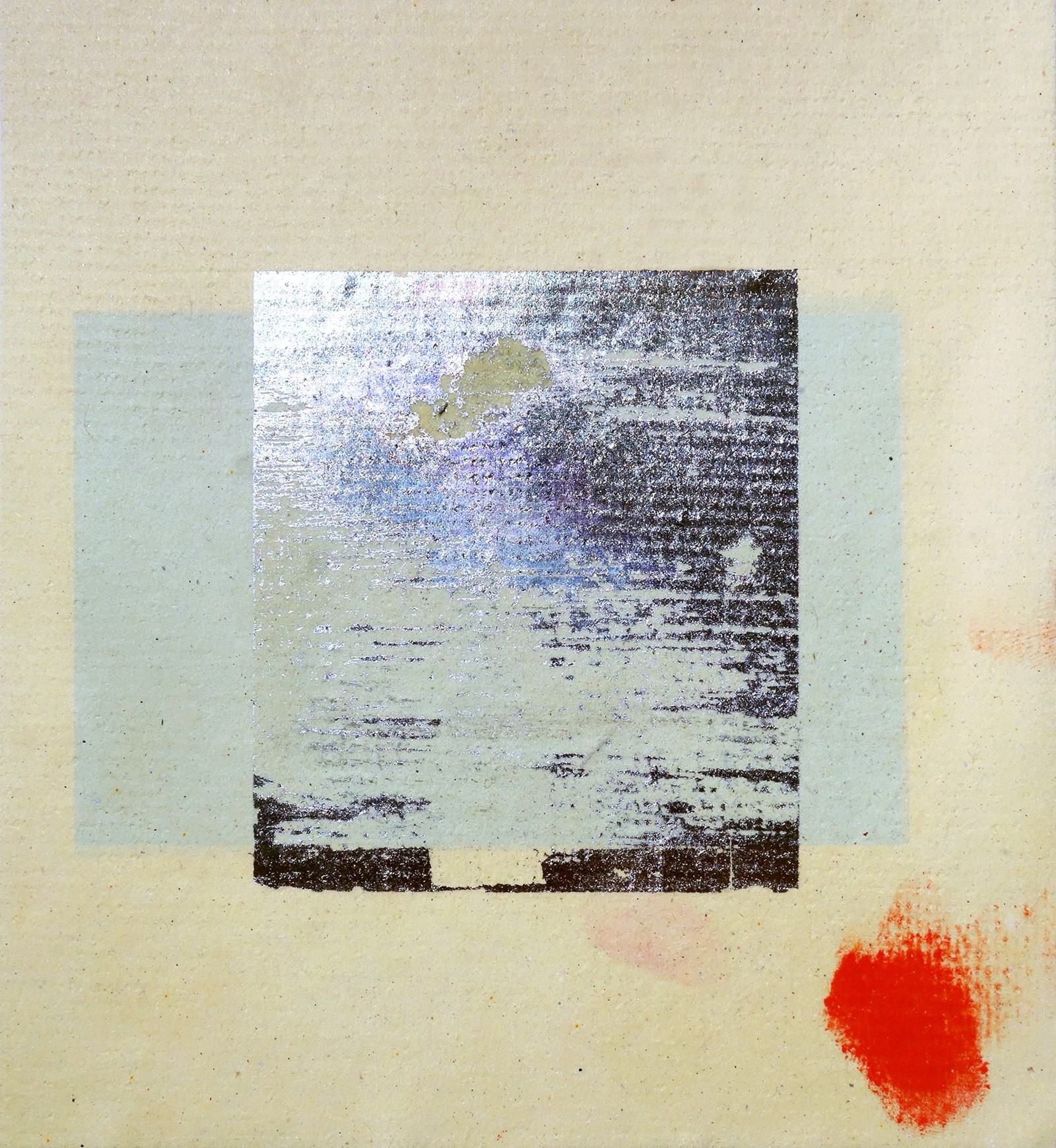

For the latest issue of AnOther Magazine, we asked Björk to compile an anthology of texts that have inspired her. Drawing on the research undertaken for her upcoming show at The Shed, Björk’s Cornucopia, which premiers this month, the Icelandic artist gathers together the work of some of the most important post-feminist thinkers of the age and puts her own determinedly maverick and truthful stamp on the anthology. Björk has compiled an agenda for hope and reconnection, accompanied here by a dedicated series of imagery created by artist Wanda Orme.

A majestic and philosophical homage to the wild, windswept Cairngorm Mountains in the eastern Highlands of Scotland, Nan Shepherd’s lyrical pilgrimage The Living Mountain is less about reaching a summit than melting into the extraordinary sensations of the natural world on her journey. Into the air and light, the mists, silences and secrets of an ultimately unknowable, occasionally terrifying “mass of granite”.

The plateau

Summer on the high plateau can be delectable as honey; it can also be a roaring scourge. To those who love the place, both are good, since both are part of its essential nature. And it is to know its essential nature that I am seeking here. To know, that is, with the knowledge that is a process of living. This is not done easily nor in an hour. It is a tale too slow for the impatience of our age, not of immediate enough import for its desperate problems. Yet it has its own rare value. It is, for one thing, a corrective of glib assessment: one never quite knows the mountain, nor oneself in relation to it. However often I walk on them, these hills hold astonishment for me. There is no getting accustomed to them.

The Cairngorm Mountains are a mass of granite thrust up through the schists and gneiss that form the lower surrounding hills, planed down by the ice cap, and split, shattered and scooped by frost, glaciers and the strength of running water. Their physiognomy is in the geography books – so many square miles of area, so many lochs, so many summits of over 4,000 feet – but this is a pallid simulacrum of their reality, which, like every reality that matters ultimately to human beings, is a reality of the mind.

The plateau is the true summit of these mountains; they must be seen as a single mountain, and the individual tops, Ben MacDhui, Braeriach and the rest, though sundered from one another by fissures and deep descents, are no more than eddies on the plateau surface. One does not look upwards to spectacular peaks, but downwards from the peaks to the spectacular chasms. The plateau itself is not spectacular. It is bare and very stony, and since there is nothing higher than itself (except for the tip of Ben Nevis) nearer than Norway, it is savaged by the wind. Snow covers it for half the year and sometimes, for as long as a month at a time, it is in cloud. Its growth is moss and lichen and sedge, and in June the clumps of Silence – moss campion – flower in brilliant pink. Dotterel and ptarmigan nest upon it, and springs ooze from its rock. By continental measurement its height is nothing much – around 4,000 feet – but for anisland it is well enough, and if the winds have unhindered range, so has the eye. It is island weather too, with no continent to steady it, and the place has as many aspects as there are gradations in the light.

Light in Scotland has a quality I have not met elsewhere. It is luminous without being fierce, penetrating to immense distances with an effortless intensity. So on a clear day one looks without any sense of strain from Morven in Caithness to the Lammermuirs, and out past Ben Nevis to Morar. At midsummer, I have had to be persuaded I was not seeing further even than that. I could have sworn I saw a shape, distinct and blue, very clear and small, further off than any hill the chart recorded. The chart was against me, my companions were against me, I never saw it again. On a day like that, height goes to one’s head. Perhaps it was the lost Atlantis focused for a moment out of time.

The streams that fall over the edges of the plateau are clear – Avon indeed has become a by-word for clarity: gazing into its depths, one loses all sense of time, like the monk in the old story who listened to the blackbird.

Water of A’n, ye rin sae clear,

’Twad beguile a man of a

hundred year.

Its waters are white, of a clearness so absolute that there is no image for them. Naked birches in April, lighted after heavy rain by the sun, might suggest their brilliance. Yet this is too sensational. The whiteness of these waters is simple. They are elemental transparency. Like roundness, or silence, their quality is natural, but is found so seldom in its absolute state that when we do so find it we are astonished.

The young Dee, as it flows out of the Garbh Choire and joins the water from the Lairig Pools, has the same astounding transparency. Water so clear cannot be imagined, but must be seen. One must go back, and back again, to look at it, for in the interval memory refuses to re-create its brightness. This is one of the reasons why the high plateau where these streams begin, the streams themselves, their cataracts and rocky beds, the corries, the whole wild enchantment, like a work of art is perpetually new when one returns to it. The mind cannot carry away all that it has to give, nor does it always believe possible what it has carried away.

From The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd, first published in 1977 by Aberdeen University Press. Copyright Nan Shepherd.

This story originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of AnOther Magazine which is on sale internationally now.