“There is no substitute for gold,” Derek Jarman once wrote – and from Monroe’s glittering halterneck to Linklater’s favourite evening light, we can’t help but agree

Winter sees us creating light and sparkle out of the darkness, using decorative lights and baubles as a defence against the gloom of winter. There is value in gold, beyond the element’s rarity and its price at global markets, and it comes from our attitude towards it and its lustre. “There is no substitute for gold,” Derek Jarman wrote in Chroma: A Book of Colour, his exploration of colours and artistic process. “It cannot be invented in the chemist’s shop like the colours.” It might be the purest explanation for why we prize gold above all else: gold standard, gold mines, streets paved with gold. “Gold is the aim of the pursuit, fired by learning rather than greed,” Jarman continues. Both the colour and the material are prized, and yet their use in culture is not necessarily a straightforward question of value and lustre and pomp. After all, it’s never just about the price of gold. There are complex ideas of memory and nostalgia and glamour all bound up in the hue, and those can’t easily be reduced to a number on a spreadsheet.

Art

In Chroma, Jarman describes Annunciation by Simone Martini as “the most golden painting”, a wooden triptych painted with tempera and gold leaf. It depicts the archangel Gabriel announcing to Mary that she will soon give birth to Jesus, and was painted originally for the Siena Cathedral. It now resides at Florence’s Uffizi Gallery. As the author points out, only a small amount of blue lapis features in the entire painting, on the robes of the Virgin herself.

Works from Gustav Klimt’s golden phase, where the Austrian artist combined oil paint and gold leaf, became some of his best known, and in 2006 Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I became the then-most expensive painting ever sold, at the sum of $135 million. But the relationship between gold in art and financial value is not always so direct. In 1959 Yves Klein began selling chunks of the Zone de Sensibilité Picturale Immatérielle, or the Immaterial Zone, in an artwork of the same name. Klein would exchange empty space for a cheque for an amount of gold from the buyer, which he would then throw into the River Seine while the buyer burned the cheque symbolically. This playful approach to something that underlies much of our social systems has been expanded upon by artists since. The Italian avant garde artist Piero Manzoni started selling cans marked ‘Artist’s Shit’ in 1961, with their price based on the price of gold at the time. 90 were created at the time, shortly before the artist’s death in 1963. But it has never been established if the cans actually do contain what they say on the tin – opening them to find out would render the artwork worthless.

Film

Photographers and directors will push and pull their team’s schedules to chase the elusive golden hour – the brief window of time just after dawn and before dusk when light is red and soft. This light, fleeting as it may be, flatters and also creates a certain quality of atmosphere that you’ll recognise from the work of directors such as Richard Linklater and Terrence Malick. In both Badlands and Days of Heaven, for instance, ordinary rural tableaus become infused with golden light, a painterly haze that tells a story in and of itself. The effect is replicated in Spring Breakers, and used as a narrative device to lend the aura of memory and nostalgia to the protagonists’ lives, as in the scene in which James Franco plays Everytime by Britney Spears on the grand piano by the ocean.

Fashion

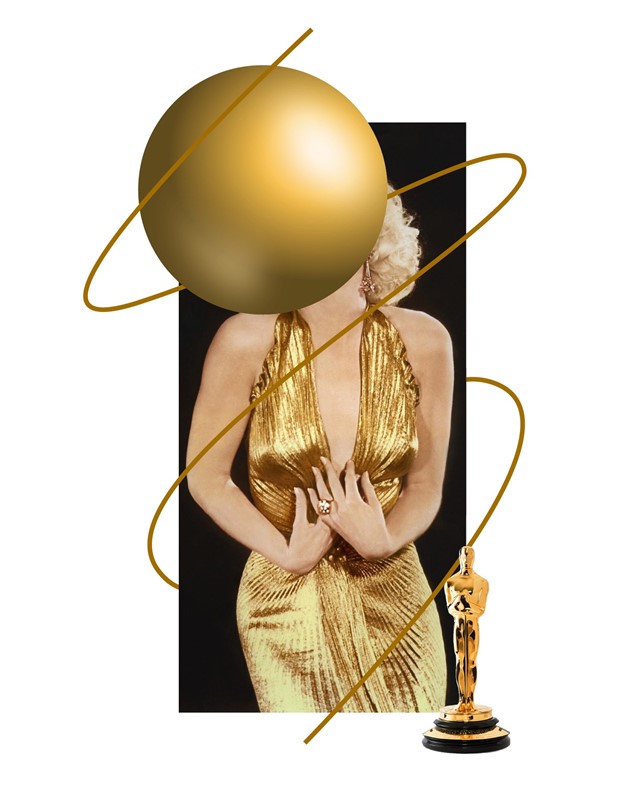

In cinema and in fashion, gold treads a similarly evasive terrain. It’s not only eye-catching, but also special, and can often contain a nod to the glamorous history of Hollywood. Check Marilyn Monroe’s famous gold lame halterneck dress featured in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes – it could probably be in the encyclopaedia entry for the colour, given how iconic it has become.

So it can be difficult for a gold dress to escape the context in which it occurs. Yet worn correctly, the colour can still make for an unforgettable style moment, particularly if she who wears it is at the top of her game at the time. For evidence, see the stars who have chosen to wear gold to the Oscars, in a way mimicking the gold statuettes handed out – at least for the tabloid headline-writers the following morning. Meryl Streep wore a gold draped lamé dress by Lanvin to collect a Best Actress award for The Iron Lady in 2012. Nicole Kidman wore a shimmering gold Dior dress to the Oscars in 2000 – the last she would attend with Tom Cruise. But long before either of those made the plunge, Farrah Fawcett went for a slinky gold chainmail dress by Stephen Burrows for the 1978 awards, the epitome of 1970s glam and a disco style moment for the ages. She may have turned heads on the night, but Fawcett also created a benchmark – a gold standard, if you will – for how to wear this unique colour.