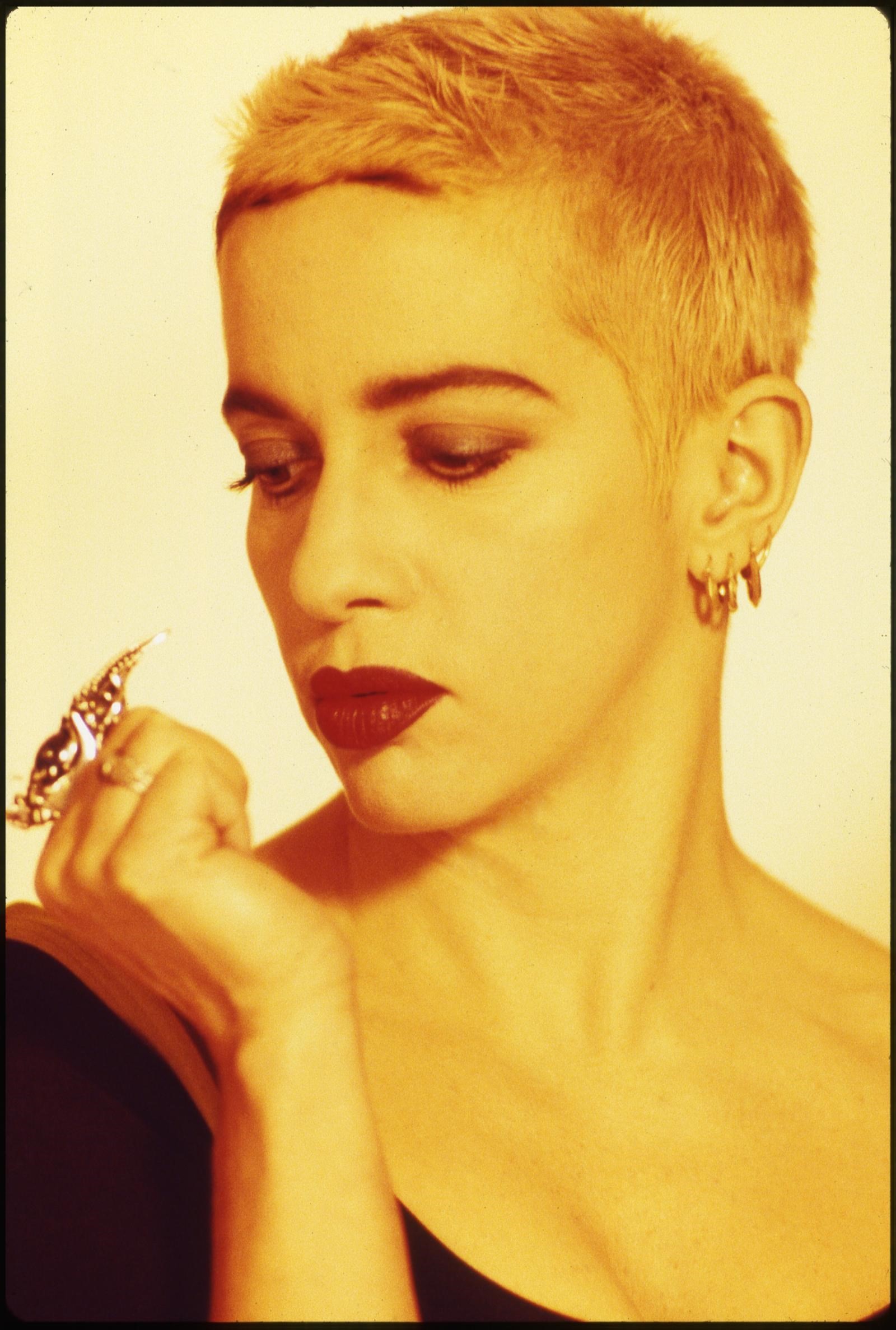

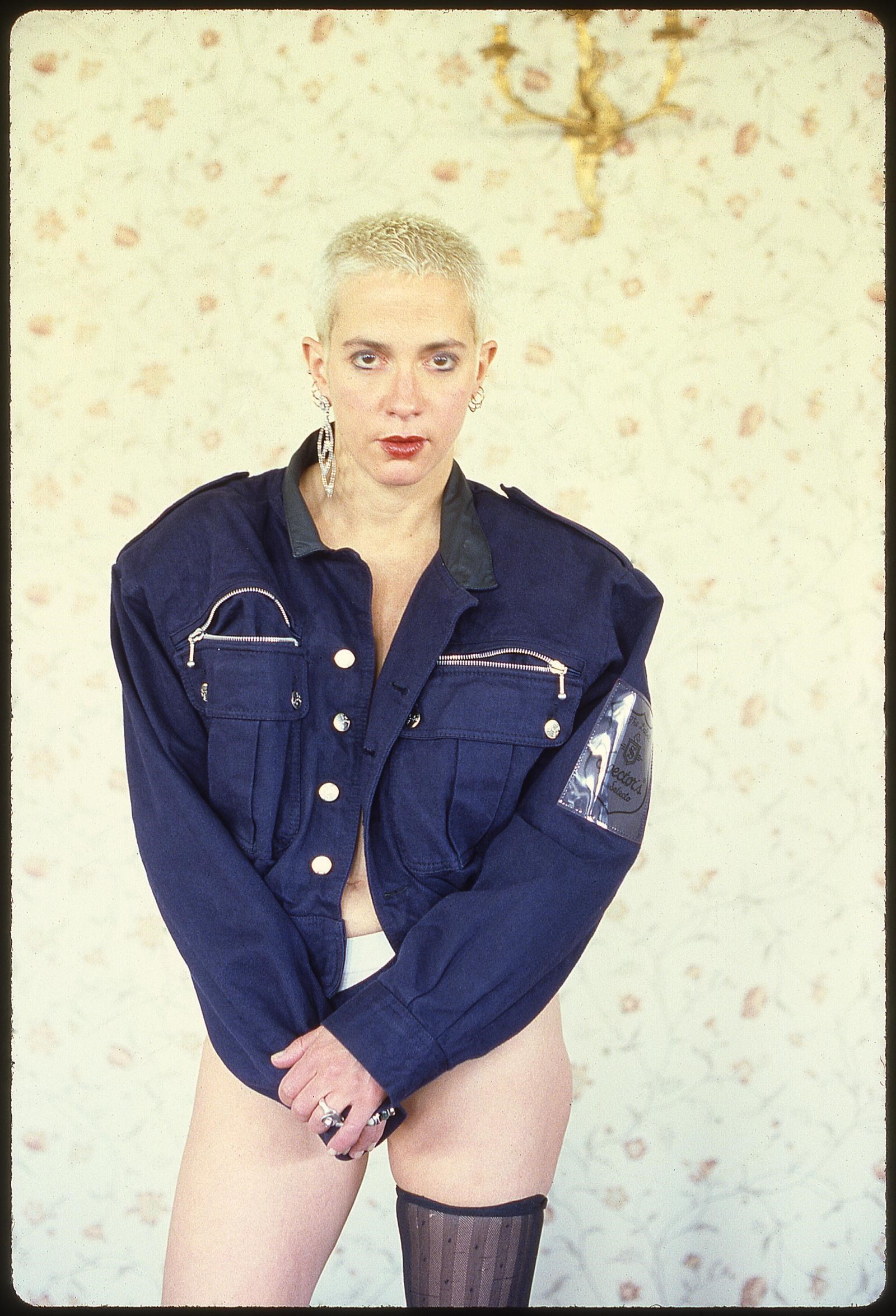

Until her untimely death in 1997, post-punk icon Kathy Acker terrorised the literary scenes in New York and, later, London with novels that mixed raw, diaristic writing with formal innovation and searing intellect. At the height of her career, she achieved the kind of cross-over fame that other writers could only dream of. Yet by the end of the 90s, the image that she had created for herself – the peroxide blonde crop, extensive tattoos and gothic wardrobe – had largely taken over scholarly reading of her work.

In After Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus, author of the cult novel I Love Dick, makes a persuasive argument for why we should be taking Kathy Acker more seriously. I caught up with her via Skype to discuss autofiction, the myth of the genius and how to write a truthful biography.

Chloe Stead: After Kathy Acker opens with the scattering of Acker’s ashes, but before the reader is given a picture of what happened there, you warn us about the fragility of these memories. What was your decision process in starting the biography this way?

Chris Kraus: Writing a biography – like writing any history – is highly subjective and everyone has a different version of the same events. So I wanted to capture that fragmentation of perception in the way that the story was told. That seemed to be the only truthful way of writing a biography, to say right up front how specious it is. This is my version of Kathy’s life. Any other biographer would have a completely different version.

CS: You refer to your own memories of Acker only once in the book, when you briefly mention that you saw her read at the legendary Mudd Club in 1980. Was that a conscious decision on your part?

CK: My goal was to never use the first person at all. I think I used it maybe three or four times in the whole book and when I do it’s a very reportorial eye. In my first three novels, I Love Dick, Aliens [and Anorexia] and Torpor, [I] cover my life during some of those same years, the late 70s and 80s, and I said everything I needed to say about myself in those three books as a participant or non-participant of those scenes. I didn’t know Kathy, we didn’t have a friendship, and it would have been really presumptuous, I think, to put myself in the story.

“I wanted to capture that fragmentation of perception in the way that the story was told... This is my version of Kathy’s life. Any other biographer would have a completely different version” – Chris Kraus

CS: Can you remember the first time you came across her work?

CK: I discovered Kathy’s work years before I ever knew I’d be a writer, but it was extremely important to me. It was all over the East Village in the self-published and small print editions, and I inhaled those books. They went straight to my heart. I felt like she was in my head and speaking for me. It was very, very powerful. I wasn’t thinking of it really in the context of literature. I was thinking of it in the context of how does it feel and what does it mean to be broke and lonely in New York City and having all of these terrible relationship experiences.

CS: How did this relationship change through writing the biography?

CK: I came to appreciate her work in a way that I never had the first time around. I was really impressed by the collision of purely formal strategies that she used and the very primary diaristic, emotional writing that becomes part of the assemblage. I think that was one of the great, original things about Kathy’s writing. At one point in the book I go back to the Burroughs blurb: “Kathy Acker gives her work the power to mirror the reader’s soul.” So I asked, how did she do this? That’s quite an achievement, but how did she do it?

“I inhaled those books. They went straight to my heart. I felt like she was in my head and speaking for me. It was very, very powerful” – Chris Kraus

CS: What do you think of Acker’s current status in the literary world?

CK: I think that she’s about to come back. I think she’s about to be read really seriously as the writer she deserves to be, as the writer she was. Towards the end of her career she really fell off the map in terms of the literary world. I write about that in the book, [about] how she felt she was being eclipsed by all her contemporaries who were getting these serious and excellent New York Times reviews for their work and meanwhile people are just talking about her tattoos and her haircut. I mean, she wasn’t a victim, she was partly responsible for advancing and perpetuating those mythologies, but it did come at the expense of readings of her writing.

CS: What do you think a rediscovery of Acker’s work might do for the current literary scene?

CK: I think it’s going to do a lot to change people’s false perceptions that this ‘genre of autofiction’ originated because of the Internet. It’s ridiculous! [Laughs] Autofiction is a French tradition, it goes way back into to the 20th century and Kathy was picking up on the French Modernists. There’s a whole tradition of narrative work that does not conform to a Hollywood five act narrative arc, which has become the given now for literary fiction in the US and the UK.

“Kathy was wildly contradictory, like anybody. She’s constantly longing for community and lamenting the lack of community but every time she finds herself within a community the first thing she does is compete with people and sleep with their boyfriends” – Chris Kraus

CS: Something that’s quite surprising about the biography is how often Acker appears as an unsympathetic character.

CK: Kathy was wildly contradictory, like anybody. She’s constantly longing for community and lamenting the lack of community but every time she finds herself within a community the first thing she does is compete with people and sleep with their boyfriends. So there’s an inconsistency there, and I think it’s a terrible thing that we still expect a consistency of women that we don’t expect of men. Women would be criticised for inconsistency whereas in a male writer or thinker it’s an admirable part of a nuanced picture of a person.

CS: I read that you already started conducting interviews with Kathy’s friends and colleagues shortly after her death in 1997. Did you know at the time that you wanted to write an autobiography about her?

CK: Yes, but I would have written it in a much more fan girl way, emphasising with Kathy in ways that were really not appropriate. I published some pieces about Kathy around 1998, 1999, 2000 and the tone of them is much different. I was just wildly identifying with her. I was extremely moved by her death in the clinic in Tijuana. I was somewhat in the loop when that was happening because I was friends with Matias [Viegener] who was caring for her, and I was really shaken and radicalised by that. If I had written the book sooner it would have been wrong. It would have been too incestuous; I probably would have been more in the book. I wouldn’t have had the distance needed to really take apart her project in the way that I could later.

“I think it’s a terrible thing that we still expect a consistency of women that we don’t expect of men. Women would be criticised for inconsistency whereas in a male writer or thinker it’s an admirable part of a nuanced picture of a person” – Chris Kraus

CS: Much of the biography takes place in 70s and 80s New York; you’ve talked in other interviews about how you wanted to present an alternative view of this mythologised era. What are some of the ways you tried to achieve that?

CK: When I started the book there was a whole raft of memoirs and fiction books set in that era. It seemed so untrue to the New York that I arrived in in the late 70s and lived in during the 80s. So the first thing I did was look for other people who were important participants at the time but who somehow have slipped through the cracks of art history. Some of Kathy’s friends, like the choreographer and dancer Pooh Kaye and the performer and composer Jill Kroesen, their work was all over the place and for whatever reason it hasn’t been swallowed up into that myth. The myth is always so selective and has to do with all the predictable things: with sex, with glamour and people’s work which doesn’t lend itself to that narrative tends to be written out of it. I wanted to cast a much wider net and bring people into the story who belong there. It works against that myth of the artist as a singular genius who exists in a vacuum.

After Kathy Acker by Chris Kraus is available from August 31, 2017 published by Penguin. With thanks to Michel Delsol.