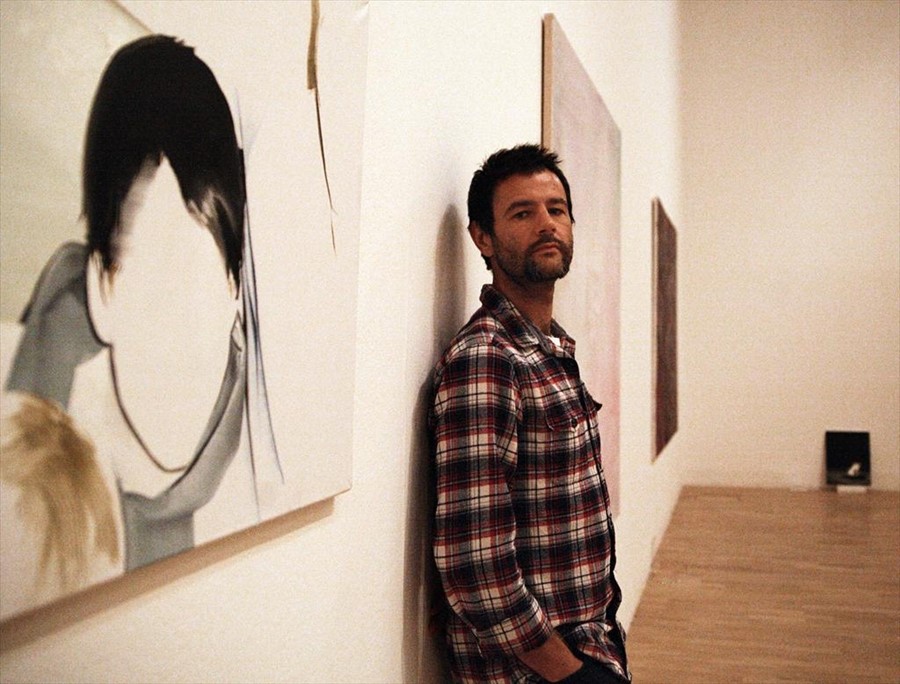

Polish artist Wilhelm Sasnal’s mysterious pallid canvasses have made him the young superstar of contemporary painting. Whether he’s making portraits with smudged out faces, gloomy landscapes, sharp geometries or thickly smeared abstractions, he’s

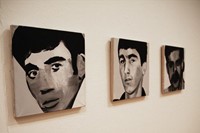

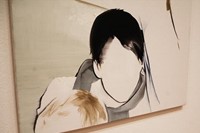

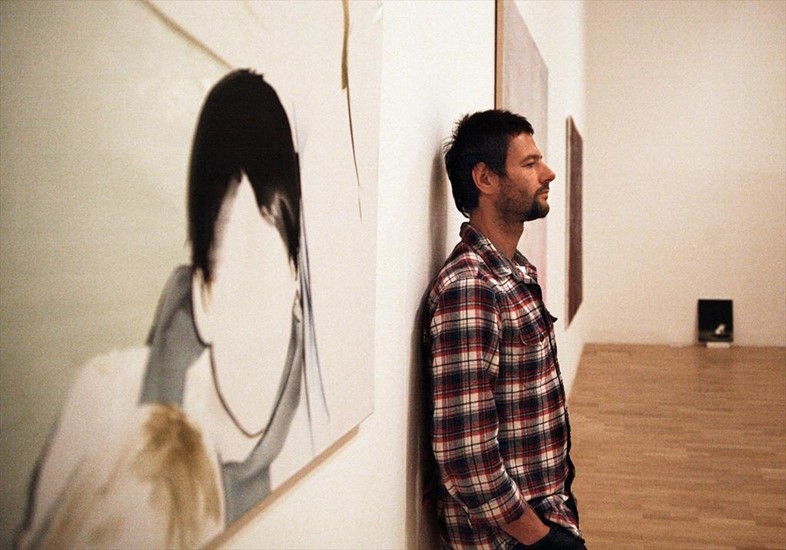

Polish artist Wilhelm Sasnal’s mysterious pallid canvasses have made him the young superstar of contemporary painting. Whether he’s making portraits with smudged out faces, gloomy landscapes, sharp geometries or thickly smeared abstractions, he’s consistently interrogated the pictures that surround us. There’re his Pop-infused early works that aped advertising imagery in the wake of the fall of communism. Or the famed Maus series, where he blew up the cross-hatched background scenery from Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning holocaust comic, and transformed it into bold graphic paintings in harsh monochrome. And of course, the more recent works based on personal snapshots, images from old books, the Internet and newspaper stories alike. Sasnal’s quietly disturbing interpretations of familiar or humdrum subjects unleash slumbering histories and buried traumas – like the the industrial farming Polish pigsty that suggests a concentration camp gas chamber, to quote a recent example. AnOther caught up with him in the run-up to his major survey, opening this week at London’s Whitechapel Gallery.

You’ve said many times that music was really important to you when you first started painting. Music can really be part of the present moment like nothing else. Was that something you were interested in bringing to painting?

I think music really responds quickly, instantly for the needs of young people. I was younger then. I wanted to be part of the fans. It just worked. I didn’t wonder why. And there’s a strong link between artworks and music, like The Smiths’ graphic design and Bauhaus or using a still from a Warhol film.

Do you listen to music while you paint?

Yes, it’s still important, but I listen much more to classical music as well. There is a Polish radio station that I really like, it’s just like Radio 4.

Do you work on several canvases at once?

No, it’s always one painting. Sometimes I go back to it, if I don’t like it I recycle and paint over the old paintings. I’ve started putting canvasses together. I don’t have many paintings around me, usually just one.

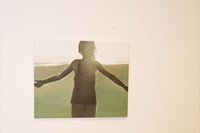

The size of your work changes as much as style. Of the two most recent paintings in the show, for instance, Tsunami is more intimately scaled and Pigsty is huge.

In Tsunami, the drama of this girl, surrounded by debris, it’s more elegant at a smaller scale. The other way around, what I liked about Pigsty, is that it’s a stinky filthy unimportant subject painted on a big canvas. I remember, in my hometown, there were villages with pigstys and when the wind blew from the east, it really stank. I felt that subject should be that huge.

Of course that painting makes one think about the holocaust as well.

Yes.

Your paintings often depict faces that have been smudged, blocked out or otherwise obscured, is that mystery you bring to them to do with restoring a freshness to how we see?

I realised, not with the painting, but when I was drawing comics, that whenever I tried to make up a character, it always looked like a caricature. So I left the face blank. I like that when don’t have particular features, you can imagine whatever you want. I like mystery, at least in terms of art. That’s why I don’t paint faces.

Have you seen Gerhard Richter’s Tate show?

I realise now where I’m from. Not just for me but for a whole generation of painters of my age, he’s like the Velvet Underground for musicians.

Who do you talk through all your ideas with?

My wife is definitely the one. From the very beginning. Actually I started painting not long before I met her. We somehow grew up together. She used to come to the studio and tell me what’s good, what’s wrong. And so she does still.

Is she an artist?

No, she studied literature. But we’ve started doing films together.. In the last couple of years we started getting into proper feature length films. We’re planning the next one now. She writes and we direct together.

OK, the obvious question. What do you think keeps people coming back to painting and why does it endure?

It’s a natural activity. It’s very primal. Drawing is very primal. I think images aren’t important because of the numbers that surround us. But painting has a chance. There is always painting, like there’s song. I don’t think it needs speculation as to whether it is alive or dead.

Wilhelm Sasnal, Whitechapel Gallery 14 October 2011 – 1 January 2012 www.whitechapelgallery.org. The exhibition is part of I, CULTURE, the international cultural programme celebrating Poland's presidency of the EU. For more information visit www.culture.pl

Text by Skye Sherwin