From Miu Miu to Madeline’s Madeline, cats are always a teen girl’s spirit animal – but what does the association tell us about our cultural fear of girlhood?

Girlhood Studies: How has visual culture shaped ideas of girlhood? In a new column for AnOthermag.com, Dazed’s editor Claire Marie Healy considers overlooked moments of coming-of-age on screen.

First you hear purring, then you see a nurse. “The emotions you are having are not your own,” the nurse says. “They are someone else’s. You are not the cat. You are inside the cat.” These are the opening lines of Madeline’s Madeline, which is finally out this month. You see a cat, then you see a girl who is a cat.

Or at least she is behaving like one. Helena Howard, playing the titular teenaged heroine Madeline, comes into the room on all fours and stretches out on her side, lazily. She makes noises; noises that quake and groan somewhere under her skin. She allows her belly to be affectionately rubbed by another woman who turns out to be her mother (Miranda July). She purrs with pleasure. Licks and nuzzles. Later, she hisses angrily, her eyes flashing.

The opening of Madeline’s Madeline is one of the great, strange expressions of adolescent angst in film. But it’s not a unique moment in cinema. Once you start looking, girls and cats have always been linked in visual culture. The four-legged creatures and femininity have gone together since ancient times: in the Middle Ages, they were known as ‘familiars’ of witches, as well as one form into which sorceresses could transform. For a modern-day small screen equivalent, see the Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, the Netflix reboot of the beloved 90s show, in which Kiernan Shipka’s heroine has Salem, a black cat, as her companion and protector.

When Miuccia Prada sent caped and camouflaged goth chicks down Miu Miu’s A/W19 runway in February, they were watched over by a black cat with a similarly witchy spirit. The cat, one of the stars of Sharna Osborne’s nostalgic multimedia set design, was par for the course at Miu Miu – which, after all, sounds feline in a different accent. The label has featured a lion’s share of cat imagery over the years, from the instantly iconic kitten print of S/S10, to a recent jumper featuring Snowball II from The Simpsons. But Osborne’s cat – cuteness overload laced with X-Files atmosphere – summarised the antithetical characteristics that the creatures possess the best. Cute, but psycho.

When it came to Madeline’s Madeline, director Josephine Decker felt the cat was Madeline’s spirit animal without a doubt. Detailing a summer in the life of a teenage actress, and her relationships with her mother and manipulative theatre director Evangeline (Molly Parker), the film is about frustrated female family dynamics, mental illness, but also a prolonged coming-of-age moment. It is, in part at least, based on Howard’s own experiences. One among many improvised characters the character has to inhabit as part of her experimental theatre rehearsals, Madeline-as-cat is accompanied by Madeline-as-pig, and, in a brilliant scene, Madeline-as-sea-turtle. “The pig, I always felt, was this side of Madeline that was dangerous to her somehow. And the cat was an empowering side of her,” Decker has said. “There is a way that cats can slither into and out of situations that I felt like Madeline also could do. In a way that was like one of her superpowers. Cats can enter a room and you’re like, how did you get here?” (And the turtle? “I dunno, I was just really into turtles.”)

Madeline, like a cat, can be manipulative, mischievous, loving, wild, and, finally, unreachable. Her character, suffering from erratic moods, struggles to pin down the right personality for the right moment. In one scene, where she goes to a barbecue at Evangeline’s house, her spontaneous one woman cat-play for the family group both magnetises and repels; as an audience member, you feel tense, wondering what will happen next (sure enough, within minutes, she inappropriately flirts with Evangeline’s husband, bending over for him the same way her body stretched out as the cat). For Decker, cats contain multitudes, which speak to the behaviour of a teenager who refuses to play by adult – AKA “human” – social rules. “There was something really manipulative and mischievous about being a cat, but also sensual and liberated,” Decker described in another interview. “They just felt like Madeline’s hero animals so deeply, they’re just like her.” Madeline’s refusal of the rules, her feline lawlessness, is ultimately her power.

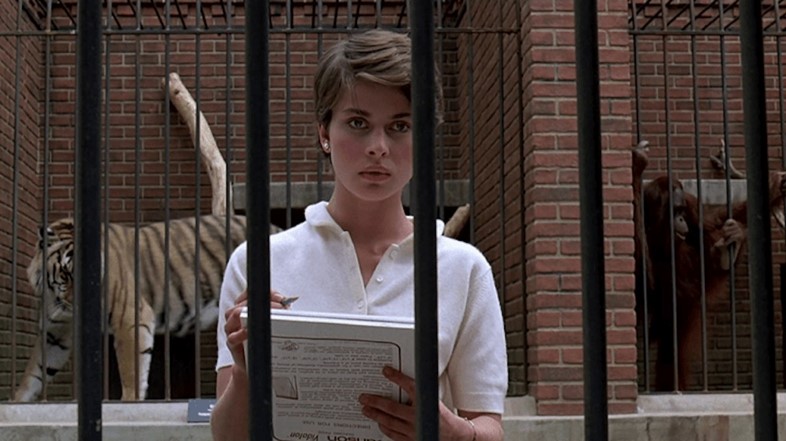

Decker coyly nods at the connection between cats and teen girl sensuality/sexuality in a way that other (it has to be said, usually male) directors put centre stage. In Dogtooth, Yorgos Lanthimos’ debut Greek-language film, two daughters and a son are suspended in a permanently childlike state by their parents, who keep them locked up in their gated house and teach them the incorrect meanings for different objects and animals, and that to leave the house is certain death. In this surreal, sun-bleached domestic prison, a cat, for instance, becomes “the most dangerous animal there is”, a creature who can attack, kill and devour a human with ease. But when a female visitor brings sexual games into the home, her targeting of the eldest daughter for sexual favours leads to strange power-plays: cat-like licking, with all its connotations, becomes an absurd part of the inter-familial relationships and a stand-in for the girls’ sexual repression. Anticipating The Lobster and The Favourite, Lanthimos’ camera trains on these sexual encounters with all the indifference of documentary: he just watches, and lets it happen. In Cat People (1982), Paul Schrader’s David Bowie-soundtracked psychosexual drama, the central character of Irena (Nastassja Kinski) is similarly childlike and naive, reuniting with her estranged brother in New Orleans with little experience of the world and love. Much like in the 1940s original, however, she possesses a dark secret: she is part of an ancient race who, descended from big cats, will turn into a black panther whenever she reaches orgasm with a partner. The premise isn’t exactly subtle but, as centred on Irena’s sexual awakening, it is a useful, if uncomfortable, comment on how young girls’ sexuality is seen as culturally threatening: as something that not even the girls themselves can control.

For Chloë Sevigny, herself a Miu Miu muse, cats and girls, with all their charged symbolism, were the natural subject for her first directorial effort. Kitty, her short film which debuted as part of the fashion house’s Women’s Tales in 2016, tells the story of a little girl on the verge of growing up: into a cat. “When I was really young I thought all cats were girls and all dogs were boys,” Sevigny told Dazed at the time. “I had this very feminine, feline energy from cats. I’ve definitely come across some cats where I believed other people that I knew were possibly reincarnated in these cats.” Sevigny’s image of the young actress with a dusky pink nose and whiskers made me think of Wanda Wulz’s cat-photographs: the leading early 20th-century futurist’s spooky double exposures, that make you wonder whether those piercing eyes are a girl’s, or a cat’s, or both.

As the philosopher Sarah Kofman notes in her writing on Balthus (another artist-obsessive of girls and cats), ‘cat’ comes from ‘cattere’ – to see, to observe. Like Sharna Osborne’s cat that watched over the girl-models at Miu Miu, we associate cats with what they see as much as what they do. They seem to contemplate us, to know something we don’t – maybe that’s why Ancient Egyptians held them aloft as all-knowing deities. When it comes to expressions of girlhood on screen, this is something Josephine Decker must understand when she turns Madeline into a cat. In the film, we often see the world through Madeline’s eyes, and the cat becomes an important tool for expressing the nature of that gaze. It’s a viewpoint that allows us to experience, on-screen, the subjectivity of frustrated girlhood – daughterhood, teenhood – in ways you never could in purely human terms.

That’s why, more than just a window onto girlhood, the cat is a window out of girlhood: the audience, too, peers out of Madeline’s cat’s-eyes, creating, as Simran Hans wrote at SSENSE, “a sticky, feline subjectivity” through an embodied, smeary lens. It’s an empathetic method for showing Madeline’s most cat-like characteristic: her devastating solitariness. “Cats have this ease and poise, but can also be really terrified and terrifying and neurotic, and it can be really hard to develop intimacy with them,” Decker has described. “I think that’s something about her character, that she’s not close to anyone really.” When it comes to the alienation that poor teenage mental health can produce, a cat’s eye view might feel more radically honest than a human’s. Remember: you are not the cat. You are inside the cat.

Madeline’s Madeline is out in UK cinemas and via MUBI now.