The photographer and war reporter used cooking as a means of recovering from PTSD, as a beautiful new book details

To many, Lee Miller’s name has been but a footnote in the history of photography and Surrealism, as she never achieved the household-name status her former mentor and lover Man Ray received (thanks in part to their collaborations). A fellow artist, a muse to Jean Cocteau, and a model swept off the streets and onto the cover of Vogue by Mr. Conde Nast himself, to those that know it, Miller’s legacy is entrenched in photography.

Beyond the pioneering Surrealist lens, Miller was also a war correspondent in the 1940s, when she and Life photographer David E. Scherman travelled around Germany, resulting in the now-infamous portrait of a nude Miller perched in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub in Munich. Miller’s own photographs from the period include haunting images of Nazi suicides or a bombed-out London, where she captured a model in front of piles of rubble for the usually glamorous pages of Vogue. In her private life, Miller turned to culinary escapades to cope with the gruesome scenes and experiences.

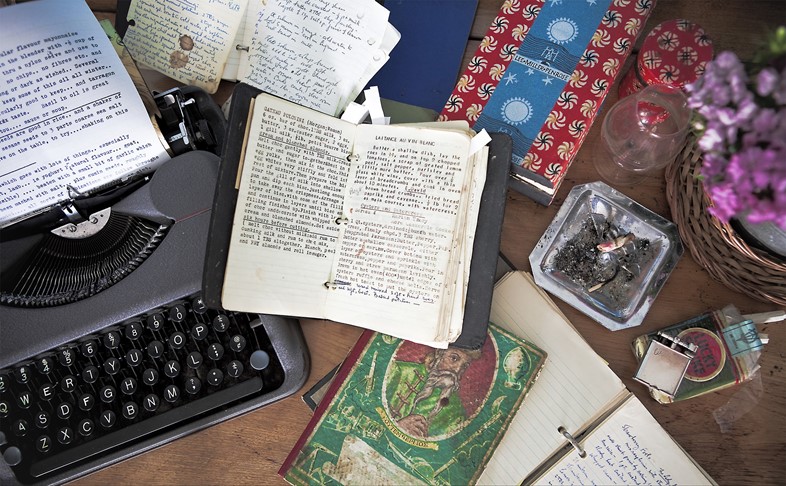

This underdocumented period of her life is brought to light by her granddaughter, Ami Bouhassane, who has painstakingly compiled Miller’s favourite recipes in Lee Miller: A Life with Food, Friends, and Recipes, out this month. “I got tired of the last 20 years of her life being overlooked,” says Bouhassane. “It happens quite a bit when creative women’s stories are told – it’s like after childbirth or around menopause their inventiveness miraculously no longer exists.”

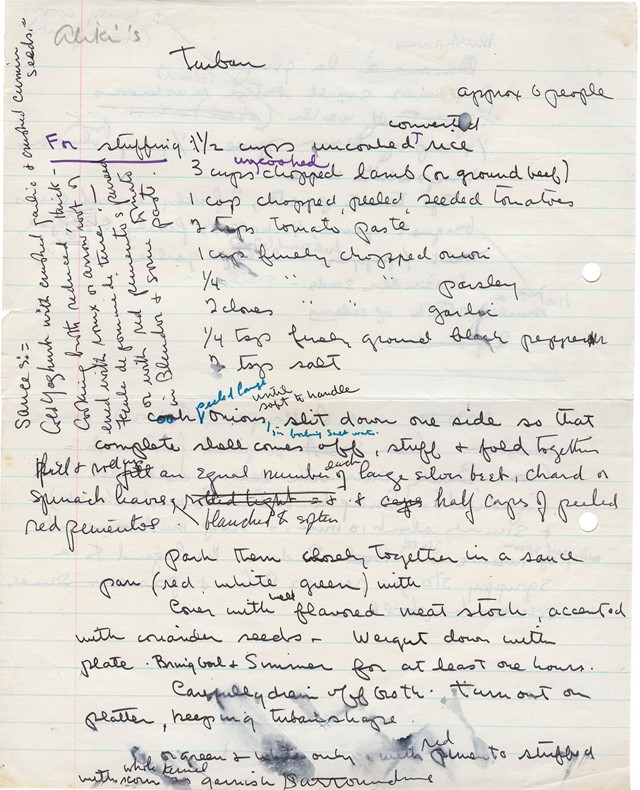

Following her war reportage, Miller suffered from PTSD, and cooking was her escape; she studied at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, and had intended to write a cookbook, having begun a collection of cookbooks so large her husband built a separate room to house them. Touches of Miller’s life as a gourmet chef are documented back in the familiar pages of Vogue; in 1965, Miller (then Mrs Roland Penrose) shared recipes like “Green Chicken for Eight People” in a spread documenting her transition from photographer to chef, the author wryly describing how she cooked “surrounded by Picassos” and the newest kitchen gadgets.

While Miller took life seriously as a gourmand, elements of her surreal past often slipped in: “We had a fair bit of blue spaghetti and very odd coloured scrambled eggs when growing up!” says Bouhassane. Though she was a mere three months of age when her grandmother passed in the late 70s – “we never got to have any kind of conversation that we both understood,” she says, “[though] I know she wrote about me to some of her friends and we have some pictures of me in her arms” – her work as a chef and photographer still permeated Bouhassane’s adolescence thanks to Bouhassane’s father Anthony Penrose, who established the Lee Miller Archive and dedicated his life to sustaining her memory, leaving Bouhassane to follow in his footsteps.

Calling it Miller’s “most extraordinary personal accomplishment,” Bouhassane credits Miller’s cooking as the means with which she combatted serious PTSD – and later, post-natal depression following Anthony’s birth. “Through her material, you can see she has good patches where she’s upbeat and productive, and then there are months and months of struggle or nothing,” says Bouhassane. “But she sticks with her passion, and slowly she emerges.”

More than a traditional cookbook, Lee Miller: A Life with Food, Friends & Recipes is an exploration of this underreported aspect of Miller’s life, and a testament to the healing power of cooking. “It [gave] her a new creative outlet and way to stretch her brain when taking pictures commercially was too hard, and too close to parts of her life she was trying to forget. It was also a way to build bridges with her mother, and enjoy the gift of good food and friends, when you have seen what it is like first hand to have none,” she adds. “It’s extraordinary because it was a long, hard process, and the most complex of all her transformations.”

Lee Miller: A Life with Food, Friends & Recipes is out from November 16, 2017, published by Penrose Film Productions Ltd and Grapefrukt Forlag.