A new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC shines fascinating light on the multi-faceted writer and poet through a rare collection of artworks, images and objects

To be familiar with the poetry and writing of Sylvia Plath is to be familiar with Plath herself. The American wordsmith bore all in her work, plumbing the depths of her own character and experiences – from her mental health struggles to the breakdown of her marriage – with astounding candour and inimitable lyricism. Her writing is intensely visual, and gloriously descriptive. “What I fear most, I think, is the death of the imagination,” she wrote in a telling journal entry in February 1956. “When the sky outside is merely pink, and the rooftops merely black.” This desire to express what she termed her “visual imagination” was not confined merely to words, however: a lesser-known, but equally prolific portion of Plath’s output consists of drawings, paintings and other artworks carried out throughout her lifetime. Now, a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC brings together a compelling array of such pieces, alongside personal letters, family photographs, and various other objects, to offer an enthralling and dynamic exploration of Plath’s visual creativity, and how she employed it in the shaping of her own identity. Here, to celebrate the exhibition’s opening, we catch up with its co-curator Dorothy Moss to discover some of the fascinating facts the show’s artefacts reveal about Plath’s personal life and her shrewd understanding of visual media.

1. For Plath, drawing was not merely a hobby but a necessity

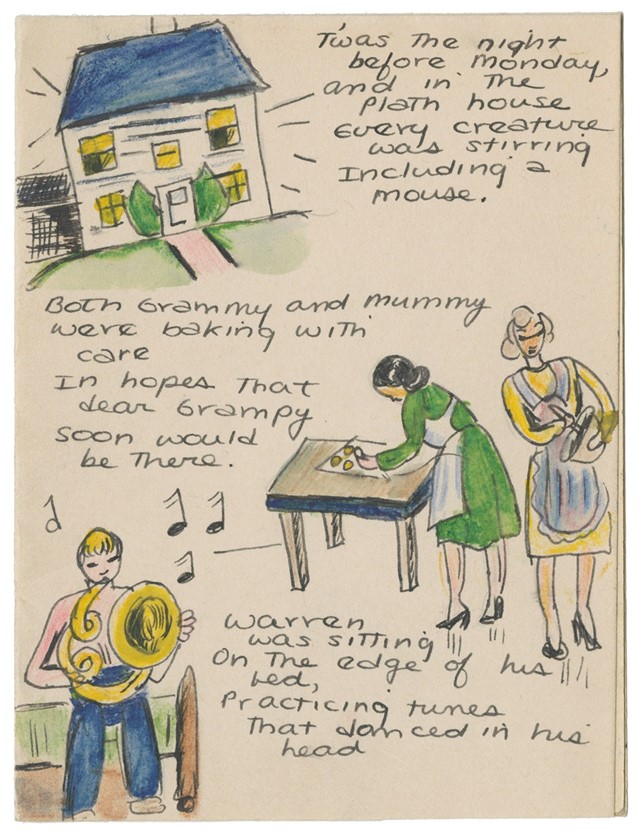

“To compile the exhibition, Karen Kukil [the show’s co-curator] and I looked to the vast collection of items in the Smith College archive, which span the years Plath spent at the college right up to her death in 1963,” Moss explains over the phone from Washington. “We also scoured the collection of journals, letters and keepsakes that her mother saved and then sold to the Lilly Library at Indiana University. Prior to this I knew that Plath drew and sketched but it was only looking through this rich material that I realised that it wasn’t that she loved to draw: she had to draw.” This, the curator explains, extended from sketches of her family doing household chores to doodles in the margins of her books to pictures illustrating the many letters she sent to friends and family throughout her life. “This aspect of her personality – this concept of Plath as an artist, which is not as well known or developed as how we know her as a writer – was a main motive behind the exhibition.”

2. In fact, she wanted to pursue art instead of writing but was persuaded otherwise

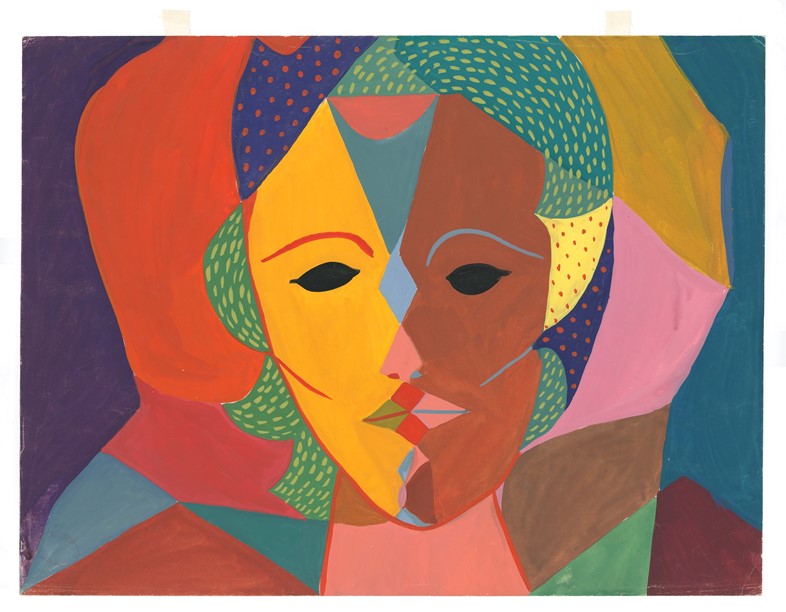

“There’s an amazing painting Plath did at the end of her high school years called Triple-Face Portrait,” says Moss of a striking, almost cubist work depicting a woman’s face made up of individual, multi-hued shapes. “You can see how sophisticated she was in terms of her use of colour and her understanding of design and graphic elements.” Shortly after completing the work, the teenage Plath enrolled at Smith College where her first choice of major was studio art. “But she was such a brilliant writer that her professors encouraged her to major in English instead,” Moss expands. “I always wonder if she felt conflicted about taking that path rather than an artistic one, but she never gave up drawing; it was always there.”

3. Plath’s early artworks chart many of the characteristics that would come to define her

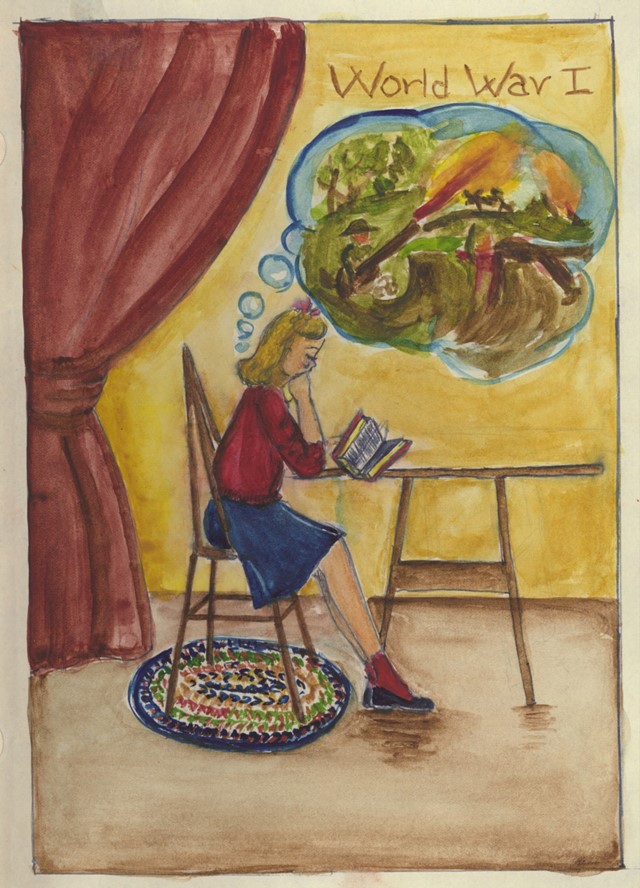

Moss and Kukil were intrigued to discover that many of Plath’s youthful creations served as precursors to her future interests and traits. “On the title page of an essay she did in junior high school, entitled A War to End Wars, Plath included a drawing of herself writing at a desk with tears streaming down her face and a thought bubble above her head depicting soldiers in combat,” Moss says. “I thought that this was significant to include because Plath was a pacifist throughout her life. Both of her parents were against war and she herself was very sensitive to anything that had to do with violence. Later she spoke out about those issues publicly – she published an early piece about ending war in the Christian Science Monitor and then, when she was a young mother, she marched against nuclear weapons in Trafalgar Square.”

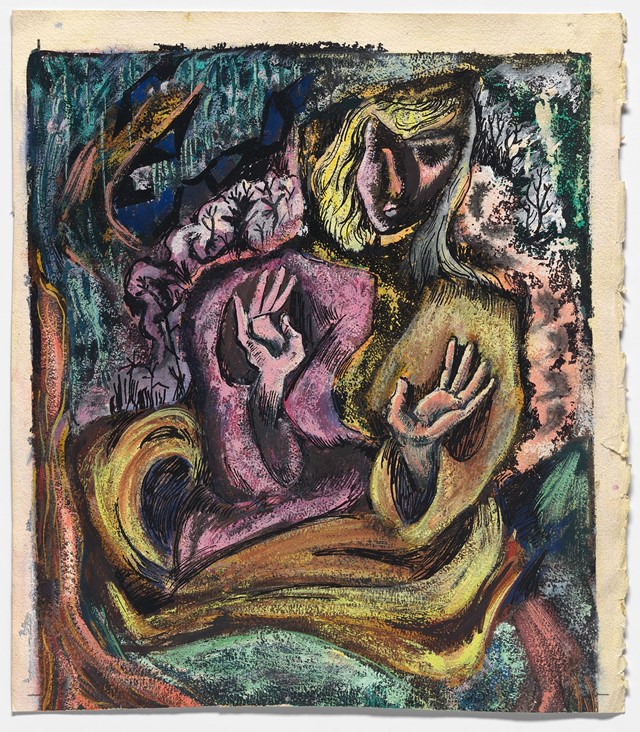

One of Moss’s favourite artworks included in the show is a semi-abstract self-portrait done by Plath between 1946 and 1952, showing the artist seated, arms raised, palms facing the viewer. “It’s quite dramatic and has an almost surreal quality to it – when I first saw it in person I was struck by the intensity of emotion that Plath captures, and by her technical skill. But also what’s interesting is how prominent her hands are.” Plath’s hands and the gestures she made with them, the curator says, were a signature trademark of the poet. “Later in her life [her husband] Ted Hughes wrote a poem about her hands, so they were clearly very much a part of her visual presentation. In the exhibition we’ve hung this sketch alongside a contact sheet showing Plath in conversation with fellow poet Elizabeth Bowen, where you can see she’s using her hands very forcefully – it’s a wonderful echo.”

4. Plath’s relationship with her parents was tender but turbulent

Much can be deduced about Plath’s family life from her writing and drawings, a point that Moss and Kukil opted to expand upon with objects and images. “I wanted to include an image of Plath's father, because he died when she was only eight,” Moss says of an early photograph depicting a tiny Plath sitting alongside her parents. “After that she set out to find him again through memories and writing – a lot of her poems are about him. She was angry with him for being gone but desperately missed him throughout her life; it became a key part of her identity.” Another inclusion in the show is Plath’s ponytail, chopped off by her mother, Aurelia, when Plath demanded a pageboy crop aged 13. “I was interested in what that hair signified for her mother,” says Moss. “She had saved it in a box, alongside a sweet note explaining how she couldn’t sleep the night before she cut it. Plath adored her mother but she always put a lot of pressure on herself to do well for her. It was something she struggled with, and wrote and talked about a lot. At one point her psychiatrist said, ‘I give you permission to hate your mother’. So it was a fraught relationship but also a very tender one.”

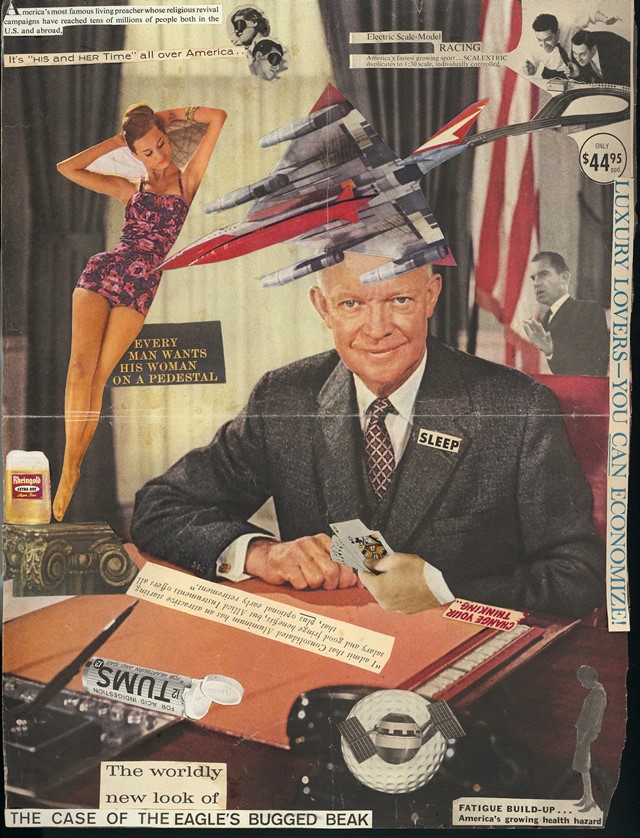

5. Plath was a secret collage artist

Among the many artworks by Plath on display, perhaps the most surprising is a distinctly Pop Art-esque collage comprising images of Eisenhower and Nixon, a pin-up girl (alongside the text “every man wants his woman on a pedestal”), a packet of Tums (antacid medication) and a bomber jet, among other things. “She did a lot of these,” Moss explains. “She created visual art out of anything she could find; her mother would send American magazines to her in England and so she made collages with the imagery. First off, this work shows her inclination towards design and colour, and of course it’s loaded with symbols – anti-patriarchy and anti-war messages – but it also has funny little touches like the Tums wrapping that show her whimsical side, as well. I really wanted to offer a complete picture of Plath in this exhibition. I think we often associate her with a more intense, dramatic spirit but she had a wonderful sense of humour and could be very joyful and lighthearted.”

6. Plath was a woman of many sides

“Plath was very aware of all her identities and how to present them visually to serve herself well in her professional life, as well as in her friendships and her role as a daughter, a mother and a wife,” says Moss. This is something that Moss and Kukil have sought to demonstrate throughout the display. The first wall you encounter upon entering the exhibition shows various photographs of Plath in different guises, which, Moss explains, were carefully chosen to introduce this idea. “In the centre of the wall is a photograph by Rollie McKenna – a 1959 gelatin silver print, which depicts Plath with a deep, introspective expression. Then on one side of that we hung a photograph of her on the beach with platinum blonde hair, looking like Marilyn Monroe, which was taken by a boyfriend in 1954. On the right side, conversely, is a studio photograph of her with brown hair which she submitted with her Fulbright application to Cambridge; she had it dyed brown to look more studious. So she was very interested in self-fashioning.”

7. But such self-scrutiny came at a cost

Unfortunately Plath’s self-consciousness and the pressure she put upon herself to present the “correct” facade in any given situation also caused her much distress. “There’s a journal entry from 1953 that includes a cut-out photograph of her face with the inscription, ‘Look at that ugly dead mask here and do not forget it,’” says Moss. “We find her struggling in such moments to role-play appropriately as she navigated the sometimes oppressive pressures of society.” This concept is compounded in another diary entry from 1952, where Plath asks, ‘How can you be so many women to so many people, oh you strange girl?’ But, Moss continues, it is just this ability to convey different selves and employ such different voices that made Plath so unique, and her legacy so enduring. “Looking at all the material included in the show, you can tease out a very complicated, brilliant personality who was constantly battling to achieve a sense of self, in a variety of forms. We rarely get such a private view of such an influential person working through their own struggles with identity.”

One Life: Sylvia Plath is at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, until May 20, 2018.