The Fondation Maeght is perched on the top of a hill in a thickly wooded forest outside the medieval Provençal town of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, and unless you’re one of the lucky few on holiday at one of the luxury hotels dotted nearby, visiting involves a bus ride from the tourist-packed towns of Nice, Cannes or Antibes. Disembarking and walking up the hill to its imposing gates feels like a pilgrimage. On a summer’s day, heat shimmers on the asphalt, and the striking geometric lines and curves of its exterior come together like a mirage – a shrine to Modernism hidden behind a tangled cluster of cypress trees.

It was here, in June 1964, that the Parisian art dealer and staunch supporter of the French avant-garde Aimé Maeght and his wife Marguerite opened their tribute to the greatest creative figures of their day. Inspired by Joan Miró’s studio in Palma, Mallorca, they hired the Catalan architect Josep-Lluis Sert to work on the building in collaboration with figures from their glittering social circle: Miró, unsurprisingly, but also Georges Braque, Alexander Calder and Alberto Giacometti.

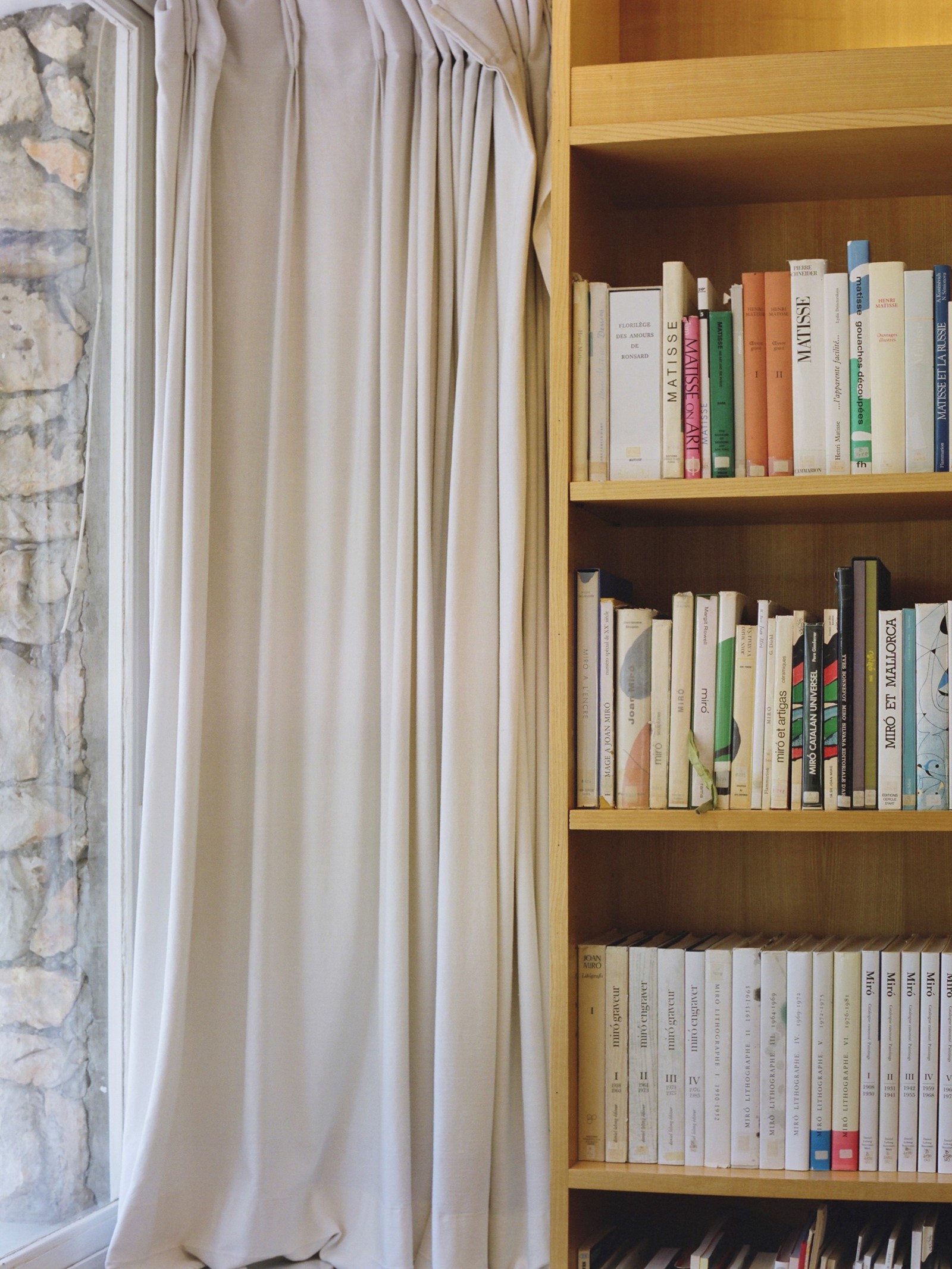

The end product was a seamless blend of art, architecture and landscaping: Miró conceived a labyrinth that contains over 250 individual works, a meditation on his lifelong obsession with the mythological minotaur of Ancient Greece; Braque and artist Raoul Ubac created stained-glass windows for the chapel that paid tribute to the Maeghts’ deceased son, Bernard. The entire complex was carefully designed to exist in harmony with its surroundings – in Sert’s words, an attempt to “install a museum inside Nature” – and its strange mass of curving roofs and jutting terraces lends it a distinct sense of the uncanny.

Against the congested autoroutes and urban centres of the gateway cities nearby, the building feels shrouded in a hushed, orphic aura – that “weave of space and time” cited by Walter Benjamin that gives the authentic artwork its own strange magic in the age of modernity where any picture can be endlessly reproduced. For Benjamin, one of the elements contributing to the artwork’s authenticity is a sense of ritual: as we process through the darkly lit exhibition space and look at placards that explain the object’s meaning, the experience leaves us convinced that what we are seeing is somehow important.

How much of this experience – the weighty sense of cultural significance, the aura of dormant creativity – relates to a work of architecture? Am I just imagining the gravity that seems to radiate from this building: am I just conditioned to feel like this, thanks to everything I’ve read about this place, and the sheer effort it takes just to get here?

After all, the Fondation Maeght is far from a relic: it’s a living, breathing museum, that continues to support creatives pushing against the boundaries of artistic conventions today. The current exhibition looks at Lee Bae, an ambitious Korean artist whose work responds to the legacy of the recently fashionable Dansaekhwa movement. It’s a curatorial choice that makes clear the current owners of the Maeght – a board that includes descendants of the founders – have a finger to the wind in the contemporary art world.

So too is their willingness to invite Louis Vuitton to stage their cruise collection at the Maeght testament to their open-mindedness. Many art institutions would turn their nose up at a fashion show being held on their premises, but the meticulously researched designs of Nicolas Ghesquière, informed by everything from French medieval history to sci-fi cinema, are a perfect fit for this offbeat architectural anomaly.

Perhaps mythologising a place like the Maeght does it a disservice. Yes, it was conceived at a particular moment in time, and much of its appeal to tourists lies in that post-war artistic culture. But if we romanticise it so that it never leaves that moment, we deny it the chance to enter into dialogue with artists now: it’s reduced to something quaint, an antique. There’s no reason why an institution like the Maeght should be stuck in the past – and for those willing to see the foundation with fresh eyes, witnessing how Ghesquière interprets and responds to this artistic heritage in his latest collection isn't a bad place to start.