The launch party for John-Paul Pryor’s visceral debut novel took place recently in a crowded Kings Cross gallery surrounded, appropriately, by the twisted fairy-tale art of Wolfe von Lenkiewicz.

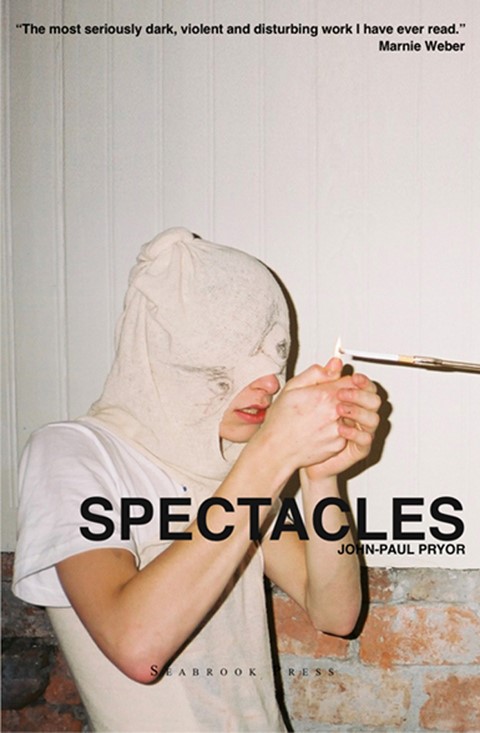

The launch party for John-Paul Pryor’s visceral debut novel took place recently in a crowded Kings Cross art gallery surrounded, appropriately, by the twisted fairy-tale art of Wolfe von Lenkiewicz. Carrying home a copy of Spectacles that night felt like getting your hands on one of those green-jacketed, transgressive titles from underground publisher Olympia Press. Emblazoned with artist Marnie Weber’s warning (“The most seriously dark, violent and disturbing work I have ever read,”) a dive between its covers reveals an atrocity exhibition that would be relentless if not for Pryor’s lyrical romanticism. Partly inspired by John Keats’ poem Lamia, it was written in 30-hour stretches, tuned in to the shadowy dreamworld that emerges from the masonry at nightfall, everyone a potential murderer or victim.

Set in a Ballardian future, London is a living ruin of bio-scares and death gangs, genetic modification and chemical attacks, its population glazed with a cocktail of drugs. While the elite triple their life expectancy inside gated communities, an invisible underworld rubs up against them, with its own hierarchy of prostitutes, pimps and drug addicts, the maimed and disfigured who inhabit the yawning abyss of “the hole”. In hallucinatory flashes, the voices of a handful of characters are weaved together, from the reigning queen of this nu-world – a red-haired television presenter – to a 14-year-old prostitute who is slowly shedding her skin. Pryor’s poetic mixture of raw violence and transcendence is reminiscent of another debut – rebel outsider Jean Genet’s tale of the Montmartre criminal underworld, Our Lady of the Flowers. Like Genet, he trawls the depths of a nightmare, finding beauty in his children of misfortune. AnOther put the young novelist in conversation with author Henry Hemming, whose book In Search of the English Eccentric unearthed modern “witches”, Hells Angels, a reincarnated King Arthur and a suburban dominatrix in a journey into the heart of Englishness. The pair met in Soho to talk about magical realism, finding beauty in the dirt, and why there’s nothing more life-affirming than having the shit kicked out of you...

Introduction by Hannah Lack

Henry Hemming: Tell me about where you see Spectacles in a literary sense. Is it part of a lineage of transgressive literature?

John-Paul Pryor: I suppose it fits into that vein. I’ve always been interested in writers like Jean Genet, Hubert Selby Jr... They’ve both been massive influences. I’ve always liked people like Atwood and K Dick too, and magical realist literature. I think Hesse’s Steppenwolf is one of the most potent novels I’ve read. It really hit home.

Henry Hemming: What was it that made it hit home?

John-Paul Pryor: It’s to do with feeling like an outsider: feeling like there are stranger things in heaven and earth and all that, and getting closer to that sense of the sublime through the act of finding things out as you go – allowing a feeling or atomosphere to sort of drive you on. But really what I’m looking at In Spectacles is darkness, and what’s there in the darkness. I’m fascinated by why people are so fucking horrible to each other.

Henry Hemming: There’s quite a lot of that in the book – violence, rape, murder and transgression more generally. Has the process of writing about any of this changed the way you see it?

John-Paul Pryor: It’s such a cliché to say it, but there is a catharsis in there. One of the main characters has OCD, as I did when I was a child. And a lot of the things I fear the most are places I wanted to take the reader to, or put myself in, partly so I wouldn’t be so afraid of those things, I guess. But all of the things I describe in the book exist. Think of the Ipswich prostitute murders or Baby P. The mainstream media creates an anxiety around these things without ever actually talking about the fact that it’s human beings who commit these crimes. I’m interested in that notion of the collective consciousness – that we’re all capably murderers, we’re all capably rapists, we’re all capably whatever.

Henry Hemming: Were the colours in the book important to you? You have a strong emphasis on the monochrome –the image of the white dog charging across a field of black poppies, for example.

John-Paul Pryor: I dream in colour but I definitely saw most of the images in the book in a monochrome.

Henry Hemming: Many of the characters seem to be seeking out the sublime to expiate a feeling of self-loathing. When you look around you now, in London, do you see a lot of self-loathing?

John-Paul Pryor: I see people who probably should hate themselves more than they do. I suppose I do have an innate hatred for a lot of things. But I also am a person that really longs for peace and tranquility. I can’t actually watch a film like Saw, or some other trashy horror films. They freak me out.

Henry Hemming: Why is that?

John-Paul Pryor: I don’t know. There is a part of me that’s terrified of violence and what people can do to each other. I think you can reach the sublime through combat or violence, though. I suppose that’s part of the drive in us as human beings. If you’re a boxer and you win a fight the adrenaline comes as much from the punches you’ve thrown as the ones you’ve survived, right? Someone once said there’s nothing more life affirming than having the shit kicked out of you. I can see that. There is this head-state you enter after you’ve been beaten up that’s rare…

Henry Hemming: Is it sublime? That head-state?

John-Paul Pryor: In a sense, but I wouldn’t advise it as a life choice…

Henry Hemming: How else can you reach the sublime?

John-Paul Pryor: If I really want to get high, I will just fast. Eventually, you get to the point where your body starts eating itself but the mind feels so awake. I don’t think you can get to that state through any kind of drug use. Most drugs have more of a dulling effect.

Henry Hemming: There is many a holy man who would agree with you! Is this the state you’re in when you write?

John-Paul Pryor: I write through the night, and then come back to it, edit it, chop it up… replace certain sections of it. It was mostly written in these long stints of 30-plus hours on black coffee with no food and no sleep. I’d get to a point where I felt almost psychotic.

Henry Hemming: In the book you talk about beauty and our attempts to attain it being psychotic, what interested you about that?

John-Paul Pryor: I think it’s a fascination with genetic modification. I’m interested in notions of beauty – how we define it and how at its core it can be completely awful and rotten and full of self-loathing, a bit like the fashion industry. These things affect us profoundly. In the book I wanted to explore this idea that we’ll end up with gated communities of sculptured perfection next to slums. But perhaps in the dirt is where you’ll find the true beauty. By peeling off of the skin, taking away the eyelids and turning everything inside-out you find this pure, archetypal light inside you – even if you’re absolutely terrifying to look at.

Henry Hemming: In the book there’s a woman who signs up to a website called strangersinthedark.com for anonymous masochistic sex. What do you think of the fact we are edging towards a state in which we acknowledge the prevalence of sexual desires that might not make sense to everyone?

John-Paul Pryor: I’m aware of it but I’m not sure if it is a good thing. I think there’s a degradation of the soul that comes about through things like pornography, but obviously these are releases as well. They are transgressions, but transgressions often require victims, and I’m very aware of the victims. As I was writing the book the whole thing began to have a life of its own, and I was getting so involved in those characters that I ended up feeling an intense love for some of them, and a hatred for others. In a sense, it became an opportunity to kill the people I hate most in society.

Some time ago, I saw a woman give a speech describing how her daughter had been raped and murdered on Halloween, and how in the particular state in America she was from, she could choose whether the murderer got the death penalty. Instead of having him electrocuted she went to meet him and their parents, which is obviously an incredible humanistic act. I could not do that. I have a rage inside me. If someone raped and killed my daughter I think I would be able to cut them into little pieces, put them in a box and chuck them in a river.

Henry Hemming: In a way, for that mother to meet that family is an even more extreme transgressive act isn’t it?

John-Paul Pryor: Yes. Absolutely. It blew my mind.

Spectacles is out now.