As Tate's history-making exhibition opens tomorrow, we preview ten of the groundbreaking pieces that feature in the show

Tate Britain’s groundbreaking exhibition Queer British Art 1861-1967 – unimaginable not so very long ago – focusses on art produced in a hundred-year period from the repeal of the old ‘Buggery Act’ in 1861 to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967. This unique and timely exhibition explores how covert love and desire were expressed in a dangerously repressive culture where being ‘queer’ could lead to imprisonment and death. Inspired by the sense of liberation artist Derek Jarman experienced in reclaiming a frightening and derogatory word, ‘queer’ is now – as curator Clare Barlow points out – an inclusive critical frame of reference for ‘fluid identities and experiences’ that fall outside mainstream traditions of gender and sexuality and one that should be celebrated.

For audiences, queer or otherwise, art is about recognition. Consciously or not we strive to recognise in works of art something of our own feelings, experiences and identities. Tate Britain’s new exhibition seeks to redress the invisibility of the queer gallery experience. As Barlow makes clear, there isn’t one totalising ‘take’ on any given picture. The interpretation of art is – and should be – multi-layered. Focusing on art (rather than artists) that both ‘speak to’ and have been ‘claimed’ by the LGBTQI community, the works on show evoke diverse resonances and meanings.

1. The Critics by Henry Scott Tuke (1927)

Slade-trained artist Henry Scott Tuke made his name painting young Cornish men bathing, swimming and sunbathing – images that undoubtedly gave distinctly homoerotic pleasure to his many male patrons. The Critics is one of Tuke’s most successful. Two undressed young men resting on the seashore are seen from behind, completely unaware of their archetypal allure as they joke with a third youth obscured by the water. Sensual in subject matter, tonality and brushstroke, the viewer’s perspective is that of the adoring voyeur reminiscent of E. M. Forster’s novel Maurice.

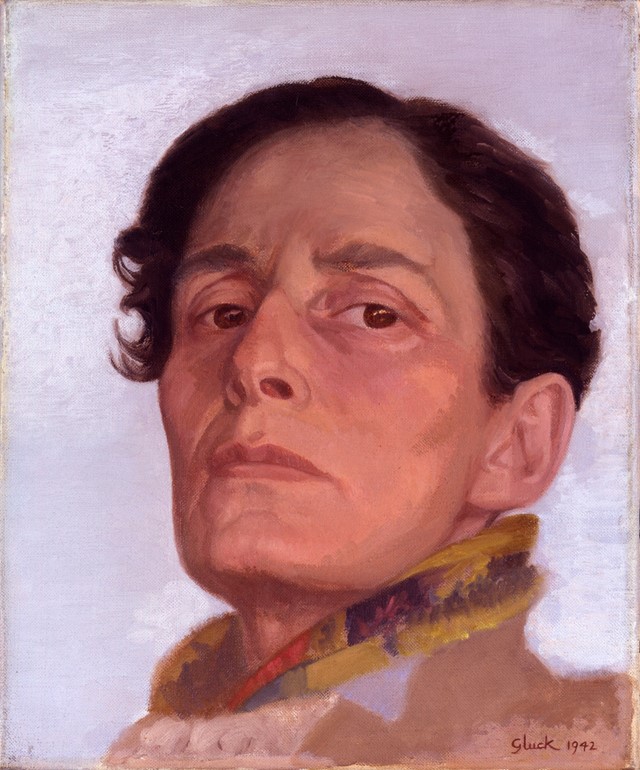

2. Gluck by Hannah Gluckstein (1942)

Born in London to a wealthy Jewish family, the androgynous Gluck, as she liked to be known (“no prefix, suffix or quotes”), led an uncompromising life and career that deliberately avoided easy categorisation. Her compelling wartime self-portrait is like that of an antique bust; her weathered face and defiant expression, set beneath cropped dark hair lilting in the breeze, depicts the self-possession of a modern Prophetess. In youth Gluck was androgynously painted as Peter – A Young English Girl (1923-4) by queer artist Romaine Brooks and would become known for her own haunting portraits of both friends and lovers.

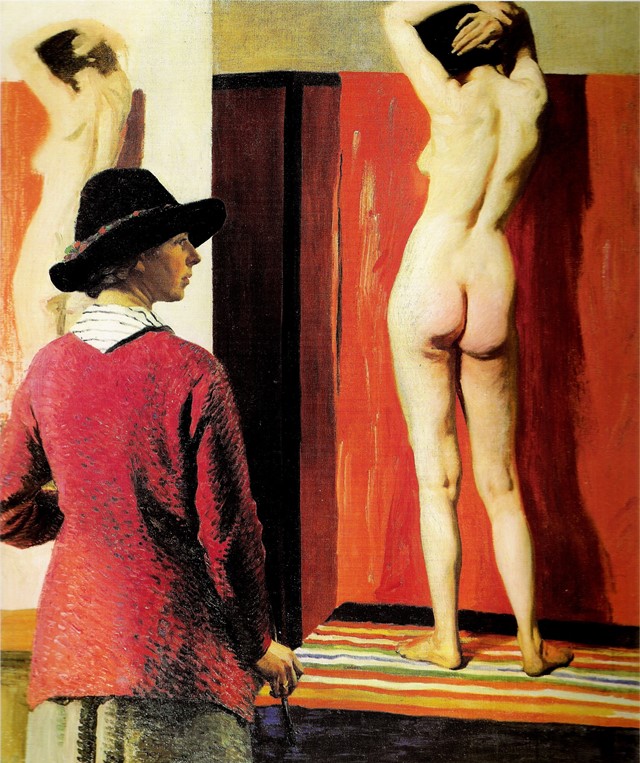

3. Self Portrait and Nude by Laura Knight (1913)

Described by critics in 1913 as “vulgar”, the self portrait of Nottingham-trained artist Laura Knight is confident in a ‘hidden triptych’ that claims the power of her own creative gaze, cast sensuously upon a delicately turned female nude knowingly reproduced on the canvas to their left. With art schools of the period forbidding female students from attending life classes and reminiscent of a character from D. H. Lawrence’s novel Women in Love, Knight improvised at home with her model friend Ella Naper, arresting and reversing centuries of what the feminist critic Laura Mulvey called the ‘male gaze’.

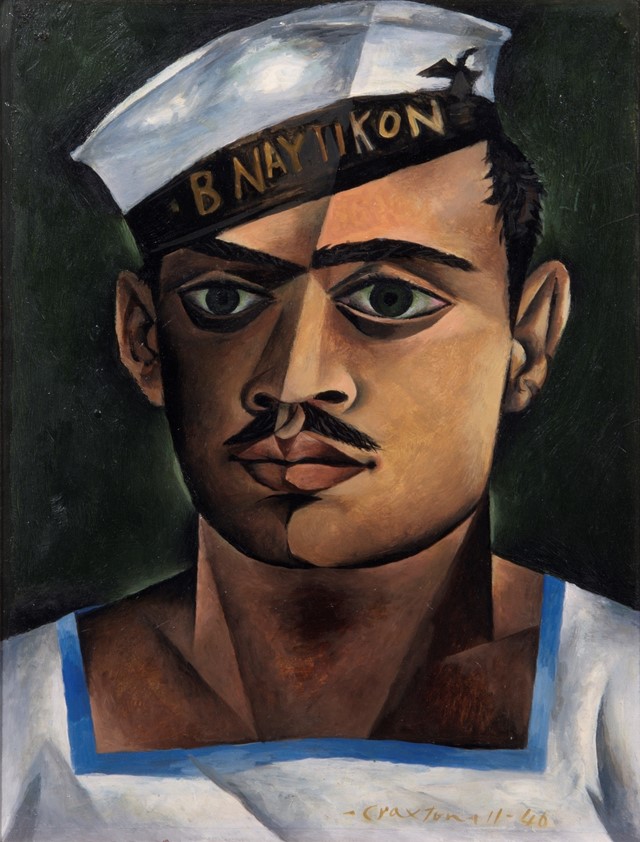

4. Head of a Greek Sailor by John Craxton (1940)

Trained as an artist in London and Paris, John Craxton’s travels in Europe took him to the Greek island of Crete where he became the British Consul. With his Odyssian air of purpose the Greek sailor in Craxton’s portrait evokes the Classical busts of antiquity and the sculptural Neo-Cubist qualities of his face and torso evoke a Renaissance fantasy of hyper-masculinity. It’s as if Picasso mated with Pierre et Gilles. The sailor’s thin moustache is worn heavily as if by a boy newly arrived at manhood and there is an awkward delicacy in the gaze of his eyes; a softness redolent perhaps of a new romance and the knowing awareness of his own attractions.

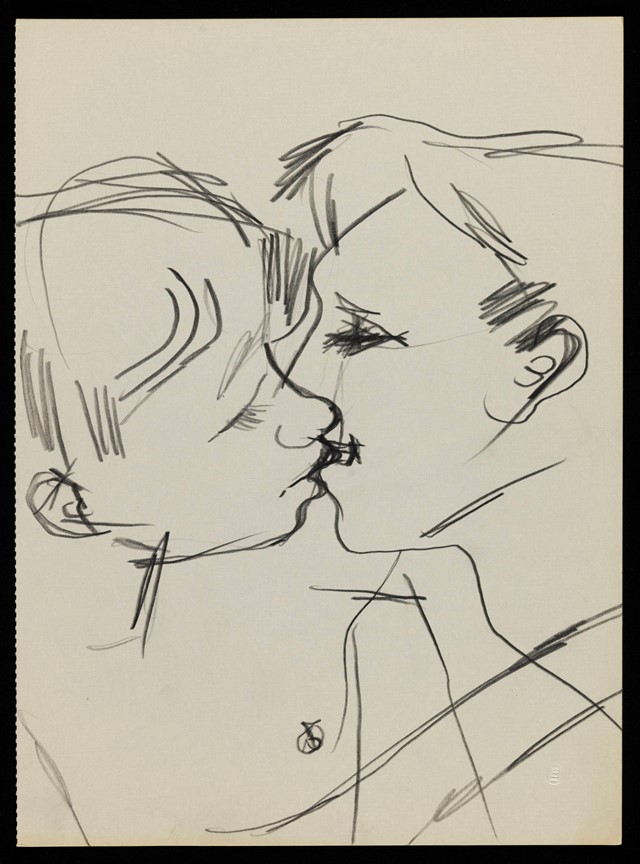

5. Drawing of Two Men Kissing by Keith Vaughan (1958-73)

This simple, accomplished pencil drawing on paper is the most radical piece on display; its delicate, ephemeral quality only enhancing its historic importance. Two men kissing with evident passion is, to say the least, a subject profoundly uncommon in the history of European art. Drawn briskly but with deliberate care, Vaughan’s sketch was conceived during a decade of fear and completed in a decade of liberation. That the sketch is black-edged, however, feels prescient. The AIDS crisis of the 1980s soon returned fear and pain to a new generation of queer men.

6. Paul Roche Reclining by Duncan Grant (c. 1945)

Bloomsbury artist and Charleston-resident Duncan Grant spent much of his life painting the male nude. His monumental Bathing (1911) is on display here too yet his portrait of a reclining Paul Roche best displays the sensuality of Grant’s vibrant Post-Impressionist palette. Apparently sleeping, Roche provocatively arches his back, protrudes his powerful chest and parts his legs wide like the dying Adonis. An invitation to look is explicit, but the touching – at least for Grant – proved rather more difficult (Roche was ordained to the Catholic priesthood two years before the portrait was painted and later married).

7. Tea with Sickert by Ethel Sands (c. 1911-12)

American-born and Paris-trained Ethel Sands enjoyed a prolific career as both an artist and socialite. One of the few female Post-Impressionists working in London before the First World War, she co-founded the London Group of artists and exhibited widely. From an unusual perspective yet with an assured technique, here we glimpse in luscious foreground detail, from above and behind, the awkward plumage of a bohemian lady and absorb from afar the intensity of the artist Walter Sickert’s inscrutable gaze. Sands would later live with her life partner, the artist Anna Hope ‘Nan’ Hudson at the Château d’Auppegard in Northern France (a painting of which is to be included in this exhibition).

8. Figures in a Landscape by Francis Bacon (1956-57)

In life and art, Dublin-born Francis Bacon enjoyed the courting of jeopardy and the elision of sex with violence. In his pictures wrestlers become lovers; lovers become enemies. Rather than courting, lovers claw at each other’s skins in lost desperation. In a decade where homosexuality could prove a prison-sentence, the double bed here becomes a crime scene. As in James’s Baldwin’s contemporaneous novel Giovanni’s Room, criminalised love is painful, and lovers can be brutal. The title invites visions of Arcadian nudes, yet here the hostile outside world becomes internalised, the figures mutilated aliens trapped in a filthy (prison) cell.

9. Going to be a Queen for Tonight by David Hockney (1960)

In the early 1960s Hockney’s abstract Going to be a Queen for Tonight might easily have been mistaken for an angry republican protest. For the queer few however, it playfully located ‘queening’ as a perfomative trope, as easily slipped on as off. There are scrawled words and numbers on the painting’s surface, a vertical and a horizontal repetition of the word Queen and a five-digit number. Initially the faceless numbers provoke anxiety: the Queen is branded as a prison inmate. Yet like Queer, Queen and ‘Queening’ are also archly reclaimed – just as Susan Sontag would soon reclaim Camp in her famous Notes on Camp, the five-digit number a head count of all the subversive Queens out on the town tonight.

10. Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene by Simeon Solomon (1864)

Prominent Pre-Raphaelite Simeon Solomon was born in London to an artistic Jewish family who encouraged his training at the Royal Academy. A pivotal figure of the Victorian avant-garde, Solomon was twice arrested and imprisoned because of his sexuality. The damage these scandals proved to his artistic career forced him into the workhouse for the last 20 years of his life where he understandably succumbed to alcoholism. His Sappho and Erinna, however, is a bold and joyful poetic manifesto of same-sex love and desire symbolised by the commitment of fidelity, the beauty of music and poetry, the blessing of the gods, the haven of a sheltered garden and the potential of a new spring.

Queer British Art 1861-1967 runs from April 5 – October 1, 2017, at Tate Britain, London.