As a new book chronicling their work launches to the world, Billie Muraben speaks with Barber & Osgerby about the variables that define their practice

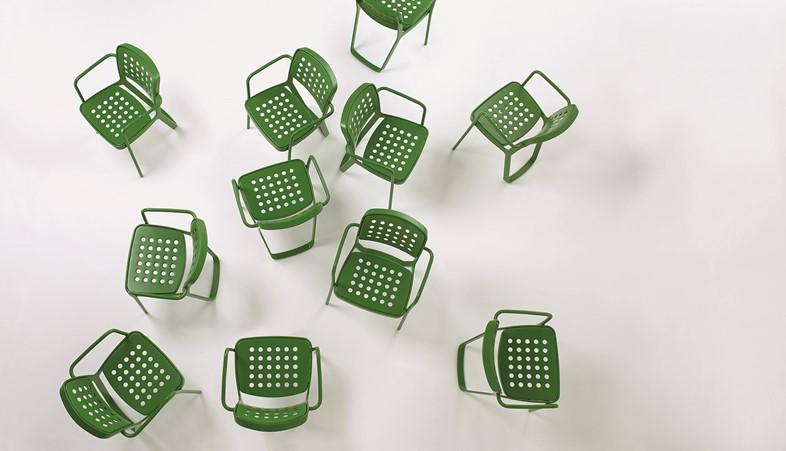

“All artists, designers and architects get published in the end. People want to see what you’ve done,” remarks Edward Barber, one half of industrial design duo Barber & Osgerby. He is speaking of the pair’s decision to take a momentary step back from their practice to work on a monograph, Barber Osgerby, Projects, published by Phaidon this month. “Flicking through a book is so much nicer than scrolling through a website, which doesn’t feel that special. It’s a crafted, physical object, with a screen-printed, fabric cover, rather than a screen, which a minute ago you might have been shopping on.” Their last book was published in 2011, “and we’ve done a lot of work since then – a lot of better known, more involved projects,” his counterpart, Jay Osgerby, continues. “The projects we’ve worked on have become more complex, in a way, more industrialised. Say, the office chair we’ve just done with Vitra, or the Olympic torch.”

It seems a well-timed break; 2016 marked 20 years since the pair first founded their eponymous industrial design studio, in which time the Vitra chair and the Olympic torch are only two in a long line of highly revered design objects to have emerged from their practice. And what better cause for reflection after two decades of work than a substantial, glossy tome documenting it? “It’s not often that you have the chance,” Osgerby continues, noting the links which form between different endeavours when they are viewed together from a distance. “We don’t tend to analyse projects from the past while we’re working. There’s never time. Let alone putting several projects together and analysing them to see what the connection is.” Barber concurs. “We’ve noticed, having done the previous book, that certain themes ran through the work that were quite clear. And actually, current projects we are working on still have a link to the very first projects we were doing, in terms of material, or the language that we’re using.”

The monograph is quite something to behold. Arranged thematically in three parts – ‘Folded Structures’, ‘Frameworks’ and ‘Volumes’ – eachs reflect the physical qualities of the projects contained, and sees the themes unpacked in a corresponding series of essays. The conversations include key figures connected to the pair’s work, like Rolf Fehlbaum, the chairman emeritus of Vitra, design studio Dunne & Raby, or Christopher Wilk, keeper of the furniture, textiles and fashion department at the V&A. “We wanted other people to draw conclusions about the work, and we wanted to find things out about our own work that we were blind to, because we’re too close to it” says Osgerby. As they prepare for the book’s launch, AnOther met with the pair to talk about the book, their practice, and to get to the crux of what drives them.

On making connections in their work...

Jay Osgerby: “One of the things we found out, or became more aware of, is the visual connection between our projects. We tend to think our projects are discreet in terms of the way they look, but they are underpinned by an approach. The book’s contributors have made legitimate connections between them visually, as well as in the approach to them.”

Edward Barber: “We find it hard to see that there is a visual link between each of our projects, because they are so different. You’ve got plastic chairs designed for education and then a Japanese lantern, and then you’ve got the BMW installation, the torch. The materials are all different, the scales are all different, the craftsmanship, or the mode of production is completely different. Yet, people can see a link between all those things, which I’m not disputing, but we find it hard to see that... I suppose it stands to reason that there must be a link, because it’s the same people doing the work.”

On defining their practice...

EB: “The great thing about being a designer, or as an industrial designer as we are, is that we’re collaborators. We don’t just make stuff, we often do that by collaborating with a manufacturer. Whether that is someone in furniture, or making technology, or wallets, or whatever it might be, these projects quite often just appear out of nowhere. One day you’re thinking about designing wooden furniture, and the next you’re working on a really high-tech piece of equipment that has come through the door. There’s that element of the unexpected, which we like.”

JO: “The conventional route is: establish a style and repeat it. Then, because you are the person with that style, you can command higher prices, and you become defined by that way of working. The problem is that you can lock yourself in your own cage, and who wants to do that if you’re creative? We don’t like closing down opportunities, especially creative ones, which is probably why we don’t focus on one specialism. We discovered quite early on how that was confounding for people, they couldn’t understand how you could be doing furniture, and architectural projects etc. We thought, quite straightforwardly, that we would split it off and give different names for each discipline – Barber Osgerby, Universal Design Studio, MAP – but keep everything together, like a college.”

On making the most of opportunities...

EB: “We tend to make more of a situation. When we were asked by the Royal Society of Arts to look at school furniture, all we were asked to do was to assess it and give our advice on the furniture they should use at their academy in Tipton. We realised that there weren’t any good chairs being used in schools. We thought there was the need for a new design, came up with a concept, and took it to Vitra. I was just on holiday in Japan and I’d always wanted to see the lantern factory in Gifu. I went to the company to see the manufacturing, got talking to the owner, and said ‘Well, have you ever thought about doing other stuff?’ because they work with some companies, and they do traditional lights for lantern season in Japan, but they had never done a collaboration with a European designer. So, I suggested we work together, and after a period of time of them thinking about it, we did just that.”

JO: “In the Making, the exhibition we curated at the Design Museum in 2014, where we displayed a series of objects mid-manufacture, started off as an offer for us to do a retrospective. But we didn’t feel like it was the right time, so we decided to do a show about what influences us, which is process and seeing how things are made. Some things are actually more interesting during the manufacturing process, so we did this exhibition of incomplete objects. We both loved those behind-the-scenes bits on kids TV when we were growing up. You couldn’t escape manufacturing in the 1970s, and now, with the commodification of everything, it all arrives in boxes. You’re removed from the joy of making things, and understanding how things are made. It’s the thinking, isn’t it.”

Barber Osgerby, Projects is out now published by Phaidon. A talk by Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby will take place at the V&A on September 18 to mark the book’s launch. Book tickets here.