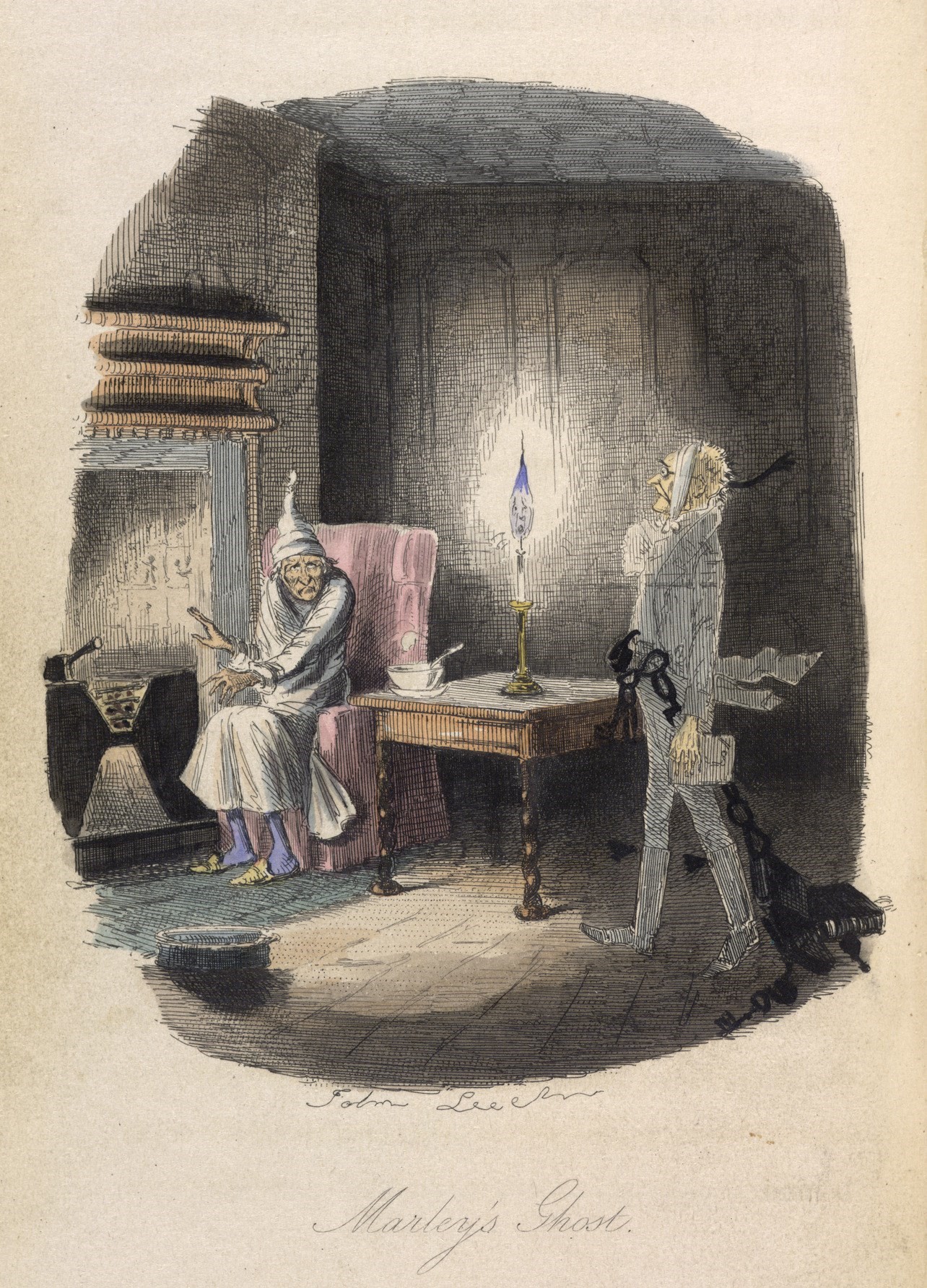

I revisited A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens recently. As I read the narrative of Scrooge and the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future, well known in childhood but long since neglected, I felt overwhelmed by a sense of the uncanny. The characters and the plot were strangely familiar. The familiarity was with the story seen through my eyes as a child, drawn in by the time travel and the plight of crippled Tiny Tim. The strangeness was the gulf I felt between the child and me – though both are me and so – who even am I this year? Like Scrooge, I was confronted with a former self I barely recognised; I was brought a haunting of my own.

I guess that’s partly the point. Dickens draws attention to the particular way that Christmas gathers together past, present and future selves into one crystalline moment. The story exposes a tension between the expectation of repetition, and the guarantee of difference in life. You can’t eat the same turkey dinner twice. In our tour of Scrooge’s Christmases past, Dickens shows us how a joyful, loving youth is gradually transformed into a money-obsessed miser who wishes death upon the poor and who whittles away all kindnesses towards his employee Bob Cratchit. But he is not beyond redemption; Scrooge will not stop becoming different, again. By the end, he is desperate to save Tiny Tim Cratchit from the death sentence of poverty and ultimately becomes a member of their family. Like Scrooge, we are confronted with a Christmas Present produced by decisions made in the past, but its return (again) opens up the possibility of difference (again). It can feel painful, exciting, redemptive, even boring, but the future will be transformed by our actions now – and there lies the beginning of hope.

To set the right conditions for the return of Christmas, we practice a form of pagan, everyday magic. We gather greenery and silver baubles to decorate the insides of houses, kiss under poison berries, mix hot and potent spiced drinks to fire up our spirits and chant along to songs played over and over again. We repeat the preparation of dishes and sometimes alter them to please our evolving tastes.

Dickens attends fastidiously to the earthly rituals that made Christmas in the 1840s. What I notice in A Christmas Carol that I missed as a child is the food, as in the vivid depiction of Christmas Present:

“Heaped up on the floor, to form a kind of throne, were turkeys, geese, game, poultry, brawn, great joints of meat, sucking-pigs, long wreaths of sausages, mince-pies, plum-puddings, barrels of oysters, red-hot chestnuts, cherry-cheeked apples, juicy oranges, luscious pears, immense twelfth-cakes, and seething bowls of punch, that made the chamber dim with their delicious steam.”

A symptom of Scrooge's lack of goodness is his rejection of gustatory pleasure, expressed concisely by a bowl of gruel left uneaten in his grim apartment. The first deed of Scrooge’s spiritual awakening takes the form of a fattened prize turkey sent to the Cratchits in a great hurry. The comically large bird, bigger than Tiny Tim and requiring a cab to transport it, marks the beginning of Scrooge’s redemptive participation in Christmas.

Like Dickens’ characters, I, too, orient my participation in Christmas around food. Through the repetition of annual food rituals I experience an encounter with myself (usually less extreme than Scrooge’s haunting) and I feel the difference each time they are repeated. Some are more traditional than others. Here are three:

Christmas Eve, McDonalds with my dad

I cannot remember when this began, but it is the only aspect of Christmas eating that was never intended by my mother. It arose a decade ago or more when my father was still working and finished at lunchtime on Christmas Eve, but had somehow left himself a fairly substantial amount of present-buying before the shops closed 3 hours later. He was an NHS dentist in Ipswich. Christmas shopping with him was a kind of glory lap, where someone in every shop wanted to thank him for this or that treatment or advice (he had around 10, 000 patients on his books). He often panicked because he couldn’t remember the names of patients who stopped him in the street. In the morning when he was at work I would reacquaint myself with the cut-throughs and pedestrian zones of Ipswich carrying out a ‘recce’, ready for a rapid dash round when he finished work. Sometimes one of my brothers came too. There would come a point in the afternoon when we would all stare hard at some too-extravagant present that dad wanted to buy mum, but wasn’t sure about. I was there to advise. While dad is reliably impulsive, my mother is reliably horrified by excess. At some point I convinced my dad to take me to McDonalds to reward me for such committed Christmas labour. He’ll have expressed a loyal degree of guilt at losing his appetite for my mother’s cooking that night, but, I’d have known when I asked that dad likes the faint disobedience of a secret burger that we eventually ‘fess up.

McDonalds in Ipswich on Christmas Eve is bananas. Everyone is there. Typically there are teenagers in tracksuits and new trainers hanging out in the foyer bit just inside the door, then long queues and the brightly coloured booths are rammed with families, children and shopping bags upstairs. I always have a quarter pounder with cheese meal and a coke and dad has a big mac meal. He actually prefers Burger King, but I prefer McDonalds, which is pride of place on the high street, just along from the Great White Horse Hotel (which appears in The Pickwick Papers after Dickens stayed there – and is now a Starbucks).

My dad retired a couple of years ago and now has far more time to do his Christmas shopping. In fact, he hasn’t really needed to do our traditional supermarket sweep of Ipswich recently. Would we lose our annual moment of solidarity and sense of having saved Christmas by a hair’s breadth? My dad’s life has lost the time-pressed urgency of working round the clock; he has the time to shop and carefully consider his gifts for my mother. I worry that perhaps he won’t need me as his Christmas accomplice now? We have both grown up.

Somehow, though, each year since he stopped working, my dad has thought of a few forgotten presents that he just might need my assistance with. We have bundled into the car, perhaps a little knowingly, to drive into town. We don’t rush quite so frantically and there’s less to do: we don’t really need to go. What sprung up without thought to solve a problem has entered the annals of tradition; we have acknowledged the burgers and fries as sacred ritual. They have a higher purpose.

3am Christmas Morning, Tangerine

I never eat the tangerine at the end of my Christmas stocking (which is more of a long sock), but I feel for it first of all when I wake up to investigate matters. It is the least exciting but most important item in the stocking. The orange-scented oils in its skin as I drag it out from the toe in the very early morning is the first smell of Christmas day. Perhaps I do not eat it because it would feel like eating a rare and precious form of magic folded into an object. Contained in the tangerine are all of my hopes for Christmas before they have unravelled. The promising mystery I obsess over of wrapped objects under the tree and the anticipation of reactions to the mysteries I have hidden beneath cheap glittery paper, poorly wrapped. Whatever, I just don’t really regard the tangerine as food, more as emblem. Peeling it would reveal too much at 3am and by the evening when I return to my room, I already know everything. I find it softened and dried out or a little mouldy months later, its ghostly but evocative perfume reminding me suddenly and intensely of the spell it cast, now all spent.

11am Christmas day, Milk with Onion, Bay Leaf, Cloves and Peppercorns

I have never drunk plain milk from a glass. As a child I hated the taste, which I found deeply unsettling. I still do. So in-between things and as pale in flavour as in colour. Yet distinct, too. Uncannily sweet but unsweetened. Almost translucent. Watery but coating the palate. Suddenly off and reeking of rot. Poof! Altogether too indistinct. It was definitely the liminality of milk that spooked me. Where the flavour becomes defined, I love it. Milkshake and hot chocolate are firm favourites, as is macaroni cheese. But bread sauce, made exclusively at Christmas in my family, filled me with disgust. I had it once early on and was almost immediately sick. It seemed like milk tainted with the spectres of other flavours. Yes tainted, but not enough and what an inexplicably revolting texture.

Nonetheless, for at least fifteen years I have been my mother’s sauce cook on Christmas day. I make bread sauce, cranberry sauce and brandy butter. I take pride in these tasks and fish for praise for them too often. Until recent Christmases, I can’t remember when, I made the sauce following the instructions in Delia’s Christmas book to the letter, and did not eat it. I held my breath when it passed under my nose at the table. I made faces at it. But when did I change? Now I love it. I cannot trace the genesis of the change. But perhaps it was when I began liking eggs and mayonnaise in my early 20s. To me this makes sense. Eggs and mayonnaise are similarly in-between to my palate and perhaps I got over their hovering mildness when I became a little firmer about who I was.

Now there is little finer to me than halving a small brown onion, peeling it, and sticking the cut side with cloves, and dropping it into a saucepan of creamy milk with a bay leaf and some black peppercorns and setting it on the heat. Because milk boils over so quickly on account of the sugars in it I must stand by the pan to keep watch as it heats and so inevitably inhale the dreamy infusion of the steaming milk and the flavourings. When it has almost boiled I set it aside for a few hours to take on more flavour while we make the rest of the preparation for the feast and around 30 minutes before eating, I add soft white breadcrumbs and seasoning and stir slowly on a low heat the bread expands and thickens the sauce. At the last minute I stir in some yellow butter and remove the onion and bay and tip the sauce into a bowl with a silver spoon.

...

As I roll this year’s tangerine around in my palm, releasing little bursts of orange scent and anointing myself with Christmas cheer, I think of Scrooge’s revelation as he springs from his bed with the realisation that he has the power to change his life. What the story taught me a an adult that I was not ready to understand as a child is that every repetition of Christmas, even as it feels utterly familiar, reveals the differences that we bring about individually and collectively, every year. Therein lies the power, the hope and the glory vested in us, by us.

“The bed was his own, the room was his own. Best and happiest of all, the Time before him was his own, to make amends in!

‘I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future!’ Scrooge repeated, as he scrambled out of bed.

‘I am as light as a feather, I am as happy as an angel, I am as merry as a schoolboy. I am as giddy as a drunken man. A merry Christmas to everybody! A happy New Year to all the world. Hallo here! Whoop! Hallo!’”