squares and loving in circles”. After the death of her brother Thoby, Vanessa married his good friend the art critic Clive Bell, a marriage that would prove to be one of the signature centres of the complex collection of creatives. Both took lovers freely, with Vanessa eventually falling heavily for the painter Duncan Grant, whom she lived with in their ornately decorated Sussex farmhouse, Charleston, which would itself become a hub of Bloomsbury life.

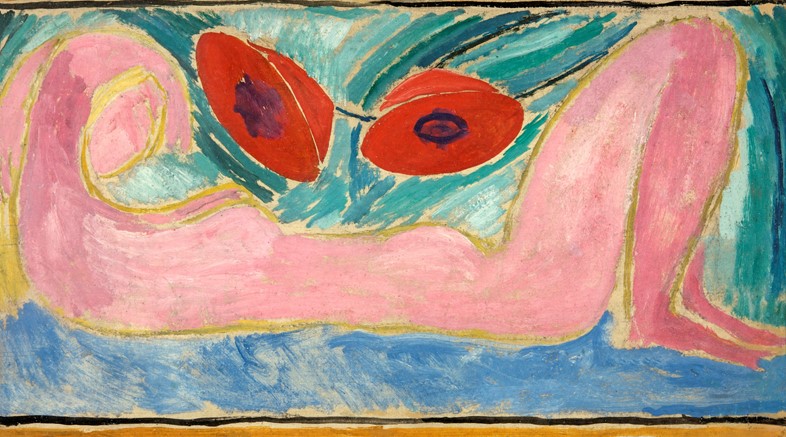

What? “Painting and writing have much to tell each other,” Woolf observed in 1934, and the “silent kingdom” of paint that she so admired was certainly the dominion of her sister. For Woolf, Bell was a poet in colour, her pictures “built up of flying phrases”, “flying off the canvas in rapture” and yet simultaneously “firm as marble, ravishing as a rainbow”, “sunlight crystallised, of diamond durability” and “flashing brilliance”, to quote just a few tributes.

Walking into the London Grafton Galleries in 1910 (it was filled at the time with works by the then virtually unknown Cézanne and Van Gogh at the Post-Impressionist exhibition, organised by the art critic Roger Fry), Bell saw a path for herself. The exhibition overwhelmed her, but also served as a dramatic validation of her work. In the second exhibition, which ran in 1912, Bell would appear alongside the likes of Picasso, Matisse, and Gaugin.

Her extraordinary output of work has long been neglected, and now, finally, The Dulwich Picture Gallery has provided Bell a space apart from her Bloomsbury identity in the first major retrospective of her work. “I think she might have been better off, even better known, if she hadn’t been part of the [Bloomsbury] group,” says co-curator, Sarah Milroy. Bell’s affair with Fry, which began in 1911, certainly made it easy for many to dismiss her work, in spite of the fact that she went on to exhibit internationally.

In 1913, Bell founded The Omega Workshop alongside Fry and Duncan Grant, an artistic co-operative that ran until 1919. It was here that she continued to expand her work beyond the canvas, from representative figurative studies in oils to bold abstract works and angular prints. She worked across different media, even launching a dressmaking department with the intention of making “dresses that would use the fashions but not be like dressmakers’ dresses”, and created colourful, and at times controversial, costumes for the likes of Lady Ottoline Morrell, Iris Tree, and Marjorie Strachey. She also contributed designs for printed linens, Allan Walton fabrics, as well as creating her own bold floral geometric pattern for a collection of Foley China that was introduced at Harrods in 1934.

One of the most exciting aspects of the Dulwich exhibition is its inclusive attitude towards Bell’s artistic output, incorporating all the dimensions of her creative canon, from textiles and furnishings to the famous book jacket designs she produced for Woolf at The Hogarth Press. “It’s entirely out of my head” she told Fry, “[I] like to paint out of my head”, and described herself as “certainly an Impressionist”. Ian Dejardin, co-curator and gallery director, clearly agrees: he lauds the bravery of “the sheer brutality of her brushstrokes – as if hacking at the canvas with the brush”, her “vibrant embrace of colour” and “bold rejection of traditional notions of the beautiful”. For Bell the paintbrush was, in her own words, “the one dependable thing in a world of strife, ruin, chaos”. A tool that enabled her to escape the chaos of the world around her: “When I work I think of nothing else”.

Why? This exhibition will be the first major retrospective of Vanessa Bell’s work. Finally freed from the crowd of her contemporaries and the dramas of her personal life, the gallery gives precedence to her oeuvre above all else, highlighting for the first time her significance as an artist in her own right. A concurrent exhibition will house her photography, another under-explored facet of her artistic output. After all, it is often forgotten that Bell’s great-aunt was the pioneering Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, for whom her mother often posed.

These exciting snapshots into Bell’s life find an unlikely admirer and ally in the iconic Patti Smith, who has created a photographic reply to Bell’s vivid depictions of Bloomsbury life. Smith’s haunting portraits of the rooms and objects that Bell and her Bloomsbury friends left behind evoke the dramatic void of time where, in Smith’s words, “everything has significance”, and contrast movingly with the crowded liveness of Bell’s life where art was part of the everyday. Not only are we shown the beating heart of Bloomsbury, but we are also shown the dramatic echoes it left behind. To paraphrase Bell’s words, art is the only lasting thing.

Vanessa Bell 1879-1961 runs at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, from February 8 until June 4, 2017.