“She is brave, she makes us think, she demands to be read in full,” writes Lucy Kumara Moore of the American academic, in the second instalment of SEXNESS

SEXNESS is a new monthly column exploring the shape of 21st-century desire from Lucy Kumara Moore, director of Claire de Rouen bookshop. A drive from the deep, a contested ground, a spur to our true identity, desire is manifold. Without aiming to be comprehensive, SEXNESS interweaves conversations with friends and personal perspective, to generate a PLEASURE-POSITIVE transmission from the cultural now.

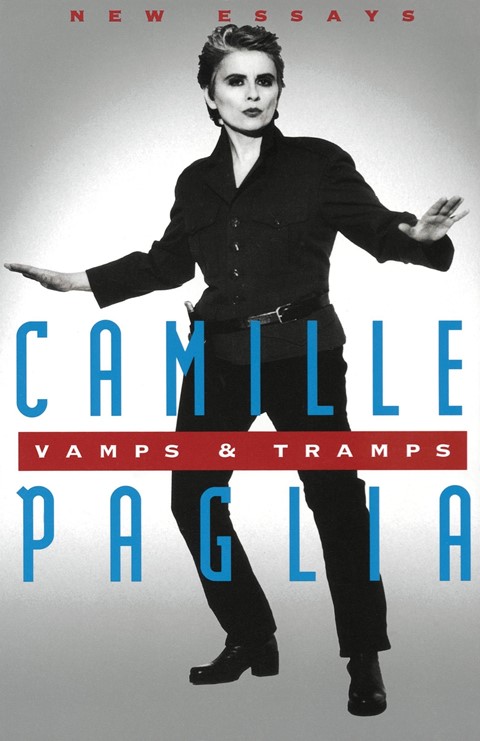

For a long time, I mistakenly thought the social critic and academic Camille Paglia was French, perhaps because of her first name, but more likely because so many of the prominent figures in the library of my mind with an intellect akin to hers – daring, full of elan (to the max!), incisive, subversive – and who address similar subjects – gender, societal constraint, desire – are French. I grew up on Simone de Beauvoir, Anaïs Nin, Jean-Luc Godard, Marcel Duchamp and Georges Bataille, and more recently filmmaker Catherine Breillat, writer Virginie Despentes, and my half-French friend, the artist Navine G. Khan-Dossos, have made a strong impression. But Paglia is American, and from the cover of her 1994 book Vamps & Tramps (above), which pays homage to New York artist Robert Longo’s series of drawings Men and the Cities, I should have known. (Paglia also comments regularly on the socio-political landscape of contemporary America, but my first encounter with her came via her book on the Pagan undercurrents of Western culture, Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson.)

In fact, although complementary about de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, Paglia has bemoaned the strong influence of many of the recent major French thinkers. Of philosopher Michel Foucault’s work, for example, she states: “The most serious flaw of Foucault’s system is in the area of sex. I view his hurried, compulsive writing as a massive rationalist defense-formation to avoid thinking about a) woman, b) nature, c) emotion, and d) the sexual body.” Rumour has it she’s also called him “a bastard”! This kind of hardcore oppositional statement is typical. Paglia is fearless, extreme, unapologetic. She talks of Emily Brontë’s novel Wuthering Heights as a study in sadomasochism, of the nuclear family as “an artificial and oppressive construction”, of the importance of the elitist criteria of excellence and distinction for maintaining artistic standards – all propositions that diverge wildly from the norm. In 2019, some of what she says can feel old fashioned, offensive even, especially when read out of context. And yet, she’s been circling my thoughts recently, like an auto-imagined hawk on the look-out for a lapse in my focus or conviction. I’ve been wondering why... I’ve been feeling I should give it some attention. When I saw a photograph of Paglia draining a glass of beer by German-Korean artist Heji Shin, at Paris’ FIAC art fair last October, I took it as a sign. And so, for this second outing of SEXNESS, I decided to write about why I love Camille Paglia, and about why I think we need her, right now...

1. Her writing is scintillating and alluring and funny – we need more commentators on gender and desire who keep a keen eye on their style. I especially love these missives from her satirical advice column for Spy magazine:

“Sex is the biggest electric company of them all. It shocks, short-circuits, overloads, and generally fries the brains.”

On Madonna’s book Sex “wrapped in Warhol silver like an interstellar candy bar, [Sex] promises a flight of imagination but delivers a very bumpy ride”.

Paglia knows sex won’t go away. Her feminism grapples with the forces of desire.

2. She’s an individualist feminist. What’s that? At a time when new feminist activism has so much potential to push things forward, being aware of feminism’s history is crucial. Individualist feminism focuses on equal rights and on removing class and gender oppression via law. It calls for women to take responsibility for their own lives, and holds that a woman’s sexual choices should be made by her and her alone (I’m paraphrasing Wikipedia here). All of this is distinct from gender feminism, for example, which asserts that gender is performative, socially-induced and separate from biological sex. Being aware of the different ways in which feminist discussion can be framed, the different emphases it might choose to make, especially in relation to sexuality and desire, is deeply important at a time when so much constructive energy is being focused on the shifting of paradigms.

3. Paglia once shared grapes and wine with Lauren Hutton while talking about the importance of “keeping men hot” and “the glory of male lust” in a black Gaultier corset dress. In 1992, Luca Babini’s film Sex War saw the two discuss their love of the distinct qualities of male desire and male sexuality. Paglia’s thinking, which foregrounds women’s equality, respect and pleasure, suggests the mutuality of desire is central to any debate.

4. Paglia is anything but politically correct – she is brave, she makes us think, she demands to be read in full – only then can we accurately glean her position; she is not Twitter-friendly. Setting out the terms of her intellectual career long before the advent of the internet, Paglia has complex, layered, inventive ideas that can’t be articulated in soundbites. She asks a lot of her reader: she asks for our time and patience.

Read her now on Trump and Hillary Clinton, on Bradley Cooper’s remake of A Star is Born and on Barbra Streisand and Nefertiti. Camille Paglia is like Marmite. And I like her.