Examining our assumptions about artistic identity, a new tome explores the nuances of collaborative relationships

In most media – from film and theatre to music, TV and fashion – creative collaboration is the norm. In the art world, however, prestige tends to cling to the individual. A new tome by by Ellen Mara De Wachter, Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration, seeks to unpick this attitude and, drawing from an inexhaustive pool of examples, highlights the arbitrary differences between single and multiple entity artists. Themes of anonymity, security and identity guide the course of the book, while love – that of friendship, romance or familial relationships – emerges as a driving force for creative works. From symbiotic duos to amorphous collectives, it seems that great work can come from sharing.

1. Guerrilla Girls (above)

Brought together by outrage at the lack of diversity in MoMA’s International Survey of Painting and Sculpture in 1984, this group of anonymous radical feminists conjoined in a bid to protest. Creating propaganda-esque posters that now hang in galleries worldwide – Do Women Have to be Naked to Get into The Met. Museum? (1989) is their most famous – this gang of gorilla-masked artists eschew individual applause in favour of the liberation granted by divorcing your ‘self’ from your work. As one of the group professes: “you wouldn’t believe what comes out of your mouth when you’re wearing a gorilla mask”. Besides the liberation offered by this collaborative approach, their work offers a comment on the art market itself too: “The concept of the individual genius artist is outdated, anyway, kept alive by an art market that needs super expensive art objects made by ‘geniuses’.”

2. Elmgreen & Dragset

Having met in a nightclub in Copenhagen and started a romantic relationship, Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset’s union gradually developed into a collaborative artistic practice. The pair began to create mise en scene installations and the homogeneity of their same sex relationship inspired themes of gay identity and mirroring in their work. Marriage (2004), a pair of matching sinks linked by wildly contorting pipes, exemplified this, as did Boy Scout (2008), an installation of bunk beds with mattresses that face each other. “There are certainly a lot of male artists who have been heavily supported by their female spouses, but it is never even mentioned that they are part of the whole production and planning. Artists who run studios also use their assistants for more than practical stuff, packing, crating and putting screws into works [...] I would say that working together as an ‘artist duo’ is just a formalised collaboration – a working process without lying about your inspirational sources, somehow.”

In 2009, the pair curated both of their national pavilions – Elmgreen is Danish and Dragset Nordic – at the 53rd Venice Biennale. “Our names were shortened in biennials and big group shows because we occupied too much space with our full names,” explains Elmgreen. “And galleries suddenly left out our first names, so we simply became this corporate sounding brand name, ‘Elmgreen and Dragset’. And we thought, ‘Okay. Whatever.’” “The Italians called us Bang & Olufsen for years, the only other Scandinavian collaborators they knew!” Dragset adds.

3. Jane Wilson and Louise Wilson

Studying almost 200 miles apart, sisters Louise and Jane Wilson used their work to challenge the art world institutions from the outset of their careers. Submitting duplications of their joint project (subjecting themselves to hypnosis) for their respective BA shows, the siblings confounded their school syllabuses. “It meant that our tutors had to collaborate,” Jane explains. “They had to talk to each other on the phone because they were assessing what was effectively the same work, and if they’d passed one and failed the other…” As such their submissions challenged the subjectivity of art assessment.

A further confrontation to the academic rulebook, the pair went on to make a joint application for their MA. A credit to its progressive tutorship, Goldsmiths College was one of the only universities to be flexible enough to let this happen. While undertaking the MA course they shared a studio and each contributed on a part-time basis (the sisters took LSD for their graduation show video work) and joined the throngs of YBAs to emerge from the famed university. In 1999, the sisters were nominated for the Turner Prize in an acknowledgement of the Wilsons’ impact on these often staid institutions.

4. Assemble

Assemble began as a small group of architecture students at Cambridge University. Having expanded to an amorphous group of approximately 20 people – “that’s how many are on the lunch rota” – the art-craft-design-building-collective maintains a group anonymity, refusing to publish a list of names or members. They made their name with the creation of The Cineroleum (2010): the reclamation of a disused petrol station on Clerkenwell Road that became an outdoor cinema. The collective went on to win the Turner Prize in 2015 for its project Granby Four Streets, which saw it redevelop an area in Liverpool that had been subject to “managed decline” since the 1990s – a deliberate disinvestment from public services. These projects embody their communal ethos, both outwards and in. Their methods engaging a communal spirit of creativity in order to realise community-engaging projects.

“We were really just having fun and experimenting for ourselves,” Assemble explains. “So to be able to say that you authored something individually would have gone against the way in which the work had come about. I suppose it has got something to do with the hierarchy of the broader architectural world, because we were all indoctrinated to believe that we couldn’t have a voice because we were, at that time, too inexperienced. So there was a clear feeling that we were still students and because of that, we had a freedom to do what we wanted. When we launched the project and people came to see it, it became clear what we were doing had implications within a wider discourse, and that discourse itself had value, and we realised inadvertently that we did have a voice.”

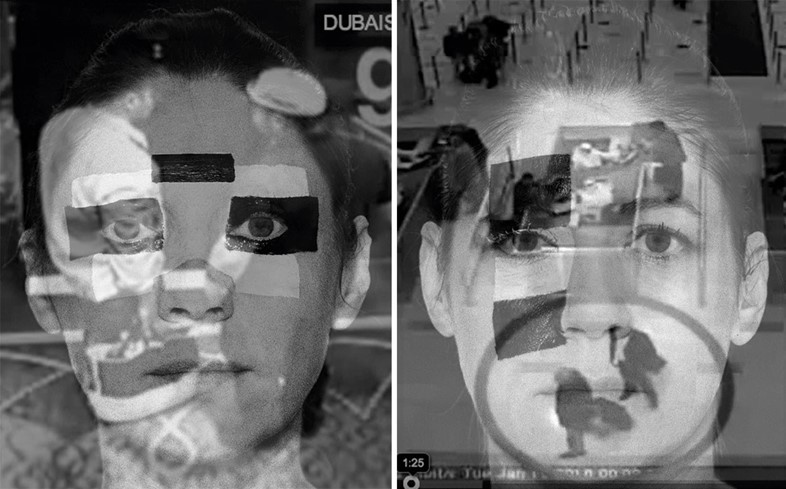

5. Broomberg and Chanarin

Documentary photographers and artists Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin were awarded the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize for their book War Primer 2, described as a “book that physically inhabits the pages of Bertolt Brecht’s remarkable 1955 publication War Primer”. They were awarded the International Center of Photography Infinity Award for their publication, Holy Bible.

The artist duo’s work explores photography as a medium usually associated with a single author since, as Co-Art’s author Ellen Mara de Wachter explains, the mechanics of the modern camera is intended for one person’s eye. To address this notion, they used a medium format camera with a ground glass viewing plate, which enabled them to crowd under a black cloth together to view the subject. “The whole history of photography is premised on the idea of somebody looking with one eye through a lens and with one finger clicking a button,” says Chanarin. “That’s the mythology. So immediately to be two destroys the foundations of the history of photography.”

Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration is out now, published by Phaidon.