From sublime waterfalls to erotic courtesans, we examine the extraordinary work of Hokusai, unveiled in a new London show today

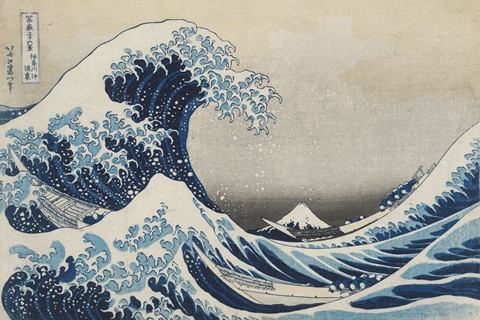

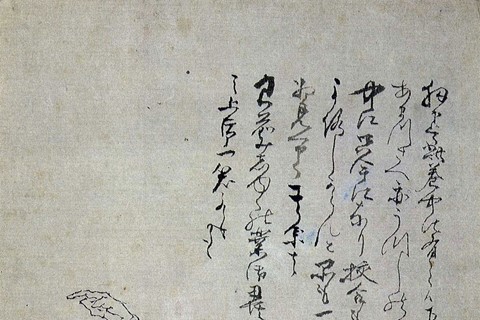

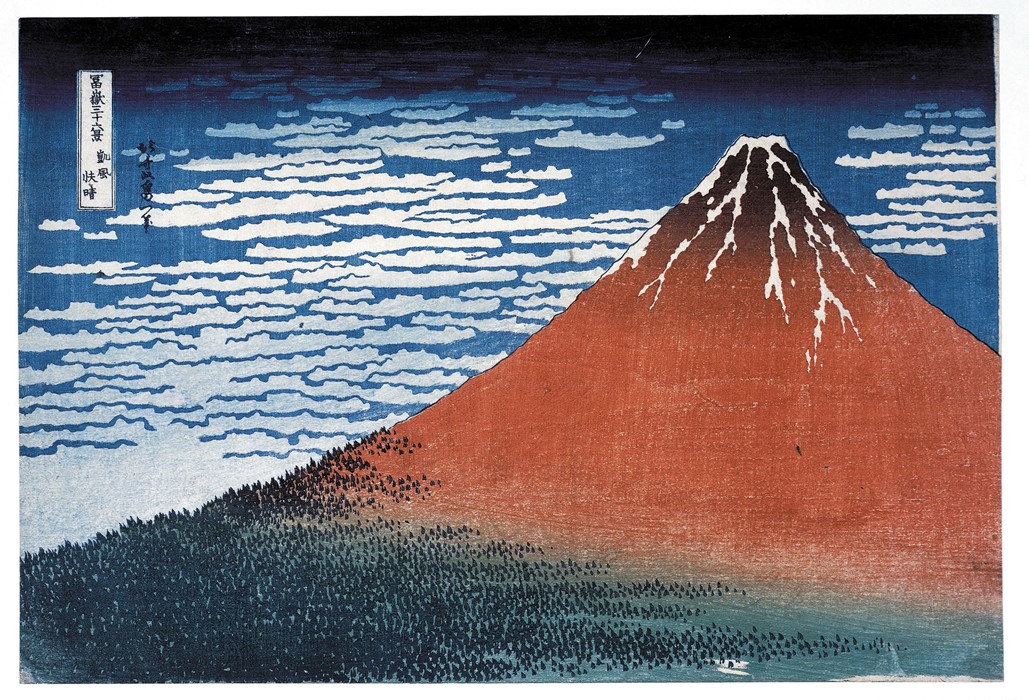

Who? Possibly the greatest Japanese artist known to the world, Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849) authored one of the most iconic images of art history in The Great Wave. Soon after making the series of that woodblock print – Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji – Hokusai, then in his 80s, would humbly announce that his goal was to reach a level of artistic and spiritual perfection by the wise old age of 110. Supposedly only then would, ‘each dot, each line possess a life of its own’. Though he didn’t make it past 90, Hokusai’s prolific oeuvre spanned far and wide: prints of sublime landscapes and mythological creatures; paintings of beautiful women, flora and fauna; sketches of deities and erotic figures; volumes of illustrated novels; and manuals for aspiring craftsmen. In line with a tradition of artists adopting different names to differentiate styles, the painter and draughtsman would use dozens of monikers throughout his career, of which Hokusai, or ‘North Star Studio’, prevailed.

His childhood name, though, was Tokitarō. Born to an artisan family in Edo – a bustling city in the mid-18th century, now Tokyo – Hokusai began painting from the age of six. At 12, his father sent him to work in a library of books made from woodcut blocks, a popular form of entertainment for the well-to-do echelons of Japanese society. After serving as an apprentice to a woodcarver for four years, at 18 Hokusai joined the prestigious studio of Katsukawa Shunshō, a leader of the ukiyo-e genre that centred on Kabuki theatre actors and courtesans of the Yoshiwara pleasure district. Married twice during this time, Hokusai was eventually expelled from Shunshō’s studio for studying at a rival workshop. But this red card was a gateway to develop his own fiercely individual work, which is currently being celebrated in a major exhibition, Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave, at the British Museum until August 13.

What? It might have been the slight but spectacular 15-inch print of a stormy wave enveloping Mt. Fuji that made him his name, but Hokusai was a man of many talents. One overlooked area of Hokusai’s oeuvre were his performances, which would later earn him a place among the kijin, or eccentric artists of the time. 1804 was the year Hokusai first took to the stage, pacing over 350 square metres of paper while painting with a bamboo broom dipped in ink – the result of which was only clear to the crowd once framed to reveal an astounding portrait of Daruma, patriarch of Zen Buddhism. Such acts notably took place when Hokusai was firmly establishing himself as an artist independent of both Shunshō’s studio and the Tawaraya painting school that he subsequently ran.

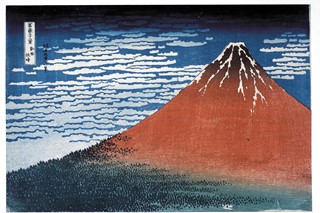

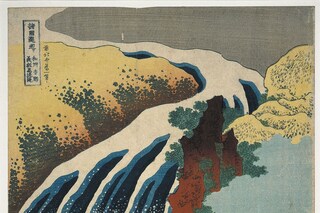

The show at the British Museum, however, begins even later, in the last 30 years of the artist’s life. These years were arguably the most fruitful, commencing with a new name, Iitsu, to commemorate his 60th birthday. In Japanese tradition this milestone year marks a full cycle of signs of the zodiac and the auspicious beginning of a new life. Itsu was the name that stamped his most famous series of landscapes – a genre that saw Hokusai focus on the elemental power of nature and its relationship to the supernatural. He would translate the awe-inspiring beauty of his surroundings into prints such as the Tour of Japanese Waterfalls, while his paintings revealed an extraordinary bestiary of dragons, Chinese lions, phoenixes and eagles, increasingly possessing human expressions and psychological characteristics.

Why? Reproduced on mugs and magnets alike, Hokusai’s art pervades popular culture. It was as trade objects rather than high art that his prints and illustrations first made it to European shores. These objects, among many others by Japanese craftsmen, had a groundbreaking influence on artists from Manet to Van Gogh, kick-starting the Impressionist vogue of ‘Japonisme’. But, while the nation’s philosophy and aesthetics – in particular, its flat perspective, use of blue pigment and thick black outlines – pervaded European art, it was Hokusai who Degas famously hailed as ‘an island, a continent, a whole world in himself’. The show at the British Museum attests to this accolade, but also indicates the ways in which Hokusai took visual cues from Western art. It equally prompts us to take a leaf out of Hokusai’s book – one marked by dogged determination to master every single one of his crafts.

Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave runs until August 13, 2017 at the British Museum.