If you already live in a big city, you’ll likely be all too familiar with the horror of rush hour. Week on week, millions of people around the world spend their mornings and evenings in a breathless metal tube, staring into the middle distance and wishing they were anywhere else. It’s an enforced moment of solitude in the most brutally public of places – a micro-glimpse into another person’s life, even as you ignore them.

German photographer Michael Wolf has made a career out of photographing the more extreme edges of this experience. Shimo-Kitazawa in Tokyo is the most crowded train station in the world, with an average of 3.64 million passengers passing through its bowels every day. On March 25, 2013, the Odakyu subway line which passed though Shimo-Kitazawa went underground. At intervals of 80 seconds, all hours of the day, a new train would pull into the stations, as commuters piled on to grind their way from home to work and back again. From that point until the present day, Wolf would stand on the platform to take portraits of the citizens of Tokyo as they experienced this “subterranean hell”.

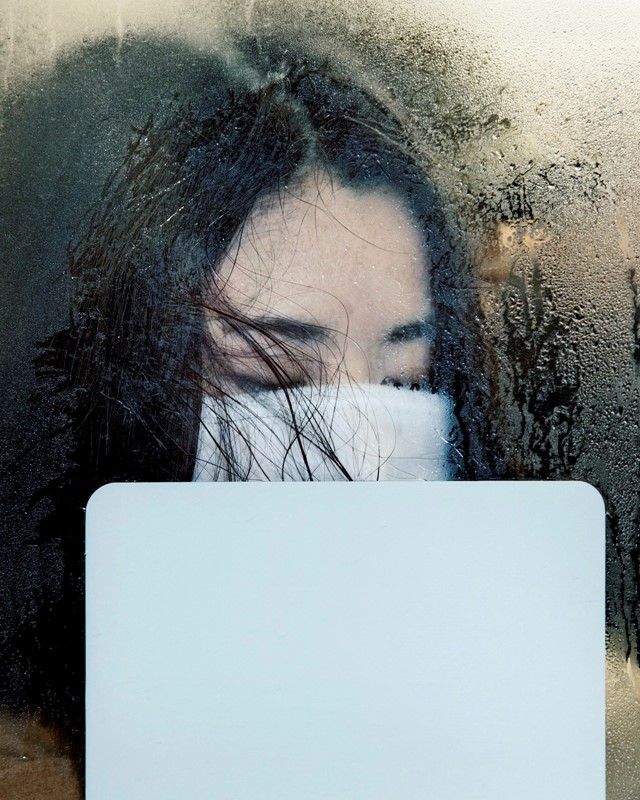

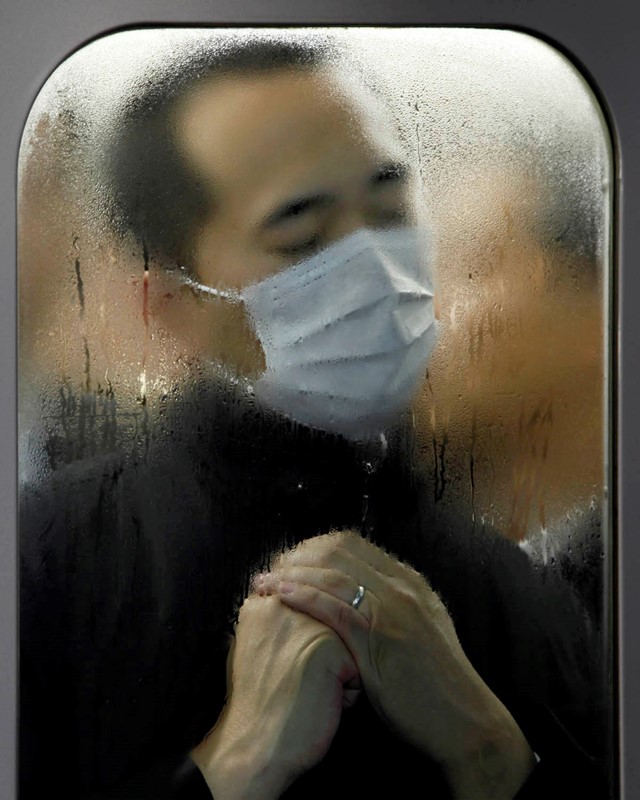

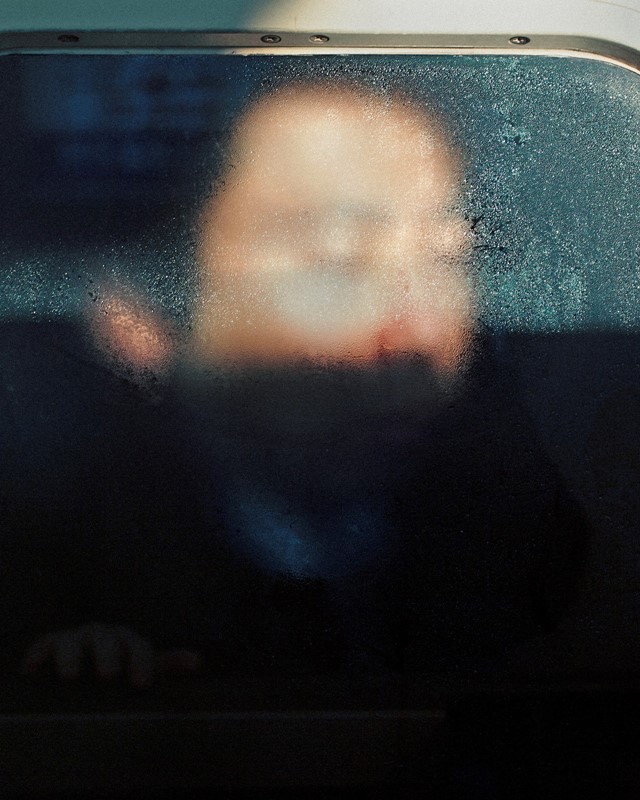

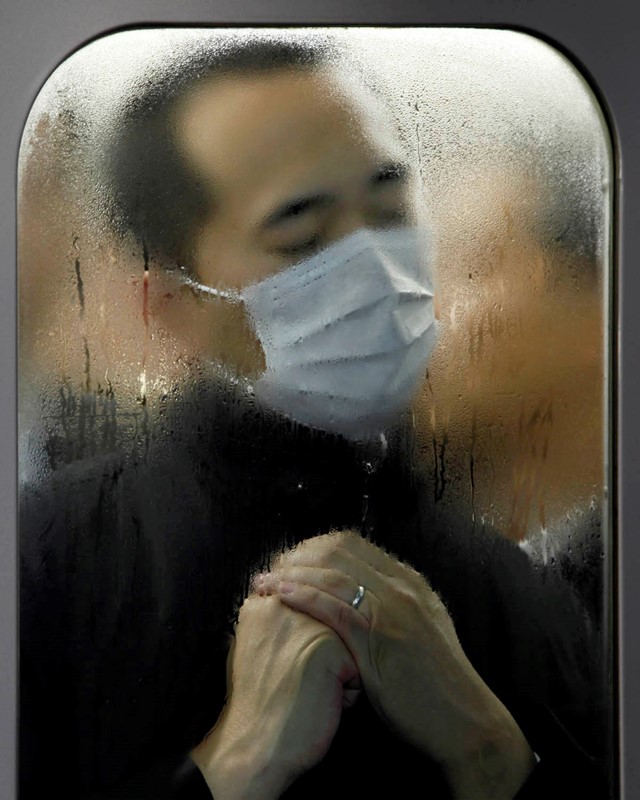

“A train would pull in, and would already be packed to the absolute limit,” Wolf says. “Yet even more people found a way to push on, until they were jammed like sardines in a can.” Wolf would photograph the commuters in the moments before the train pulled out of the station, their faces peering through the windows partly concealed by the collected condensation of a carriage full of breathing people. Sometimes they’re aware of the camera. Oftentimes they seem focused on their own internal worlds.

In his subjects’ faces, Wolf says, we see a vision of “complete vulnerability”. “Day in day out, millions of commuters must endure this torture, as the only affordable housing is hours away outside of the city centre.” In the capture of these contradictory public/private moments, communicated through the smallest gradation of expression and gesture, Wolf has found a way to hint at what might be passing through his subjects’ minds. “He could be mourning the loss of a lover,” he says of one of the many pictures of a man looking impassively, almost inscrutably sad. Referring to a woman, Wolf says: “She could be defending her solitude against the imposition of the chance community.” To a third, another man: “He might realise that he has long since begun to die and is travelling what remains of his life.”

Wolf’s portraits, collected into a series called Tokyo Compression, will be a key component of a retrospective at Rencontres d’Arles, the summer photography festival in the south of France, first founded in 1970 by Lucien Clergue. It is currently showing in Shoreditch’s Flowers Gallery until July 1.

Also on display at Arles is Architecture of Density, the series Wolf worked on when he first moved to Hong Kong in 1991, as a correspondent for the German magazine Stern. He lived in a 22-storey high building, “set in the middle of what seemed to be a forest of high-rises”. Hong Kong is a city of seven million people living in 426 square miles. As he settled into his new home, Wolf recalls the wonder he took in the multitude of other lives, all pressed so seamlessly together. “When it got dark and the lights went on in the tens of thousands of apartments that surrounded me, I would sit at my window and look into the rooms of my neighbours.” That combination of “the anonymous and the intimate” resulted in Wolf’s stunning large-format photographs of Hong Kong’s Blade Runner-esque homes, taken without view of the sky or ground. They’re studies of humanity’s ability to tesselate, even against the odds; of our willingness to live all piled up and pressed against each other. These are, in many way, frightening and foreboding pictures – and rather beautiful too.

Michael Wolf, Tokyo Compression runs until July 1, 2017 at Flowers Gallery, London. Life in Cities runs from July 3 until August 27, 2017 at Arles, Les Rencontres de la Photographie.