The John Schlesinger-directed movie was the only X-rated film to win Best Picture at the Oscars – and 50 years on, it’s still making waves

As a timely riposte to the all-American heroics of Clint Eastwood and John Wayne, Midnight Cowboy explores men falling between the cracks of Nixon’s America. The first queer film to win Best Picture at the Oscars, and the only X-rated film to do so, it’s an unsentimental take on poverty, masculinity, and identity. It merits revisiting nearly half a century on, and is now available in a digitally restored version, thanks to the Criterion Collection.

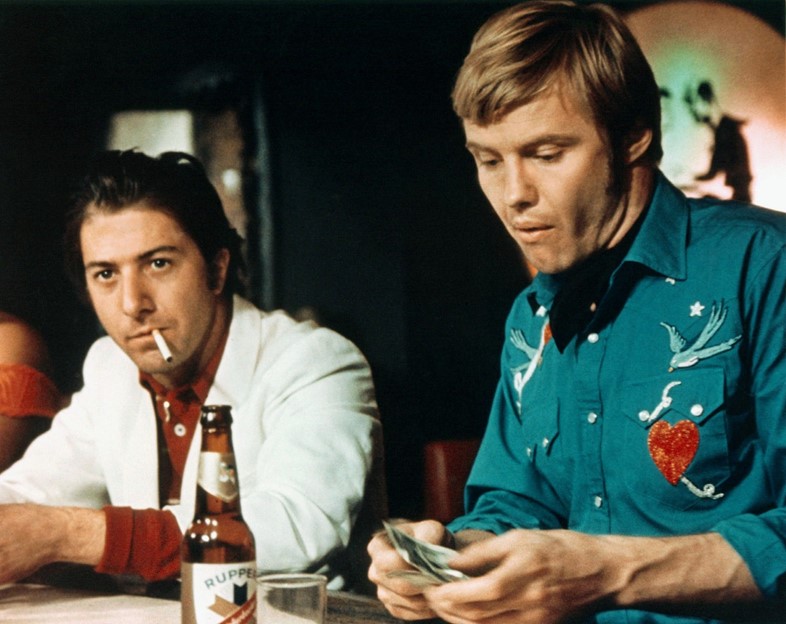

Doe-eyed hunk Joe (Jon Voight) abandons life as a dishwasher for the streets of NYC, resolved to make it as a male prostitute, decked in the cowboy attire of a John Wayne wannabe. He runs into motor-mouth, cigarette-flicking Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), promising to act as pimp while they fend off poverty and approach something like friendship. Their fragile masculinity and identities hinder their luck, but win our sympathies, as director John Schlesinger explores how to make a man in a society ruled by a constrictive masculinity. The ensuing decade of subtler, more ambiguous antiheroes on screen (Taxi Driver, Chinatown, and Saturday Night Fever), is largely indebted to the film’s frank sexuality and brutality.

While Midnight Cowboy shirks the romantic edge implied by its title, Joe’s viewpoint of masculinity has been shaped by his diet of by-the-numbers Westerns. We first see this chasm between his naive identity, and the brutal realities of the world, when he realises the true symbolism of his cowboy jacket – as a calling-card for young gay men. Desperate and conflicted, Joe flits between acts of brutality and sweetness, existing in the void between who he is and what he wants to become.

Leered at by women in cat-eye sunglasses, propositioned by men, condemned by a preacher – Joe finds the big city is no more accommodating than the violent small-mindedness of his hometown. Raped and beaten by local townsfolk, Joe has become desperate to assert his worth, tragically confessing to Rizzo: “The only thing I ever been good for is loving.” Shifting into the skin of a cowboy, and seeing it as his manifest destiny to go east, Joe is still unable to assert his own sense of law and order. He’s a man out of time and place, neither Beatnik nor Bolshevik, in a society where the lonely, the abused, and the queer must fight to assert their identity.

There’s a latent homoerotic touch to Joe’s and Rizzo’s friendship, made real by its petty bickering and staccato displays of affection. Schlesinger finds a sweet pathos in the way men prop up one another’s manufactured sense of selves, alloying their fantasies in exchange for friendship. Small moments show this, such as when Joe threatens, “I’m a dangerous killer”, and Rizzo, with an eyebrow raise and slight monotone, dutifully replies, “I’m impressed. You’re a killer”. These men are fragile and shifting in their skins (quite literally in Rizzo’s case), neither cowboys nor hustlers, winning our sympathies through their vulnerability, not their John Wayne-grit or brawn. When Joe obliquely refers to his sexual abuse, it underlines how this platonic friendship is the first true one he’s had, devoid of manipulation and mistrust.

Joe’s and Rizzo’s poverty makes them men apart – they’re isolated in a decayed squat, walking amid a carnival of billboards speaking loudly to a different America (Schlesinger pans to billboards saying “If you don’t have an oil well… get one,” and “Steak for everybody – every lunch and dinner.”) A wannabe pimp, and a would-be cowboy, they inherit archetypes which fit poorly, like the over-large sheepskin coat Rizzo swipes for Joe. Schlesinger wrings the grim reality of their living situation for a kind of deadpan comedy, mocking the mania of New York around them: ad jingles serve only as something to dance along to, to stay warm, and a dead-eyed street photographer snaps Joe’s profile, capitalising on his poverty for the sake of cool. At least they have made an authentic home together. In a film littered with iconic moments – such as Hoffman’s improvised “I’m walking here!” outburst – none draws our sympathies like the end scene, with Rizzo and Joe on the cusp of a new life together.

Hollywood commonly shies away from a feel-bad ending, but Midnight Cowboy allows it, wanting to stay true to the banal realities of American life for men like these. The ending doesn’t reward Joe’s naivety. Succumbing to a fever, Rizzo dies, pallid and slack-jawed on their night bus to Florida, as Joe allows his first display of affection; a taut arm around the shoulder of his friend’s corpse, staring out the preying eyes of others. He’s dressed in the bright palm-tree shirt Joe had bought for him, dreaming of a hustler-free existence in Florida. In one fell swoop, Schlesinger kills the American dream, leaving it stranded on their Greyhound bus. All that’s left is the men’s friendship, Florida’s blue skies, and the palm trees rushing past the windows.

Midnight Cowboy is available now, digitally restored by Criterion Collection.