With The Virgin Suicides and Drop Dead Gorgeous, Kirsten Dunst came of age via two very different films that, together, revealed a new darkness in the American (teenage) dream

Girlhood Studies: How has visual culture shaped ideas of girlhood? In a new column for AnOthermag.com, Dazed’s editor Claire Marie Healy considers overlooked moments of coming-of-age on screen.

I recently discovered two videos of Kirsten Dunst on YouTube which keep playing like a double bill in my mind. The first is from 1995, when the then 13-year-old actress appeared on David Letterman to promote Jumanji. There, in a faintly creepy exchange, she babbles confidently to the host about this and that, such as the time she kissed Brad Pitt in Interview with the Vampire (she was 11), before doing a cheerleading dance in his honour. In the second video, it’s 2000, and the now 17-year-old Dunst is still fielding questions about kissing her co-star, this time with regards to Josh Hartnett, at the premiere of The Virgin Suicides. Here, in a low-cut red dress (“Cynthia Rowley made it special for me!”), she feels like the same 13-year-old girl, only with a few more layers of inscrutability: she is at once more exposed, in her slinky outfit and make-up, and more concealed. Child-Kirsten is overwhelmingly excited to be on television; when teen-Kirsten smiles, she’s self-conscious, her famously crooked smile pulled on like a mask. Her grin has a sense of effort. Is she thinking about who might be looking?

The weird thing about the way we watch girls grow up onscreen is that we feel a right to intimacy with them, and a hyper-awareness of their every bodily development – like a mother, or a sister. It also feels as though if movie-makers can keep them stuck in a certain time and place, and at a certain age, then we can too.

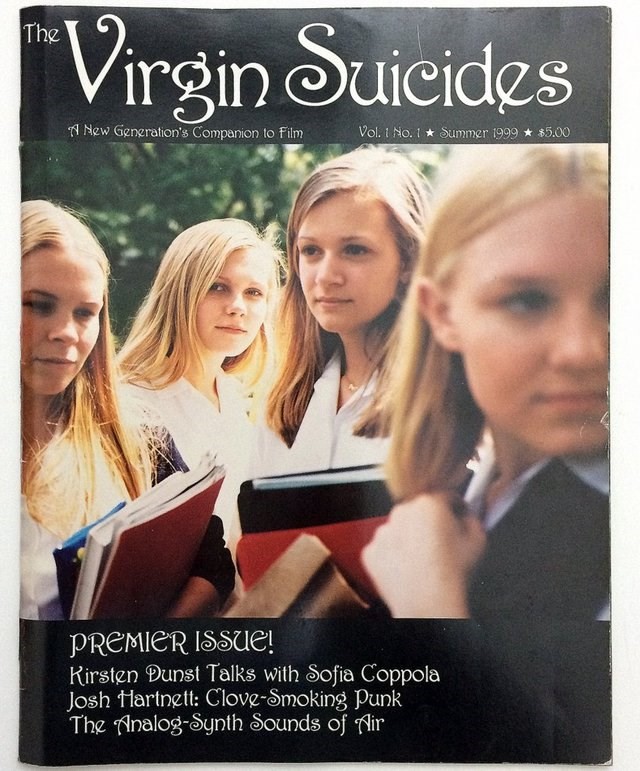

For Dunst, that time and place is 1999. The year was a gold rush for teen movies: not only Drop Dead Gorgeous and The Virgin Suicides, which she starred in, but also Cruel Intentions, She’s All That, 10 Things I Hate About You, Never Been Kissed, Election, Jawbreaker, American Pie. This was the year that Kirsten Dunst came of age on screen. “Virgin Suicides is a transitional film for me,” Dunst describes to her big-sister figure Sofia Coppola in the magazine produced to promote the film, now an IDEA collectors item, which you can peek at scans of online. “You have to be really careful with the movies that you do because as soon as you do a stupid movie then no one wants you for good movies. Especially now that I’m 16 and going into that category where I have to do older parts.”

Shot one after the other, Drop Dead Gorgeous and The Virgin Suicides initially seem like they were made on different planets. But rewatching them recently, it struck me how Dunst is doing similar things in both of them. Like a remedy for the glut of generic teen movies at that time, both projects brought a new darkness to how teenagers were presented on screen; Dunst’s turn-of-the-millenium work remains brilliantly defining for representations of girlhood that feel complex.

The Virgin Suicides, an adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel, stars Dunst as Lux Lisbon, one of five troubled sisters from a sheltered Catholic family in the 1970s Michigan suburbs, who are adored and obsessed over by a group of neighbourhood boys. The boys narrate the story, and for the viewer too, the story of the girls is one to be gazed at from the outside, with limited visibility. When Coppola shows Lux smiling or laughing, we respond like one of them, with awe. The camera always zones in on Dunst’s body parts in this peekaboo way: her toes caressing a male guest’s foot under the dinner table, the knickers under her sackdress with her boyfriend Trip Fontaine’s name written with a felt-tip pen. “I think when I first watched it, I was 13, and expected that by my millionth rewatch, I’d finally feel like a Lisbon sister,” Tavi Gevinson told me once of the movie’s strange outsider’s perspective. “Of course, I never did, because I worshipped them instead of relating to them. I experienced it as one of the boys.”

In Drop Dead Gorgeous, in which students compete in a local ‘American Teen Princess’ pageant, we are similarly placed at a distance from Dunst and a host of teen actress co-stars (Amy Adams, Brittany Murphy). But instead, the neighbourhood boys here become a group of men filming a documentary. Within this mockumentary framing, we witness resident school bitch Becky Leeman (Denise Richards) battle it out with our heroine, Amber Atkins (Dunst), with murderous consequences. (For a sense of the film’s bleakly comic tone, there’s no better image than Amber’s mother, who spends much of the movie with a beer can perma-fused to the flesh of her hand after a fire burns down their trailer.) The film is worth a revisit for Dunst alone, whose character tap dances, works at a mortuary and generally wins the day, smiling all the while. Like Lux Lisbon, Amber is judged on the basis of her beauty by a host of observers, and she puts herself there; she craves an audience.

The child star who made it to the other side, Dunst will always remain a teenager from a certain angle. For me, that’s because her performances in these films feel anticipatory: she perfected a new way of performing girlhood on screen, one that felt closer to a teenage girl’s real multiplicities. The roles that allowed her to do this were The Virgin Suicides and Drop Dead Gorgeous. In both instances, she seems to understand the way in which what a girl presents to the world is very different to what she feels: always keeping the truth just under that smile, and possessing a certain inscrutability. As academic Anna Backman Rogers told Dazed recently, “Coppola’s films are deconstructing the ways in which women are turned into surface, turned into image. Which is precisely why her fascination with surface and superficiality is not superficial, in any sense of the word.” Dunst, in her movie choices, holds the same fascination: just look at her later roles, like Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, or Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia, where her protagonists lead similarly double lives.

“In the end it didn’t matter how old they were, or even that they were girls,” says one of the boy narrators in The Virgin Suicides – but of course it does, hugely. These very different films both explore how teenage girls are always on display and observed. Both incorporate dead teenage bodies as an extreme symbol of what happens when the pressure of attention – of being under observation – reaches its pressure point. Both have been criticised for their superficiality. And both are centred by Kirsten Dunst who, in 1999, knew instinctively that to be a teenage girl is always a kind of performance; that’s why she plays the surface so well.