Over his 60 years in photographic reportage, Neil Libbert has turned his lens to the good, the bad and the unfair, a new exhibition demonstrates

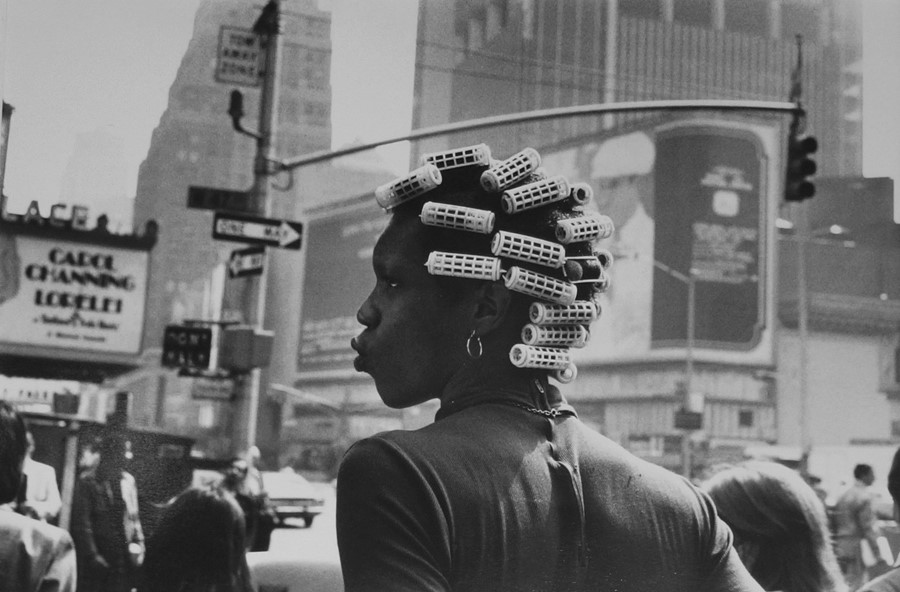

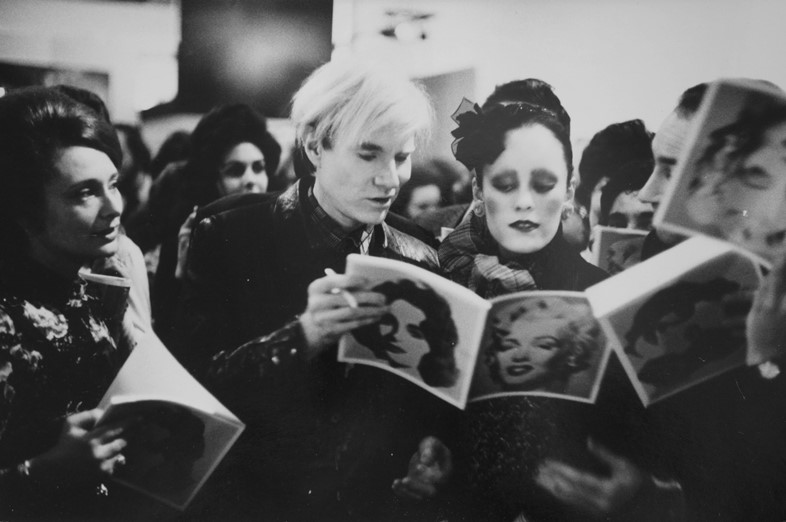

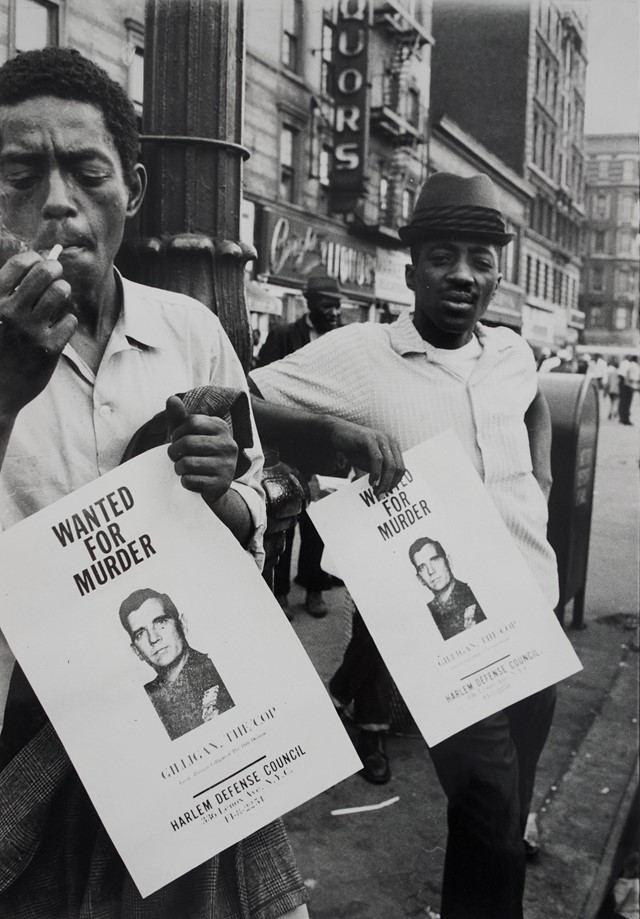

Over his almost 60-year career photographer Neil Libbert has shot everything from the Brixton Riots to George Best, a young Helen Mirren, the folk working at a DHSS Benefit Office, and children playing on the streets of Harlem in the 1960s. Whatever his subject and whenever it was shot, Libbert’s knack for capturing those tiny moments that tell a thousand stories make each photograph as brilliant and revelatory as the next.

Libbert was born in Salford, and initially studied graphic design at college before leaving to pursue a career as a freelance photographer. “I had a keen interest in watching and observing people, a witness to events,” he says of why he chose his medium. One of his first features was a series about homelessness for the Manchester Guardian. From then on, the photographer frequently returned to subjects highlighting poverty, inequality, and institutional failings, working for the likes of The Guardian, The Sunday Times, The New York Times, Illustrated London News and The Observer, who he still shoots for to this day.

London’s Michael Hoppen Gallery is currently exhibiting a section of Libbert’s oeuvre, focusing on earlier images from the 1950s and 60s as well as some prints that have not previously been shown. From such a vast body of work, it must be an interesting process to reflect on work from such a different time in both his career, and in the world itself. Are there any favourites that have emerged in that process? “Some are a little better than others, but for me it’s the latest stage in a journey,” says Libbert, “so looking back I see little difference between early work and what I do today. It is still about the power of observation, and one is just a witness to events. Maybe I haven’t taken a favourite yet.”

Much of Libbert’s reportage is striking in its revelations of difficult and violent circumstances that were otherwise inaccessible. Not only is he skilled in photography, but in subterfuge. “What I do is often on the border between being an intruder and an observer – it’s called clandestine photography,” says Libbert. “I’m not always proud of how I behave but sometimes it’s the only way.”

Today, the idea of street photography is thoroughly engrained in our cultural lexicon, and the fact that most people have the means to take a photograph anywhere, at any time, means that sort of instantaneous image-making is ubiquitous. But as has been noted time and time again, just because someone can take a photograph doesn’t necessarily mean they’re a photographer. “Either you’ve got it or you haven’t. Most pictures taken on iPhones are pretty trivial. There was an exhibition at the Saatchi gallery just recently of selfies, and it was all too much, just banal.”

The proliferation of images and image-makers heralded by technology is just one of many huge changes Libbert has seen his medium undergo over the decades. From a commercial standpoint, he’s also quick to mention how much harder it is to get work published today than 50 years ago. “Magazines and newspapers only want to sell fashion and food, and television has taken over the role of the photojournalist,” he laments. “Also black and white images have a power that colour cannot match, and nowadays everyone wants colour.”

So what does he think makes a brilliant photograph? “I wish I knew…” says Libbert. “It has something to do with the coming together of composition, light, subject matter, or as Cartier-Bresson said, it’s the ‘decisive moment.’ There are no rules.”

Neil Libbert runs until July 21, 2017 at Michael Hoppen Gallery, London.