Plenty of films feature smoking teens, but the summer romance of A Swedish Love Story is the hardest habit to kick, writes Claire Marie Healy in the latest instalment of her AnOthermag.com column, Girlhood Studies

Girlhood Studies: How has visual culture shaped ideas of girlhood? In a new column for AnOthermag.com, Dazed’s editor Claire Marie Healy considers overlooked moments of coming-of-age on screen.

After rewatching A Swedish Love Story (1970) this summer, I started wearing my hair in a high ponytail again. The protagonist, Annika, is a 13-year-old girl, but I liked the way she furiously brushes her hair in front of her parents’ bathroom mirror, only to immediately tie it up, and the strands that eventually fall down over her eyes during the scenes that follow. I also made a mental note of her small leather jacket, that zips frontways, with pockets she shoves her hands into as she walks. She also smokes, constantly.

I didn’t take up smoking after watching this perfect film, but I was definitely tempted. A Swedish Love Story is a deeply felt love letter to teenage romance, but also to chain-smoking. All the adolescents in the film – especially Pär and Annika, whose relationship is the story’s focus – light up like they’ve grown a sixth digit. The thing is, so do the adults. By the second watch, you might wonder whether you identify more with the troubled parents than the teenagers, an experience which, for me, is why the film’s dual worlds resonate so powerfully.

Directed by Roy Andersson, the film details the summer slow-burn of Pär and Annika, two teenagers of different social backgrounds who have a chance encounter with one another at the film’s opening. Pär runs with a self-consciously rebellious crowd who, as a teenage motorcycle gang, could easily be contenders for Lisa Simpson’s ‘Non Threatening Boys Magazine’. But he eventually wins Annika’s heart, after a few of the usual bumps in the road. Tender young romances despite class differences are an often-seen trope – Arthur Hillier’s Love Story, starring Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal, came out the same year – but Andersson’s burns brightest, probably due to the naturalistic performances of its central duo, who actually look the age of the characters they play. They barely say a word throughout, but their glances, kisses with chewing gum still in, the way he puts his hand on the nape of her neck, feel like enough. Sometimes, it’s like the puffs of smoke have literally replaced the script.

The category of teenager was created, in part, by its representation in movies. The birth of the on-screen teen, as epitomised by James Dean’s short-lived incarnation of adolescent angst in films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955), practically synchronised with its invention in the popular imagination. That’s why the conjuring of teenage behaviour in cinema has always been associated with rebellion: gangs, motorcycles, and of course smoking. Like Taiwanese director Edward Yang’s 60s-set A Brighter Summer Day (1991), A Swedish Love Story speaks to the way global youth groups emulate the insubordination and tragic love stories they’ve seen in American movies and pop culture, no matter where they are from.

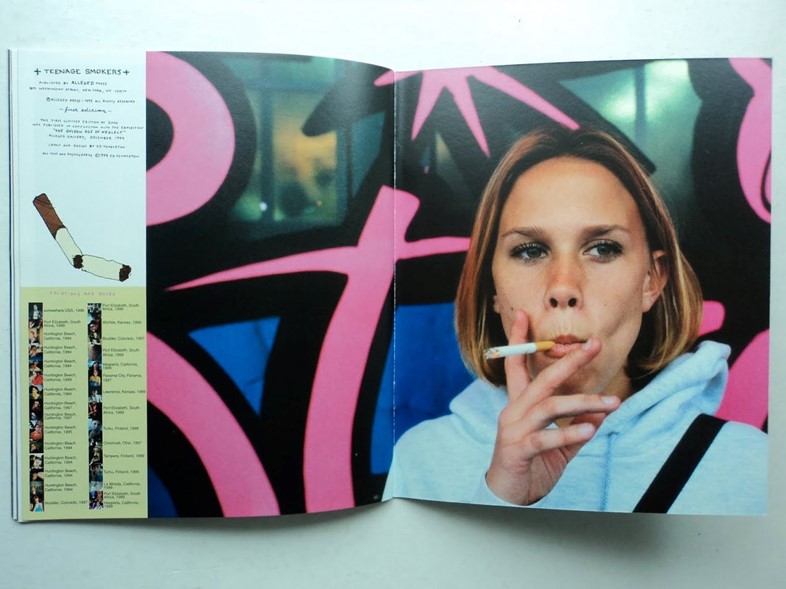

The connection between smoking in films, and actual teenagers smoking, is also fairly undeniable. According to a 2011 study of 5,000 15-year-olds, “teenagers who watch films showing actors smoking are more likely to take it up”. It’s this kind of research that means the debate still lumbers on as to whether films featuring smoking should actually be reclassified as 18s. One of the most successful anti-smoking campaigns in history actually used the power of movies, and their idea of rebellion, to convince teenagers not to smoke: from 1998 to 2003, the provocative “truth” campaign in Florida teamed up with local government, advertising execs and actual teenagers to create TV spots. Some adverts handed video cameras over to youths, to record themselves playing pranks against tobacco companies. The work of skateboarder-turned-photographer Ed Templeton, whose encounters with young smokers led to his seminal series Teenage Smokers, offers documentary proof of the problem in the era – while, ironically, contributing the kind of fashionable imagery that has always made smoking really cool. He’s also actually never smoked. “They are the ones who wanted to look cool so badly that they overcame the pain of starting smoking,” he has said of why he finds teenage smokers so fascinating. “They also overcame the logic of why it’s a bad idea.”

Even director Carol Morley, who has called A Swedish Love Story one of the number one inspirations behind her school hysteria drama The Falling (2015), admits she decided not to have the teenage girls smoke due to her prior involvement with an anti-tobacco charity. “I decided in The Falling to only have the older people smoking, so smoking is kind of old hat and anachronistic,” she told the BFI. “But A Swedish Love Story has the youngsters smoking all over the place, and renders the feeling and awkwardness of youth... populated with baffling adult behaviour, beautifully.”

As Morley notes, the adults of Andersson’s film are a hot mess, and it’s their contrast with Pär and Annika that makes the romance such a magnetic force in the film (despite the lack of plot action). The depiction of Annika’s parents – their marriage crumbling due to the evident manic depression of her white-collar salesman father – is in turns heartbreaking and darkly funny. What’s more, the events of the film find an echo in real life: the director, Andersson, fell into a deep depression after the success of A Swedish Love Story. Obsessive about not being labelled as a crowd-pleaser, he cancelled his next project, releasing the major flop Giliap in 1975 and then taking a 25 year break from film directing altogether. His 2000 release, Songs from the Second Floor, was a critical return to form – but in the intervening years, it’s fascinating how he seems to have turned towards the sphere of the adults, and all their dark thoughts: losing the wonder at life he must have felt once, in order to invest the romance of his teenage hero and heroine with such deep feeling.

Today, teenage smoking is as fleeting as most teenage romances. Only three per cent of teenagers in the UK smoke regularly today. Still, A Swedish Love Story made me want to spend my summer riding on the back of a boy’s moped, playing pinball, smoking cigarettes, or all of those things at once. If there’s one moment that makes risking your lungs by watching this film worth it, it’s when Annika shouts after Pär through a fence after a falling out, her big eyes filled with tears. Her snotty, heart-wrenching scream is an absolute gut-punch, a magic moment of cinema; and when he comes back to her, he’s riding his moped and – yes – smoking a cigarette.