There is nothing left where the first block of the iconic housing estate Robin Hood Gardens once stood. The second block opposite is still awaiting the bulldozers. After multiple attempts to save the building and have it listed as an important structure in the city, there is only a fragment of it left that is now sitting in the light of the lagoon in Venice – ahead of its total destruction, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London acquired a segment of the building’s exterior which is now on display at the Venice Architecture Biennale. The reassembled fragments have been positioned to look like its original façade outside on the water and will allow people the ability to walk up the stairs and experience the building as if it was still standing. It is the key feature of the exhibition Robin Hood Gardens: A Ruin in Reverse, a collaboration between the Venice Architecture Biennale and the Victoria and Albert Museum, curated by Dr Christopher Turner and Dr Olivia Horsfall Turner.

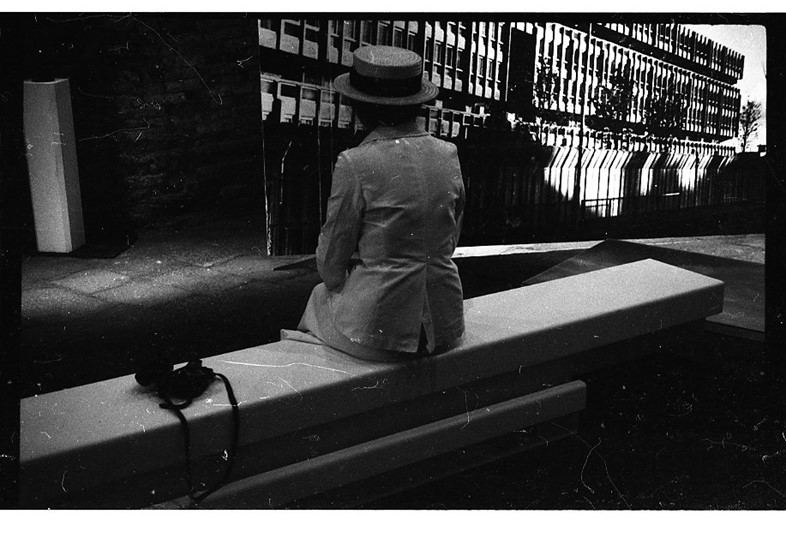

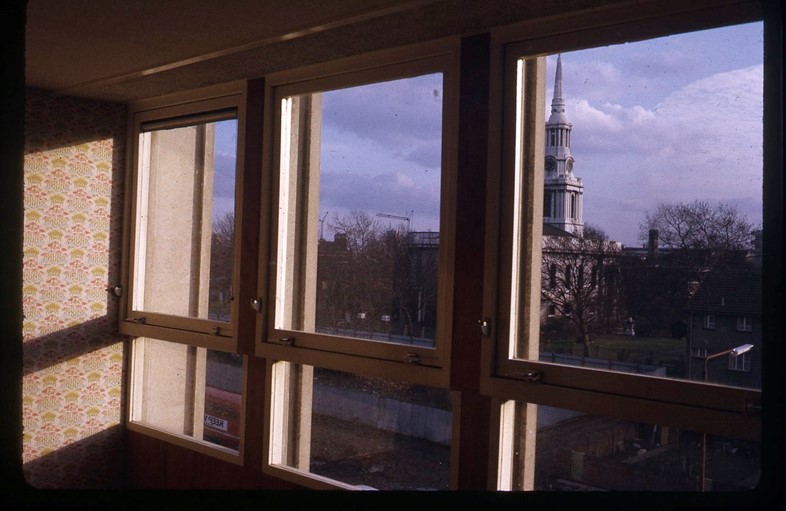

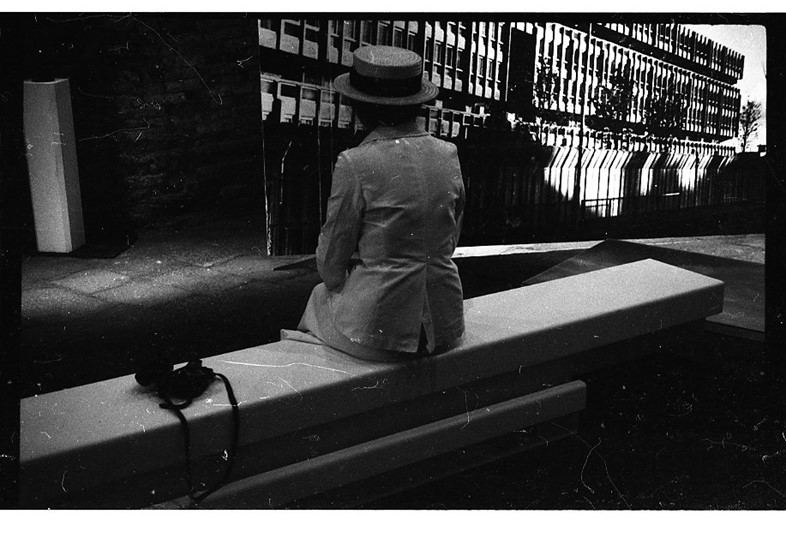

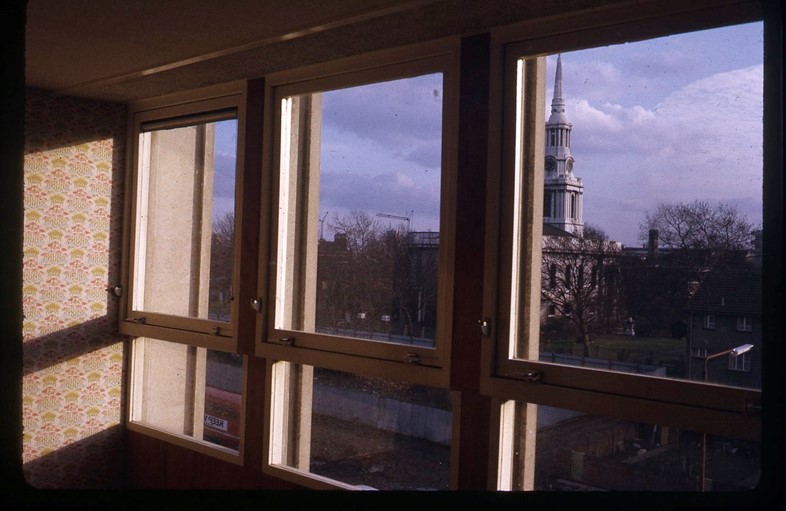

Robin Hood Gardens was completed in 1972 and set a precedent in the form and quality of public housing in London. It was the only social housing project to be built by British architects and Alison and Peter Smithson and features their trademark ‘streets in the sky’ walkways which can be climbed up in the exhibitions’ display. Like many post-war estates, Robin Hood Gardens has been demolished before its time. It was hundreds of families’ homes over the last 40 years, and that is what the archive images from the Smithson Family Collection portray. They capture the architect’s original desire for the estate to be a place of hope in what once was a lush green part of London. Documentary filmmaker Joe Gilbert has been filming Robin Hood Gardens for the last five years and says “it is a relic of an era that simply doesn’t exist anymore, and is representative of a time of post-war optimism that put people before profits”.

“We think that the peculiarity of seeing a building that should be in London will prompt people to ask questions about how it came to be in Venice, and through that they will think about the financial, social and economic contexts that surround the demolition of Robin Hood Gardens,” comment the curators. “Having a diverse community is an essential part of building a strong society. We want visitors to the Pavilion of Applied Arts at La Biennale di Venezia to revisit the Smithsons’ vision for a new way of living, and be inspired to think as boldly as they did about the right of everyone in society to enjoy living in the city. Social housing is one of the most pressing issues in metropolitan centres across the world.”

When it was originally in the process of being built in the late 60s and 70s, the Smithsons clouded the view of the construction site with a billboard of what it was to be, writing that “a building under assembly is a ruin in reverse”. Liza Fior from Muf, the architecture practice that first suggested the V&A acquire parts of the estate, says she hopes that “unpacking the history of Robin Hood Gardens can protect other housing which is currently under threat”. The exhibition explores the entirety of this infamous estate through both the physical structure, formed from its concrete exterior, and the immaterial, in Korean artist Do Ho Suh’s installation, commissioned by the V&A to create an immersive experience of the building. Do Ho Suh’s work inside the Pavilion of Applied Arts maps a memory of the building through drone footage, time-lapse photography and 3D scans of the building, in order to accurately document the lives that once lived in Robin Hood Gardens.

Robin Hood Gardens: A Ruin in Reverse will be presented by the Victoria and Albert Museum and La Biennale di Venezia at the Pavilion of Applied Arts from May 26 to November 25, 2018.