Ayana V. Jackson’s new exhibition spotlights the problematic positioning of blackness in the art world

American artist Ayana V. Jackson was at her studio in Paris when she found out about the recent Dana Schutz-Emmett Till scandal at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, in which Schutz’s painting of the African-American teenager lynched in 1955 was protested against and eventually taken down. “I don’t believe in censorship,” she says, “but that controversy is a good example of a bigger issue: there is more representation of black bodies by white, than black artists. Art is still too focused on the white gaze.” Throughout her career, Jackson has used her photographic practice to shatter stereotypes of black women permeated by that white gaze in photography. “I’m trying to expand the map of blackness and decentralise black america,” she says.

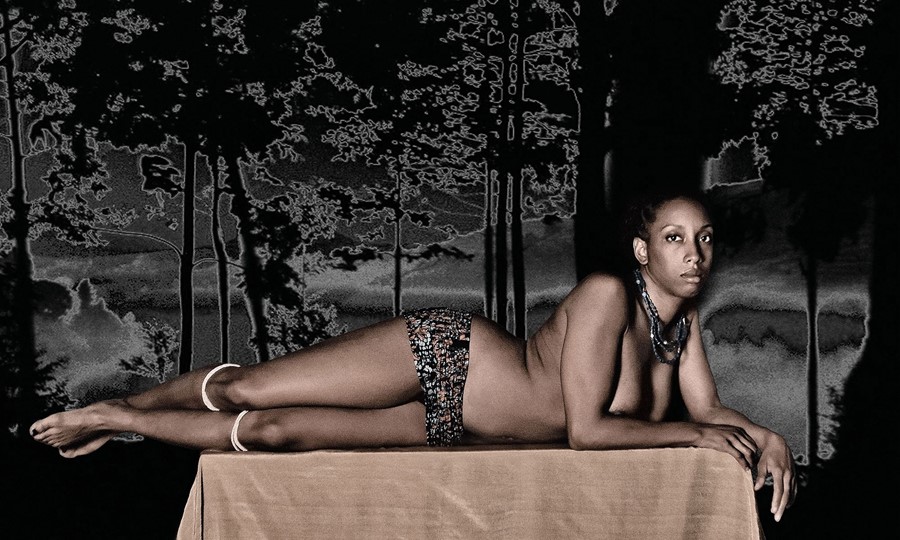

The still image has always been her tool, and she uses it to deal with the complicated relationship between black women and photography, a practice which, in the 19th century, the U.K. and U.S. were fanatical about documenting people of colour with. This obsession often led to images of people in Africa regularly and wrongly sexualised: “they thought the bare breasts of women in tribes were erotic. They weren’t.” In her photography, Jackson plugs the correct narrative back into these wrongly represented bodies.

Jackson draws comparisons between the status of black women in colonial-era photography and contemporary culture. “Her aesthetic reinstatement of the female black body emulates notions of emancipation and free will,” says Mariane Ibrahim, founder and owner of the Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, at which Jackson is showing her exhibition, Dear Sarah: Ayana V. Jackson. Fresh from a trip to Art Paris, we spoke with the artist about activism, debate and the danger of being the only black voice in a room.

On being her own model...

“The history of photography is complicit in racial stereotypes, it has asserted strange and wrong views of black women. I’m interested in colonial black female stereotyping, and how photography has leveraged these tropes. As a student in Berlin, we had been studying the white male gaze, Susan Sontag and so on, and I was photographing people of African descent. One of my classmates said I was falling into the trap of issues of representation – had I been a white male people would have had issues with my work. I defended myself but it nagged at me – so I started to work with my own body, because using yourself is a much less aggressive act, otherwise it would only be my gaze on another woman. There’s a Czech artist, Katharina Sieverding, whose use of her own body has also influenced me to some extent.”

On her upcoming exhibition...

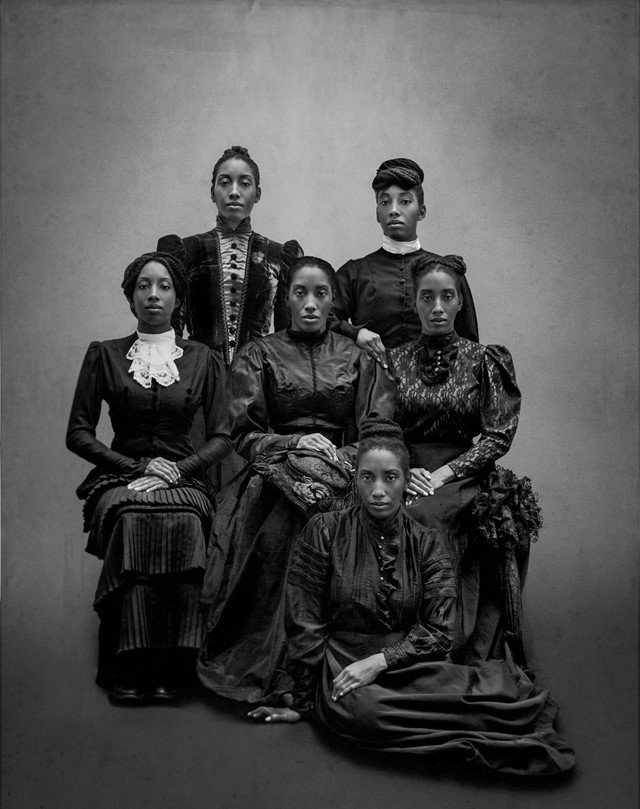

“It’s an homage to Sarah Forbes Bonetta, the Nigerian Yoruba woman who was captured as a slave and then given as a gift to Queen Victoria, who became her godmother. Queen Victoria, like many Victorians, was obsessed with photography, and she photographed Sacha, but everything we know about her is in this inanimate static place. I wanted to give her motion – and I put her in blue, the colour associated with royalty, as she was born royalty.”

On being the only black person in the room...

“In Paris a few years ago, I went to the show of my friend Fred Wilson and he said to me, ‘thank you so much for coming because if you weren’t here, I would be the only black person in the room’. His work being consumed by a wealthy white audience was a bit ironic. I ended up going to the collectors' dinner after, where people who had ignored me during the reception, now seeing me as a guest, were suddenly interested in me – but asking me almost anthropological questions. When you’re the only black person in the room, it can feel like you are part of an anthropological study – dissecting this problem is what much of my work is about.”

On art as activism...

“I’m an activist first, an artist second, it’s visual activism. It’s using photography to fight photography. It still comes back to me wanting to fight to feel right in this black body that I inhabit without being ghettoised. If we can allow our collective humanity to acknowledge race as a fiction then perhaps we can enter into a more egalitarian space. I don’t mind being identifying as a black artist, but I’d like to be just as in conversation with the medium of photography – I get put in more shows about Africa than I do photography.”

Dear Sarah: Ayana V. Jackson runs from April 6 until May 20, 2017 at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Seattle.