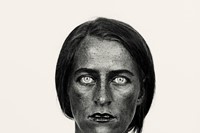

The South African photographer discusses the crisis faced by photography on the occasion of his vast solo show at Germany’s Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

Whether directly or not, you’ve almost definitely seen Pieter Hugo’s work – or at least his ideas. The South African photographer shot to prominence in the mid-2000s, most notably with his 2007 series The Hyena and Other Men. It’s this project that’s been appropriated the most: the jaw-dropping similarities in Beyonce’s video for Girls is the most glaring example, though Hugo also claims that Nick Cave’s Grinderman project used “at least a dozen direct visual copies from my Nollywood series” in the video for Heathen Child.

In the ten years that have passed since The Hyena and Other Men, Hugo has learned a lot; not least about being “pigeonholed” as an African artist (his work is far more international in scope than many would realise, encompassing advertorials and fashion as well as fine art), and about ultimately having to relinquish control of the perception of images you create as an artist.

“I never expected it to blow up the way it did,” says Hugo of Hyena, “and in some ways it was fantastic because it was like a jump start to my career as an artist. But maybe it happened too quickly – it was a bit of a baptism of fire. When I see those portraits again they really do feel like old friends. It feels like another lifetime. But in another way they’ve become so ubiquitous they don’t feel like they’re belong to me – they belong to society.”

Hugo’s work is currently on show in a vast solo show that acts as a retrospective of sorts titled Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, at Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg in Germany. We spoke to him about the relationships between photography and identity, dealing with criticism, and learning on the job.

On how he got where he is….

“I didn’t study anything, I started out as a photojournalist. It’s not that hard to learn how to shoot – the hardest thing is to find a voice. With a good photographer, you immediately know it’s their work.

“My work used to be incredibly confrontational: I wanted to point at things and say to society, “Look, look!” I wanted people to feel uncomfortable and be aware of their hypocrisy. There was an incredible anger there. Then that moved on to something more nuanced and ambiguous and opaque, less sure of itself.

“I’m quite a light person if you meet me but I’m quite heavy in my work, and in the process of making the picture you imbue that with a sense of gravity and urgency.”

On growing up in South Africa in the 90s…

“If one has to be reductive about my practice it’s not about Africa, it’s about outsiderness and the margins and the periphery of society, whether that’s literal or metaphorical. A lot of my work deals with post-revolutionary societies, like the California Wildflower series, or the idea of the colonial experience. The Kin series in South Africa shows those constant tensions between historical narratives and the switches that happen in different cultures.

“Growing up in South Africa in the 90s, and being so aware of the hypocrisy of the white community and the glaringly obvious problems and ironies there, photography gave me an excuse to engage with that, and try to figure out my position. That’s always been a part of what I love about photography, but now I’m much more engaged with the vocabulary of the discipline too.”

On dealing with criticism…

“When I made The Hyena and Other Men I suddenly had to articulate and express my intentions and defend the work, because on one level it was incredibly successful and on another it received a lot of criticism. I wasn’t ready for that: I was young and I came from a journalistic background, then moved into the fine art world and had no formal training.

“But imagine having work that doesn’t get people upset – what’s the relevance of it? It’s been a journey to learn to separate my personal investment in the work and the criticism in it, and finding my way through the morass. One of the things intrinsic to the medium of photography is that it’s inherently voyeuristic, and that’s what gives the medium a lot of energy. But it also creates problems that you have to solve.”

On choosing the exhibition title…

“I wanted something that meant that if we wanted to add to it or develop it later on, we could. I was having lots of conversations with the curator about the crisis that the medium of photography and myself as a practitioner are facing. Photography in particular as a medium is so tied to the baggage that the viewer brings to the image, and that reading is often so different to what my intentions are. The title is a bit like ‘out of the frying pan and into the fire,’ or, ‘I’m screwed whatever.’”

On putting the show together…

“It was only when I started installing the show that I realised the gravity of it: it’s huge, there’s over 250 works in it and I doubt in my life I’ll ever have a show of that physical scale again. I look at the work regularly but I don’t often see the prints as a lot of them are quite large so I don’t have the storage for them.

“It was like a milestone event in your life, like getting married or dying. It was like seeing all my old friends together. Maybe it’s a Protestant guilt thing but I always feel like I’m not doing anything, and spending half my time sitting in a pub, then when you see it you’re reassured you’ve not just been sitting on your hands.”

Pieter Hugo: Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea runs until July 23, 2017 at Kunstmuseum, Wolfsburg.