Paul Housley’s unsettling portraits and still lifes speak of the blank canvas at the heart of our constructed identities, playfully toying with our notions of what it means to be “real” in a world that still relies heavily on Cartesian notions to

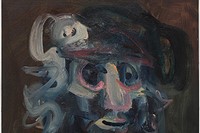

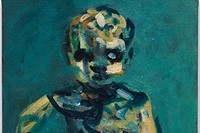

Paul Housley’s unsettling portraits and still lifes speak of the blank canvas at the heart of our constructed identities, playfully toying with our notions of what it means to be “real” in a world that still relies heavily on Cartesian notions to frame the physical environment that we traverse. He breathes strange life into the inanimate objects he works on, while stripping detail and nuance away from his human subjects, inviting us to fill in the blanks – to place ourselves in the frames he has created via the shadowy recognition of archetypal forms. In a sense, Housley shines the magic lantern, in which the image you are most likely to decipher is a mirror image of your own. In anticipation of his forthcoming show at Poppy Sebire, AnOther took some time to find out what makes him tick, and why there is an absurdist aesthetic driving his investigations into the human soul.

“I suppose like a lot of artists I was a quiet and slightly withdrawn child who spent many hours in his own company daydreaming. This has stood me in good stead as a painter, because one of the requirements is the ability to spend long periods on your own in a room making something out of nothing. I suppose I’m saying that my temperament always suited painting. My first real encounter with art would have been through books and album covers. In terms of influence and inspiration, I look at everything – you can learn from bad painting as well as good. I don't think you can go wrong with Velazquez though, he was a magician with paint. I do not particularly seek out the ‘dark’ in my work but, of course, it is there to some degree, usually in the form of slightly humorous melancholy. The objects I choose to paint have what I call a ‘neglected beauty’ – slightly worn and battered by life but always with an air of dignity and a defiance of sorts. I always avoid kitsch, these things ask for no sympathy. What are often referred to as the ‘blank’ or ‘dumb’ elements of my subjects are part of the acknowledgement of the limitations of the medium to fully articulate a totally accurate and meaningful response to life. Ideally, I would like my work to aspire to the condition of music, where meaning and form are as one. To be alive is to be in flux and I have learnt to embrace change. I am constantly looking to surprise myself and looking for breakthroughs, where something is achieved that was not possible to me before. These breakthroughs are a mixture of technical skills and emotional depths that can only be brought about by the many hours spent alone in the studio. While I am in the process of making a painting, the image, surface and even possible meaning can change – and in my case must change – several times over: the final outcome must always be something of a revelation, no matter how small, and that is something that often remains un-noticed by the casual observer. I believe there is something magical about paint that goes far beyond mere illusionist tricks – a great piece of work becomes ‘believable’ and authentic, it has what I call presence and is of itself… beyond the artist. There is no nostalgia in art. Every great piece of artwork exists in the ‘eternal now’ – when you look at a Rembrandt what was true then is still true now… I think the absurdities of life can be read in a man’s face for anyone with eyes to see (this may end up as a title for a painting!). Life is somewhat inherently absurd and it must be acknowledged as such in any meaningful piece of art.”

Text by John-Paul Pryor