As a new book is released documenting the artist's 35-year career, he tells Grace Banks about using his practice to democratise political art

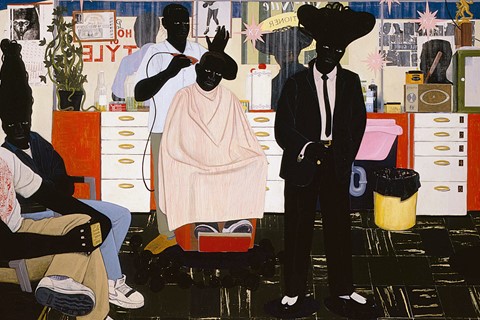

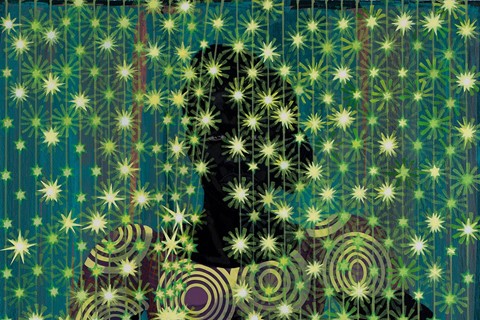

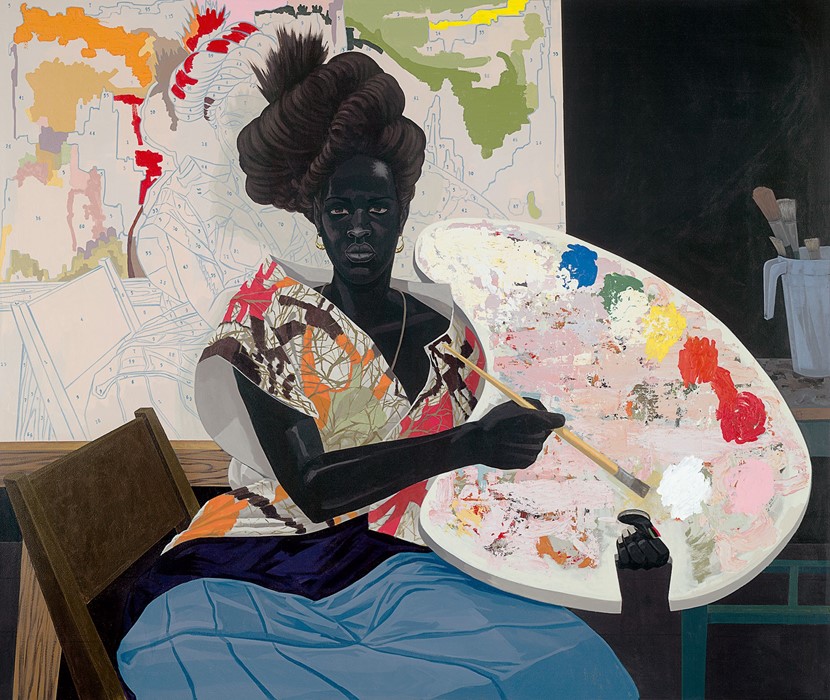

There was a time when Alabama-born painter Kerry James Marshall didn’t think his art was going anywhere special. Knocking around Los Angeles just after finishing art school in 1980, he describes his practice at the time as “pushing paint around”. But then a pivotal moment changed things. “I had a time of reckoning that felt like all the art history, cultural interests and political leanings that I’d always held close came together,” he says. “I needed to reset my priorities and work out what the point of making art was.” He then painted A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980), which, with its references to Renaissance art, Dutch 16th century painting, and the racial stereotype confronting use of African American skin painted near black, was the mission statement of what is now Marshall’s renowned oeuvre. The painting appears in the new book Kerry James Marshall by contemporary artists Charles Gaines, Laurence Rassel and Gregory Tate, the first major survey of Marshall’s 35-year career, which includes research photographs, early drawings and artist interviews with each of the authors.

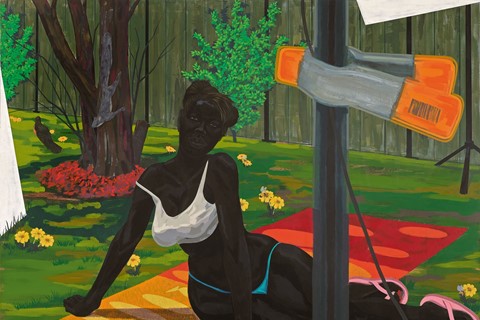

Marshall has spent his career reflecting the overlooked status of African Americanhood through figurative painting. In his groundbreaking A Portrait Of, he riffs on racist stereotypes: “it’s that saying of only being able to see a black person’s teeth and white shirt, their skin is so dark,” he says. In Better Homes Better Gardens (1994), a collage format knits together the artist’s creative influences, “Giotto, Frank Stella, Miro, Matisse,” to criticise the failure of the housing project system; as a young couple walk through the Wentworth Housing Project, Chicago, Kerry uses a Renaissance-style composition to attribute them with a sense of grandeur society won’t. In Voyager (1992), he paints the real life story of a boat that was covertly taking African people to the US to be sold as slaves, and in Portrait of John Punch (Angry Black Man 1646) (2008) he brings the story of escaped slave John Punch in to the modern angry black man narrative.

Marshall’s currently touring retrospective Mastry opened at the same time the Black Lives Matter movement gained traction in the US, and won Marshall a new generation of politicised, die-hard fans. He says he doesn’t take the knee-jerk route of trading on disenfranchisement, “or even the disadvantage of history”, but his experience of studying art in 1970s Los Angeles and the Black Power movement of that time have influenced his work. His politics manifests itself in what he describes as “just doing it. Just showing the mundane and extraordinary of how African Americans exist in the world.” The painting Untitled Club Couple (2014) is the perfect example. A young couple sit drinking cocktails in a bar as the man prepares to propose, a happy image of African American life rarely seen in media imagery.

In an art world where artists regularly embrace lofty icon-like status, Marshall does the opposite. He uses his fame to bring the audience, many of whom are African American, closer, and democratises the nature of political art. “What I hope Mastry ends up doing is completely undermining or doing away with the notion that artists are a savant, that they do things that can’t be articulated, driven by inner turmoil they don’t have access to.” Marshall’s work creates a world free of the white agenda. “The history of political movements in the African diaspora is that the solution to the problem is never in the hands of people who are advancing the movement,” he laments. “I try and operate on my own terms.”

In the first four days of the Trump administration, Marshall drew a few social commentary comic strips, “but for me, that’s not fruitful”. He wasn’t surprised by Trump’s election win. “The US was founded as a white supremacist nation, that’s just what it is,” he states. Trump won’t impact his art, he’ll carry on as he always has: doing the work, putting the hours in. “There’s nothing more special than intellect and labour that makes painting work,” he says. “There’s no magic there, it’s information and it’s work.”

Kerry James Marshall is available now, published by Phaidon.